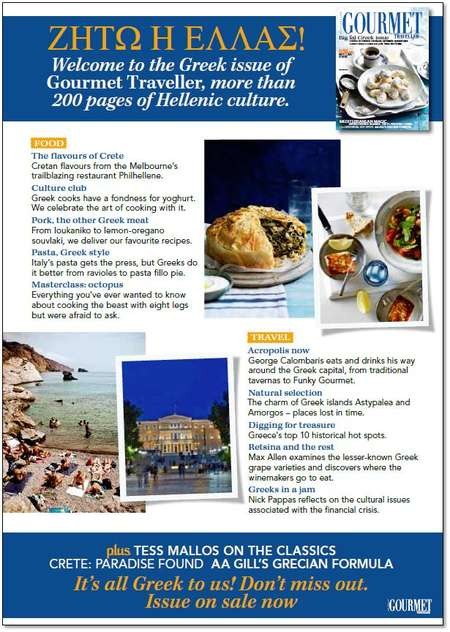

The Flavours of Crete, and other articles on Cretan and Grecian food

Author: Gourmet Traveller Magazine

When Published: October 2011

Publisher: Australian Consolidated Press Magazines]

Available: All Newsagents and Supermarkets in Australia

Description: Glossy, monthly magazine

October edition of Gourmet Traveller, available in Newsagents and Supermarkets, throughout Australia.

*Read also Kytherian Tess Mallos's article on the classics

A follow up to the March 2010 edition on Greek cuisine.

Crete, Greece

The island of milk and honey Crete, with its distinctive flavours and renewed respect for tradition, is at the epicentre of Greece’s agro-tourism revolution. Victoria Kyriakopoulos explores the island responsible for rekindling the love affair between the Hellenes and their regional cuisines.

I was on a research trip for Lonely Planet when I first came across Alekos, a kafeneion in the tiny Cretan village of Armeni. Apart from needing a pit stop to plan my afternoon route, I was hungry, it was 3pm, and I’d heard about their rabbit stew.

A kafeneion is a traditional Greek coffee house, but those in rural villages occasionally serve food as well, and this unassuming stone-built place, 10km along the road heading south from Rethymno, came highly recommended.

It was empty but for a few older gents sipping coffee and watching soccer, so I sat at a shady table outside and unloaded my notebook, SLR and crumpled road map. There was no rabbit that day, but the strapping 30-something owner suggested I leave it to him to prepare an alternative. "How do you know about the rabbit?" he asked.

Armeni, population 550, rates a mention in guidebooks only because of the Late Minoan cemetery discovered in an oak forest nearby, where 200 tombs carved into the rock revealed a precious cache of antiquities. The odd thing about the find was that there was no evidence of a sizeable settlement close enough to account for such a large burial ground.

Alekos turned out to be similarly enigmatic, but the exciting find at the incongruously located taverna emerged from the kitchen: lamb tsigariasto; a delicately crumbed green capsicum stuffed with myzithra cheese; and a salad of rocket, rusks, tomatoes, cheese and olives dressed with balsamic vinegar and fine Cretan olive oil. Simple, rustic cooking at its best.

I shouldn’t have been surprised. In Crete, as on many Greek islands, the best and most authentic food is often found in hinterland villages far from major towns and beach resorts teeming with tourists. Alekos was one of many culinary highlights of my travels through Greece’s premier food destination.

But there was another surprise in store this day. Curiosity soon got the better of my host, Sifis Frangiadakis, and he plonked his frappé on my table and took a seat. “Who are you?”, he asked.

Making my way up a dirt road in the nearby hills the next morning with Frangiadakis and his young family, I reflected that there are times when you have to blow your cover, and an invitation to a koure, or sheep shearing – and the legendary feasts that ensue – was one of them. The agricultural calendar still dominates life in Crete, and harvests and traditional seasonal agricultural activities are social and cultural events. This is, after all, the island where one village holds an annual sheep blessing, actually herding them through the church.

We arrived in time for the spectacle of a thousand sheep arriving over the hill to be sheared by the deft local hands who had pitched in to help. As children played and women prepared salads and starters in a makeshift kitchen, a dozen quartered lambs were cooking around a giant flaming pit – a shepherd’s method called antikrista – while more meat was boiling in giant cauldrons for the traditional pilafi, rice cooked in stock. When the work was done, the food, wine and raki flowed well into the afternoon, along with the warm hospitality for which Cretans are renowned.

Cretan food has become all the rage in recent years, as Greece embraces its traditional regional cuisines. Cretan restaurants and food stores have opened in Athens, and across the island the village taverna has been making a comeback and boosting rural tourism.

