(01) Dimitrios Aronis-Beys: Departure from the Motherland

(An extract from the memoirs of Prof. Manuel J. Aroney)

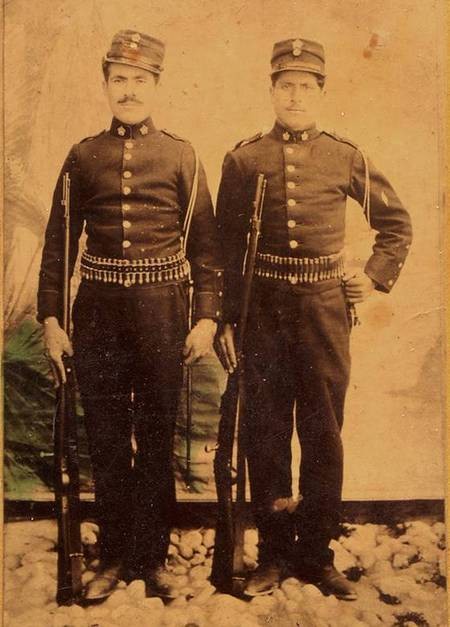

My father Dimitrios Aronis and colleague doing military service in the Gendarmerie in Greece. Photograph taken circa 1906 prior to Dimitrios leaving for Australia.

A sombre mood hung over the village of Aroniadika on the Greek island of Kythera as on this day in 1908 one of its favourite sons was leaving. Dimitrios Aronis, son of Emmanuel Aronis (Beys or Moustakas), was about to undertake a journey to far off Australia – the other end of the world. Goodbyes were said to those visiting the family home and to others congregated in the nearby village square, the Platia Tsiyoura, which served as a communal meeting place. Here lived memories of happy Summer night revelry, singing and dancing to the music of violin and lute but they in time would fade almost to obscurity.

A prayer at the Church of Ayios (Saint) Sotiras, candles lit for divine protection, then Dimitrios set out astride a donkey escorted by his closest relatives and friends, heading north along the dirt track that passed for the island’s main road. The group wended its way in the direction of the town of Potamos then beyond it to a staging post identified by an engraved bronze plaque as the “place of tears, joy and sorrow”. Dimitrios Aronis embraced and kissed his mother Garifalia in an emotional farewell and his other relatives, all members of the Aronis clan. His father Emmanuel Aronis had died the previous year. Many tears and anguish, since it was known that those undertaking this long journey rarely returned but, in the unlikely event that they did, the reunion would be one of great joy.

The place of tears, joy and sorrow – This monument was erected in 1908 to commemorate the place where families and friends farewelled those going abroad.

Photograph provided by Mr M. Sofios of Potamos.

Close up of the engraved bronze plaque commemorating “the place of tears, joy and sorrow”.

Photograph provided by Mr M. Sofios of Potamos.

A few hardy souls persevered beyond this point, pressing further north and negotiating the tortuous hilly and often precipitous pathway to the distant port of Ayia Pelayia. Dimitrios waited for the ship to Piraeus which, when it arrived, was forced to anchor some way offshore clear of the shallows. Final farewells said, he clambered onto the back of a hired boatman and was carried to a rowboat that would take him and a few others to the vessel waiting further out. He was leaving the land and the life so close to his heart and heading for the great unknown but within him lay the hope, so often expressed in later years, that one day he would return. Regrettably this was not to be.

Photographs depicting people departing Kythera from Agia Pelagia by rowboat to ships anchored offshore.

Photograph provided by Mr M. Sofios of Potamos.

It was goodbye to Kythera, immortalized in ancient chronicles as the island of the Goddess Aphrodite. From here, legend has it, Paris eloped with Helen of Troy precipitating the launch of a “thousand ships” and heralding the start of the Trojan War. The ship ploughed its way through waters steeped in history and mythology, crossing the straits to Cape Malea, the southern-most tip of the Peloponnisian peninsula and, not much later, the ancient Byzantine fortress of Monemvasia came into view. In twelve hours or so Dimitrios found himself in the port city of Piraeus and thereafter the capital Athens only a few miles inland.

