Glass Plate Negatives. What are they? How do you clean, preserve, and archive them?

Information regarding glass plate negatives.

Views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Powerhouse Museum.

Information on the following websites will prove helpful. [Do not be concerned with minor disagreements regarding handling and treatment]:

www.preserveart.org/technicalleaflets/glass_plate_negative.htm

The Upper Midwest Conservation Association, UMCA Technical leaflet 'Cleaning glass Plate Negative's'.

http://www.archives.gov/preservation/storage/glass-plate-negatives.html

Preservation and Archives Professionals. How do I house glass plate negatives?

There was a very good reference which was located at:

http://slisweb.lis.wise.edu/~hamuir/678/glass.html 'Images on Glass: collodion Wet Plates and Gelatine Dry Plates'.

which appears to have been moved/lost.

This was prepared as part of the Preservation conservation course at the UW - Madison's School of Library and Information Studies.

In the interim go to UW's, Madison web-site at:

http://www.slis.wisc.edu/continueed/photoarchives.html

There you will find reference to following workshop:

"The recommended text for this workshop is the Society of American Archivists's (SAA) manual Administration of Photographic Collections, by Mary Lynn Ritzenthaler, et. al.; OR if available, the forthcoming SAA manual Photographs: Archival Care and Management [due out in 2006] by Mary Lynn Ritzenthaler and Diane Vogt-O'Connor, with contributions by Helena Zinkham, Kit Peterson, and Brett Carnell. (These publications can be purchased at SAA's website, http://archivists.org/)".

Each of these websites provides information about the two types of glass plate negative, the earlier collodion (cellulose nitrate) wet plate and the later dry plate. They give the dates for each.

You can also look at:

'Glass Negatives' Information sheet 5.3.10 copyright NMPFT 2000 National Museum of Photography Film and Television Bradford, West Yorkshire http://www.nmpft.org.uk

'Tech Talk - Glass Plate Negatives -Storage of glass plate Negatives, Robert Herskovitz Chief conservator, Minnesota Historical Society Minnesota history Interpreter. July 1999.

John Stathatos, of Potamos, Kythera, also recommends the following reference, which includes extensive illustrations and is useful in helping to distinguish collodion from dry plates:

http://aic.stanford.edu/jaic/articles/jaic30-01-005_4.html

There are glass plate sizes up to 18x22 inches (460x560mm), and probably larger, depending on the sizes of printing paper available. These tended to have a wider variety of sizes with collodion plates as these were prepared by the photographer. Later gelatin plates were factory prepared and sizes became more regular, related to popular camera formats.

In the 1860s, there were no enlargers, so all prints were contact prints, where the glass plate was laid face down on the photographic print paper; the print was therefore the actual size of the plate. With later gelatin plates, an enlarger could be used.

Common sizes

8.5 ins x 6.5 ins (called whole plate) =215x165mm

6.5 ins x 4.75 ins (called half-plate) =164x120mm

4.25 ins x 3.25 ins (called quarter-plate) =110x82mm =105x80mm

Modern sizes for sheet film, the successor to glass plates, included plate sizes plus:

Called 5 ins x 4 ins = 100x130mm approx

Called 10 ins x 8 ins = 200x255mm approx

I am fairly sure these sizes were also available in gelatin glass plates.

There in nothing special about the glass. Evenness and flatness were better with gelatin plates. When you find glass plates, the plain glass side is frequently much more dirty. The emulsion - ‘ image’ -side, as long as it has not been affected by mould or water, can be cleaned gently by blower brush / fine brush, as described.

If the glass, non emulsion side, needs cleaning, a mixture of distilled water with a little ethanol / methylated spirits and a little ammonia may be used on a soft damp cotton swab / cloth, as long as this is discarded when dirty. If the image is peeling off, this may not be possible. No free liquid may be used, as this may reach the emulsion edges.

The edges of the plate must be supported to stop the face-down emulsion contacting anything during this process. I do not recommend such cleaning without the advice of a professional conservator.

As the website text explains - ‘for storage’ - it is best to have the plate surfaces in contact with an acid free, neutral pH paper, made for this purpose. The simplest is a single fold, but this would also require an appropriate seamless slip sleeve of paper or polyester (or polypropylene). Similar sizes should be stored together, all vertically, resting on one edge, in an acid-free box.

The problem is, you would need to know the condition, sizes and numbers of negatives before you could be sure what materials to order for safe storage. Suppliers of museum and archival materials exist in Greece.

Ideally, relative humidity should be above 40% and cool, but with the same stable RH & temperature. Please read my (word document attachment)explanation of the International Standards Organisation (ISO) standards for long term storage of photographic materials.

See, AN EXPLANATION OF THE NEW ISO STANDARDS FOR LONG TERM STORAGE OF PHOTOGRAPHIC MATERIALS

James Elwing

Conservator, Archives,

Power House Museum, Sydney.

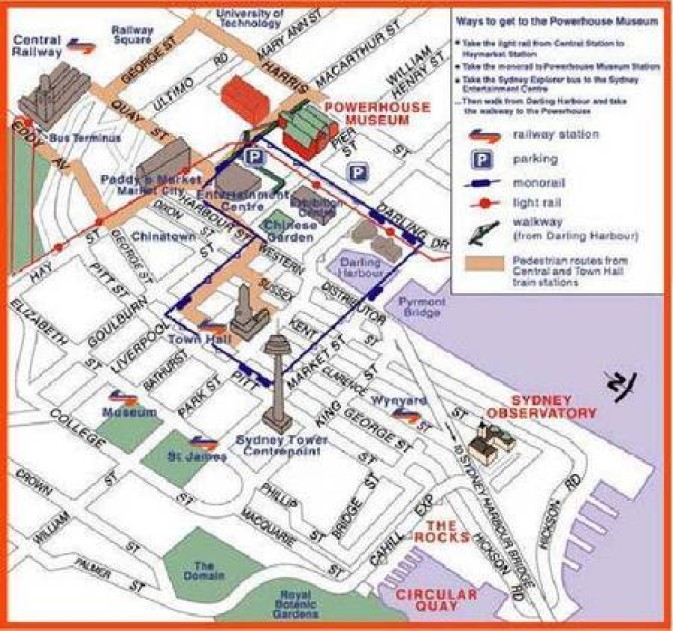

Top, Map of Sydney, indicating how to find the Power House Museum.

Address

500 Harris Street Ultimo, Sydney NSW 1238

Information Desk Ph: 9217 0111

How to get there

Entrance for 1 day study courses:

Entry via the schools entrance staircase - stairs leading down to this entrance are

located diagonally across from the Harris St courtyard. If you are walking through the covered walkway from Chinatown and the Monorail when you walk out into the Harris St courtyard the stairs are on your immediate right.

Public transport:

Bus: Buses travel from city locations - Circular Quay and Wynard to and from outer

suburbs along George St. Alight at the Harris St or Haymarket bus stop and from either it is a short walk of about 10 mins to the Powerhouse Museum.

For further information on bus and trains call the Sydney Transport Authority: 131 500