Until Frangiadakis took over in 1994, the humble kafeneion that his grandfather established in 1932 served locals mezedes to accompany raki. Word of many mouths soon put Alekos on the food press radar, and it has earned a place among the country’s 20 top restaurants for traditional Greek food in the influential Athinorama restaurant awards.

The award, Frangiadakis says, vindicated his decision to branch out and go the slow food route, relying on the recipes of grandmothers and "every home cook", and the experiences of local women in the kitchen. "We were losing home cooking. At some stage we lost a lot of things – we lost our tradition and our culture with easy food, with souvlaki and pizza and steak," he says.

More than 2.5 million tourists flock to Crete each year, the majority being Europeans seeking sun, sea and sand holidays. Many traipse through the ruins of the oldest civilisation in Europe. Nature lovers trek through the island’s stunning gorges and along its hiking paths. But Greece’s largest and most diverse island also presents a veritable gourmet trail through some spectacular country, with dramatic mountain ranges, bucolic villages, fertile plateaus, and vineyards and olive groves that have been cultivated on the island since Minoan times. Alternative and sustainable tourism ventures have seen the establishment of mountain retreats and farm stays, village restorations, and activities focusing on local culinary traditions.

Food has long been an intrinsic part of Cretan culture, from harvesting the family olive groves and foraging for wild greens to gathering snails after rain. The traditional Cretan diet, one of the healthiest in the world, first came to international attention in the 1960s, when the famous Seven Countries Study found that men in Crete’s mountain villages had the lowest rates of heart disease and cancer of all the populations followed in the study, and lived the longest, a phenomenon largely attributed to a diet high in olive oil, vegetables, grains and legumes and low in meat.

With the arrival of tourism in the late 1960s and ’70s, many turned their back on the land, their culinary traditions and the agrarian way of life. There was still great food; it was just harder to find.

Superior seasonal local produce is the hallmark of Cretan cuisine. Locals in the know will point you to obscure tavernas where the tomatoes come from the owner’s garden, the wine, cheese and olive oil are homemade, the eggs are from the chooks out the back, and the meat is from local farmers. Seafood lovers will drive to remote fishing hamlets for fresh fish caught locally by the taverna owner (or his brother or cousin). The recent resurgence of traditional Cretan cooking has seen the emergence of trendy upscale contemporary Cretan cuisine and restaurant certification programs promoting Cretan food and produce.

A return to organic farming is gaining momentum, while the global trend towards provenance has thrown a lifeline to small-scale producers of traditional cheeses and other local products, from smoked pork and yoghurt to wild herbs and aromatic thyme honey. Greek-American chef and educator Nikki Rose has been extolling the virtues of Cretan cuisine and sustainable tourism on the island for 14 years, running seminars and tours for cooks, students, researchers and food lovers. Part of a small but growing push to preserve Crete’s culinary heritage and traditions, she runs the Crete’s Culinary Sanctuaries program and works with an informal network of organic farmers, small-scale producers, women’s cooperatives, tavernas, and people who still make their own cheese, honey, raki and woodfired bread. Rose often takes students into local homes for cooking demonstrations, but for the past three years, she’s enlisted innovative young chef Dimitris Mavrakis.

"I don’t think it’s wise only to have old grannies doing cooking demos," Rose says. “We have to support young people doing something interesting if we mean what we say about protecting and celebrating the cuisine. Dimitri is a professional chef, he has great knowledge of his traditions and he spins it with innovative ideas."

Trained in French and Italian cooking, 34-year-old Mavrakis worked his way through the kitchens of upscale Cretan resorts before opening his own restaurant, Kritamon (named after a local wild sea fennel), in Arhanes, the village where he grew up. Inspired by the "creative" neo-Greek cuisine movement, he went back to his culinary roots – talking to grandmothers and village women who cooked the traditional way, and swotting up on the Cretan diet – before adding a chef’s touch to rustic cooking. As a child, Mavrakis would go with his father to the mountains to collect wild herbs and greens, and he believes being close to the food source is fundamental to maintaining the essence of Cretan food.

"The thing with Cretan cuisine is that you have to have the correct ingredients – 70 per cent starts before you go into the kitchen. I go to the mountains to find my herbs, I go to the organic garden to get my vegetables, to the shepherd and to the farmer and to the fisherman to choose my ingredients," he explains.

Mavrakis produces his own olive oil, and most of the vegetables come from his father’s organic garden. "I am half farmer and half chef," he says. Salads come from a local organic grower, the wine is local, and cheese and specialties such as smoked pork are from the best small-scale producers in the region.

Only 14km from the capital, Heraklion, and a short drive from the beach, Arhanes is a vibrant, sprawling village, with lovingly restored stone buildings. The grand palace built by the Minoans was destroyed in 1450BC, but there is a small archaeological museum in town and there are several significant ancient sites nearby, including the world’s oldest wine press.

