Review of Maria Hill's book, Diggers and Greeks

Digging up truths behind Anzacs in Greece

Author: By The Canberra Times

Publisher: The Canberra Times

Publication: The Canberra Times , Page 14 (Sat 10 Apr 2010)

Keywords: Greece (6)

Edition: PA

by Dr Michael McKernan

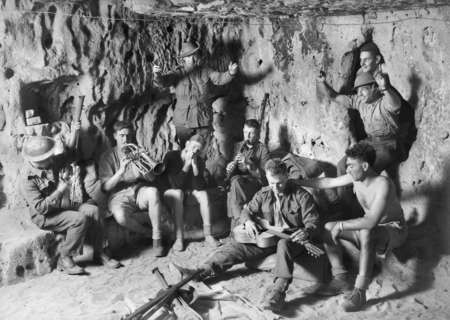

Photograph: March 1941. In the rocky tombs and catacombs of the Ancient Greeks, men of the Australia Infantry Forces (AIF) tune their instruments before performing a classic Greek dance with hands held high. (AWM 006325). Pp's 296-297, Maria Hill's, Diggers and Greeks

Australia Remembers 1995 commemorated the 50th anniversary of the end of the Second World War, in part, by taking Australian veterans to the places where they had fought. One ''pilgrimage'', as the organisers like to call these tours, took in North Africa, Greece, Crete, London and Paris. I rather wish Maria Hill had been with us on this trip.

She would have had plenty to say because the major themes in her book echo precisely what the ''pilgrims'' discovered in 1995. We only spent a day and a bit in Athens and went nowhere near the battlefields, such as they were, of continental Greece. Hill would nod in agreement but with some annoyance.

She argues that we simply do not want to know the detail of what happened in Greece. The ''Grecian Greyhounds'', Lord Haw-Haw called the retreating Australians of 1941. Through British duplicity Australian and New Zealand troops had been hastily and wastefully dumped in the north of the country immediately to fight a retirement to the south.

The Australian fighting in Greece is largely unknown now, and was hardly examined then. The retreat was inglorious and it seems those organising Australian memories in 1995 simply wanted to forget it. Hill has written this book in the earnest hope that all Australians will want to know more.

We spent marginally more time in the pilgrimage on Crete and looked at some of the places where the Australians did indeed fight. Hill is scathing about the lack of planning in setting up these major battles on Crete and quotes many sources, soldiers and war correspondents, who could see the hopelessness of what was attempted at the time. She argues convincingly that more aggressive and wiser leadership might have given the invading Germans a tougher time of it but asks, sensibly, how to account for the failure of the Allied high command.

Yet if the Germans had been held up on Crete, or even beaten there, would that have made much difference at all to the war's progression? Hardly. Crete was a small, largely barren island of little, if any, strategic significance. Most who have looked at Crete have agreed that the Anzacs should not have been there in the first place.

Hill writes shrewd, judgmental military history with clarity and insight. She skips along at an energetic pace and it is hard to contest her underlining contempt for those who moved the Australians from near victory on the North African desert to complete defeat in continental Greece and Crete. Her book is worth reading for that alone.

But as Hill tells us, ''this is a book about Australian soldiers and their Greek allies ... it is about human relationships and why they matter.'' Perhaps only a Greek- Australian could have written this book with its keen understanding of the inter- reactions between the two peoples.

The travelling veterans of 1995, and those supporting them, experienced the warmth of the love and regard of Greeks for Australians that Hill writes about with such certainty. The veterans were welcomed and heartily embraced by a Greek people who clearly still held Australian soldiers in the highest regard. The strength of the welcome for them on Crete was at least as great, if not greater, than that given by any other community on any other pilgrimage on which I travelled.

Those days on Crete were a deeply moving revelation, as is this book. The Australians were moved by the appalling poverty and suffering of the Greeks who nevertheless opened their hearts and homes to these soldiers from so far away. With little more than sign language as a means of communication, both groups seem to have understood one another.

A junior Australian officer who had studied classical Greek at school could read all the road signs and shop hoardings but when it came to conversation he was lost. Why the two groups worked so well together is a question Hill can only tentatively answer. That each side recognised the other as a genuine pack of ''mad bastards'' might be a starting point.

The travelling ''pilgrims'' in 1995 were taken to the Prevelli monastery on the southern side of Crete, a place from which many Australians were helped to evacuate. The monks were warmly hospitable and delighted in showing off their treasures. The ''pilgrims'' were quietly appreciative.

Then it was time for a glass or two of fiery liqueur on the monastic terrace and some equally strong and pungent cheese. One of the monks, unseen by us, produced a pistol from within the folds of his habit and fired a couple of shots into the air to show that he was happy. The noise, at such close quarters, was fearsome.

The shock, profound. But within seconds everyone, Cretan and Australian, was roaring with laughter. Mad bastards. People who understood one another. Diggers and Greeks is a serious and accessible addition to Australian military history about a campaign that has been unfairly overlooked.

It is a wise, loving and important book from an author passionately engaged with her subject. It can tell you a great deal about Australians and Greeks and a great deal too about the horrors of war and awfulness of those who direct them. Michael McKernan has written the introduction to The Gallipoli Letter, just published.

Headline: Digging up truths behind Anzacs in Greece

Author: By The Canberra Times