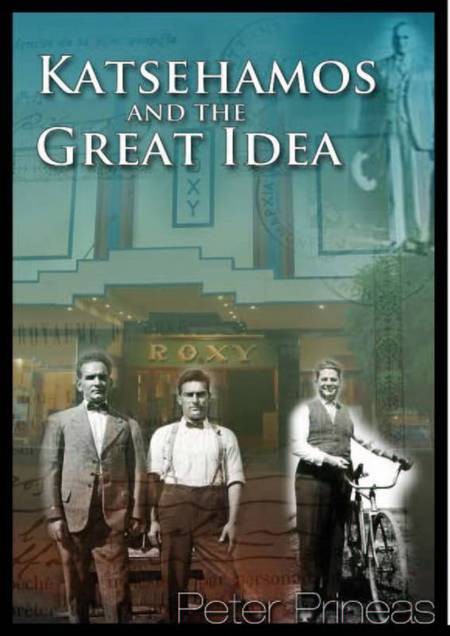

Katsehamos and the Great Idea

By

Peter Prineas

A Review

I have just read a book that fits neatly into that nexus where man meets history. Peter Prineas’ Katsehamos and the Great Idea tells a tale of struggle, courage, stoicism, doggedness and pride which is profoundly recognizable to the children of the Greek Diaspora, echoing in the secret part of our soul, to remind us of who we are; where we come from. It presents us with the spectacle, often poignant, always moving, about the young people who were forced out of Greece by historical imperatives beyond their control, into a stubborn and hostile world where they were expected to make their way minus language, minus marketable skills, minus opportunity.

But to think of this only as an account about Greeks for Greeks would be to miss the point. It is more than that; it taps into the experience of everybody who has had to up stakes and move somewhere else in order to make a life. It vibrates with the great migrations that arose out of the two World Wars, the chaos of South-East Asia, the redistribution and redefinition of power in Africa, endemic poverty and the ideological conflicts that continue to bedevil us today. Those who have been forced to migrate to a place not necessarily of their choosing or those who have had to move aside to accommodate them would find elements of this book hauntingly familiar.

History is most interesting when it affects the people you know; the people Prineas is talking about were particularly vulnerable to the effects of world events making it impossible for them to stay in Greece. In order to show their journey as they made their way to Australia via the United States and a war or two, he effortlessly evokes the smoky atmosphere of a kafenion in America full of men missing home and family, showing us his grandfather, Peter as a 16 year old, holding a cigarette in a work-hardened hand with the cocky assurance of a boy-man. Yet he remained a proud Greek and it is eminently believable that he was one of many who chose to go home to fight a battle that was long overdue. A confrontation imbued with the Great Idea.

Prineas begins with a person, a town, an island, three countries, a world at war, an emergent, fractious peace, another town on another continent in another hemisphere and the inevitable repercussions of decisions arrived at with no thought of the people who had to live by them and the choices they were forced to make. He tells an all too human story and at every stage, he touches base with the people who lived it, and whose actions, noble or ignoble, drove it forward.

In describing how his grandfather, Peter Feros, with partners Emanuel Aroney and George Psaltis, built the Roxy cinema in Bingara, Prineas tells the bigger story of emigration. Yet it remains a deeply personal family narrative with an emotional authenticity based on the fact that it is about real people; people he knew. This is a celebration of both his grandfather and all the men and women who took part in the early days of Greek migration. Here are the shades of the Aroney brothers and Barba Yiannis, all of whom had served in the Balkan Wars and of Mr. Hlentsos who couldn’t; of Spiro who carried his half-dead friend back from the Front; of Katina and Stamatina, who found themselves in foreign towns under a different sun; of Ioannis who became John in the space of a journey.

He exposes the exciting hidden histories of the countless owners of the countless cafes in the countless towns whose ordinariness belie the extraordinariness of their lives. Those of us whose family secrets resonate with these stories are ambushed by the sense of deja vu. And yet it remains quintessentially the story of the Feros family; their struggle, their tragedy, their triumph.

It is about the kind of vision that was prepared to take a punt on a promise, and build an edifice for a small town in not-quite-outback New South Wales that would have graced London, or Paris, or even New York and was repeated throughout Australia, bringing a little flamboyance, a bit of splendour and even some Americana to town.

However, there is another element in this book; Prineas introduces us to the Megali Idea, The Great Idea, the thought, hope, even ambition that a nascent Greece, newly released from centuries of oppression could reclaim that which it had lost; the great City itself, Constantinople. He shows that this was not as quixotic as it sounds and that its failure owed more to political expediency than to a sense of historical rightness.

He reveals the power of the Great Idea over the Greeks who believed in it, fought for it, and invested it in the destinies they were constructing in their own new world. These lovely, courtly, daring, clever, dreamers, of whom his grandfather was one, laid the foundation of a movement which has added interest and texture to our society.

Another motif in this story is the twin themes of racism and betrayal and you see how the prevailing attitudes permitted the development of a bitter sense of entitlement on the one hand and justification for bad faith on the other. There is very little to choose between the behaviour of local bureaucrats in the matter of planning permission for the cinema or the Great Powers when it came to deciding the fate of Greece. And yet you are heartened by the natural fairness that was displayed time and again on a personal level. Prineas tells his tale lucidly and objectively, endeavouring at every turn to give both sides of the argument. Although there is treachery and duplicity, there are no real villains here, just flawed individuals trying to do the best they can.

When I was reading it, it brought to mind a photo I have of a balding, tubby little man, sweeping the floor of his milk bar. A customer, Sue, from the exchange, a woman looking a bit like the popular notion of the appearance of an ancient Greek, you know, tall, blonde, blue-eyed, faces the camera. Tiny Norma, who worked there for… oh … ever, is just visible on the other side of the counter.

I love this photo because it tells a story as all good photos do, but it’s incomplete. There is no hint in it, for example, of a ship-board romance; no hiss of bullets in the dark and a chance, quickly seized, to escape through enemy lines; no mention of the gallantry of a sailor who couldn’t swim; no trace of a commitment to a Great Idea. It doesn’t show the adventure. No, you need a book for that, a book which will take the facts and the people who lived them and spin a tale that contains all the elements of a good yarn; conflict, excitement, romance, hope, tragedy, suspense, and a satisfactory ending.

This book is suffused by the Australian sunshine and pervaded by the eucalypt timelessness of the bush, but it reaches beyond that. We are all stakeholders here. Anyone who has had to overcome the feeling of alienation to fashion their own authentic role in a new story or to find a way to live their dream even if it means adapting it to different conditions, or who grew up in a country town, had a milkshake in a café, remembers rolling Jaffas down the aisle at the Roxy, has a place in it. Although it tells a specific story, it is in fact a story about us all, told sensitively, perceptively and scrupulously, and in letting us into the heart of a family, it also lets us into our own.

The book is available from the publisher,

Plateia Press,

32 Calder Road, Darlington, NSW,

or email here

phone (02) 9319 1513

and also from Gleebooks, 49 Glebe Point Road, Glebe NSW, 2037 and selected bookshops.

Katsehamos and the Great Idea is also available in the New England and Northwest region of NSW, from the Roxy Theatre, Maitland Street, Bingara.

Phone: 02 67240003, or

email here