Often touted as a model of village redevelopment, Arhanes is lively enough to keep its youth, while improved roads make Heraklion an easy commute. Mavrakis wants Arhanes to become a gastronomy centre for the island. "In Arhanes, you can see all of this nature, the mountains, the olive trees, the vineyards. It’s like Tuscany."

Arhanes is also in the heart of one of Crete’s premier wine regions, where wine routes are being established to boost wine tourism. Cretan wine is slowly catching up with Greece’s wine renaissance, producing premium modern and boutique wines from local varieties.

Leading the push are new-generation boutique wineries such as Tamiolakis Estate, in a picturesque valley just above the village of Houdetsi, run by young Bordeaux-trained winemakers. Dimitris Mansolas and Maria Tamiolakis met at college in France and returned to apply their craft at the organic vineyard cultivated by Maria’s father, Minas. In 2004, they built an impressive state-of-the-art winery from local stone and began to cultivate more local varieties. The vineyard is now reviving almost-extinct indigenous varietals such as vidiano and moschato Spinas, with some fine results.

Similar stories can be found across the island. At the Astrikas Estate, on a dramatic hillside setting in the far west of the island, Yiorgos Dimitriadis is applying the same artisanal approach to olive oil, Crete’s liquid gold. One of the few single-estate olive oils in Greece, award-winning Biolea oil – made from hand-picked Koroneiki olives – is extra-virgin, organic, stone-milled, cold-pressed, and light (and good) enough to drink.

In the early 1990s, after 20 years in Canada, Dimitriadis returned to Crete, where the olive groves that had been in the family since the mid-18th century were forested and ruined. The olive mill had been destroyed in World War II, and his father had left to seek work in Athens, leaving his grandparents to tend to the trees.

Dimitriadis, 58, and his wife, Christine Lacroix, planted new trees, revived others that were hundreds of years old, gradually made the estate organic and went back to traditional "slow" production methods, building a unique state-of-the-art stone mill with the help of local university researchers. "Olive oil studies show that in the old times when they were crushing the olives and pressing them without adding anything, no water or anything, the health benefit was there. In the new centrifugal processes that they use today, they have to use water and all the anti-oxidants and vitamins are water soluble, so the water that you throw out is carrying a lot of the health benefits the oil should have.

"We took an old system and brought it up to today’s food production standards and now we are globally certified and produce the highest quality possible olive oil, and we can prove it with chemical analysis," says Dimitriadis, the fifth generation to produce oil at the estate. Since the first labelled oil came out in 1997, Biolea has gone from strength to strength, and now exports to US, Japan, Canada and northern Europe. The visitor-friendly estate, which has a tasting bar and a mezzanine level from which the production process can be observed, has been an important marketing tool. "Last year we got about 3500 visitors; this year we are going to get close to 10,000. We have major tour operators sending people from all over the world."

Dimitriadis never dreamt he would make a career from olive oil. The previous generation, he says, had made every sacrifice so that their children would get out of farming.

"This mentality is turning around and we see young people coming back who are educated and have a mission, and they go and take over what their father or uncle or grandfather left, and they are producing much better, more specialised products with an identity. "They make Cretan cheese, they are proud to produce Cretan wines and market them for what they are."

Dimitriadis’s daughter has spent this summer in Crete after finishing her studies abroad. "She is following me around to see if this is for her or not, so I am holding my breath to see if the next generation is going to do what I did. If they don’t, so be it," he says.

Southwest of Astrikas, early pioneers of Crete’s generational lifestyle change have put the remote mountain paradise of Milia firmly on the island’s foodie trail. A 2km dirt road leads to a superb taverna serving organic home-grown traditional food in the serenity of a once-abandoned 17th-century hamlet. Revived 18 years ago by two eco-minded locals with a back-to-basics philosophy, Milia minimises its environmental footprint in the 16 lovingly restored stone cottages, which have only basic solar power (the fridge uses the only power point). Their organic farm supplies most of the produce for the taverna, where many dishes are baked in the woodfired oven, along with bread made every day. They make their own oil and cheese, rear chickens, goats and sheep and procure local wine and produce.

Milia evokes the austerity and subsistence way of life from which Cretan cuisine was born. With Greece in the grip of an economic crisis, some see a silver lining for local cuisine. Not only are more people heading to the hills for honest, good-value, traditional cooking, but anyone with a patch of dirt is starting to plant their own vegetables.

People will rediscover the flavours of fresh food and the art of foraging for nature’s wild gifts, says an optimistic Mavrakis. "Many people don’t have money to go and buy meat and fish, so it is better to find snails and wild greens and cook what they can grow in the garden. I think in the end the crisis will be good for food."