Travelling to Australia in those days involved first crossing the Mediterranean Sea to Port Said or Alexandria in Egypt and waiting for an ocean-going ship bound for the southern continent. The journey on the Roon was long and arduous, terminating on the 17th of December 1908 in Sydney at the eastern edge of the vast island nation of Australia. Dimitrios was just twenty-three years old at the time. Like most of the inhabitants of Kythera he had very little schooling; the village of Aroniadika was in the northern part of the island in a relatively poor region and far distant from the capital Hora which was the centre of the educated, cultured and administrative class. His destiny, had he stayed, would have been to work the small land holdings owned by the family, tending olive groves, grape vines, almond trees, vegetable gardens. Add goats, sheep and sometimes fish caught in the waters off the island, and that was it – subsistence living at a low level. Further, the land of the north was generally barren and rocky, not good for agriculture and unable to sustain a large family no matter how intensively it was worked. Dimitrios was one of eleven children, the eldest of which was George followed in turn by Maria and Marouli (both of whom died young), Stamatia, Anthousa, Evgenia, Dimitrios, Minas, Panayiotis, Alexandra and Erofile. To augment his income, their father Emmanuel had a blacksmith’s shop in the neighbouring village of Friligianika and for much of the time he laboured there with his son Dimitrios.

Over the previous decades a number of villagers had left Aroniadika to seek work and a better life in Athens, Piraeus, Smyrna (in Asia Minor) and generally in countries bordering the Mediterranean and Black Seas. A few ventured further afield to North America and even as far as Australia. As it transpired, eight of the brothers and sisters would migrate to the USA or Australia; one of the sisters, Erofile, remained in Kythera with her mother.

Dimitrios was particularly drawn to Australia because it was known that others from Kythera had been able to establish businesses in Sydney - restaurants, oyster bars, fruit shops - and this type of work required very little knowledge of English. Newcomers were enticed with the promise of jobs by shop proprietors needing good hard workers who would tolerate harsh conditions without complaining and these could most easily be found by persuading others from the Kytherian villages to join them – a chain migration from the island. Dimitrios became a cook labouring in the kitchens of cafes, grilling steaks or fish, peeling potatoes, opening oysters, washing endless piles of plates, and so on. For five years he worked at the Harbour View Cafe at 5 Pitt Street Sydney and after that in various other Greek-owned shops in the city. The hours were long, the wages low, and it was essential to lead a frugal life – after all, money borrowed for the fare from Greece had to be repaid and financial support was needed by the family in Kythera. It didn’t help that he was a quiet soulful man who yearned for the warmth and love of his family but, like it or not, he had to come to terms with the hard life and solitude of this alien land.

Dimitrios, later to be my father, was never a hard-driving entrepreneurial type nor a self-promoter. Rather he was an easygoing peaceful man, well regarded by everyone, and a diligent conscientious worker. I remember him as such in later years of his life and these impressions have been confirmed by others who knew him as a young man. It was remarkable that in November 1996, while I was in Kythera, I met Mr Panayiotis Drakakis (also known as Ellinas) at his home in the village of Drimona and despite his ninety-eight years, he remembered my father well and told me that they were working together in 1913-14 at Petro Galanis’ cafe in Campbell Street in the Haymarket area of Sydney. My father was a cook while Mr Drakakis waited on tables. He went on to mention that my father’s brother Minas also worked in that cafe for a time; almost certainly he came to Australia with Dimitrios. Minas was dapper and had a characteristic physical defect – he had lost his right hand and part of the arm while throwing dynamite into the sea off Kythera in what was an effective but wasteful form of fishing, quite common in those days but later prohibited by law.

The Sydney of that era was vastly different to the large cosmopolitan city that it is today. Australia then was a very isolated insular country, a far-flung part of the mighty British Empire, and it was very parochial and Anglocentric. The few hundred Greeks of Sydney, in common with others scattered about the continent, were regarded as unwanted foreigners and accorded a lowly status in the social order. Their strange-sounding names were derided – long and difficult to pronounce. Dimitrios was too much to take so it became common practice for anyone with that name to be called Jim. Also surnames ending in “s” seemed wrong to English ears, so Aroney was imposed for Aronis. Thus my father emerged, in Anglo perception at least, as Jim Aroney.

The host community was virulently racist and anti-Greek attitudes were exacerbated by Greece’s neutrality in the early part of the first world war at a time when British and Australian troops were fighting the Germans and the Turks in Asia Minor and the Middle East. In December 1915 anti-Greek violence exploded in the main streets of central Sydney where mobs of drunken rioters, soldiers and civilians, smashed the windows of Greek shops causing serious damage to many premises. Greece was later to enter the war on the side of the British but the xenophobic attitudes of the Anglo-Australians left a bitter legacy in the minds of the Greek settlers and racial tensions were to persist for decades. Dimitrios decided to leave Australia to join his relatives in the USA and, departing late in 1916, he travelled to Boston to try out life in America.

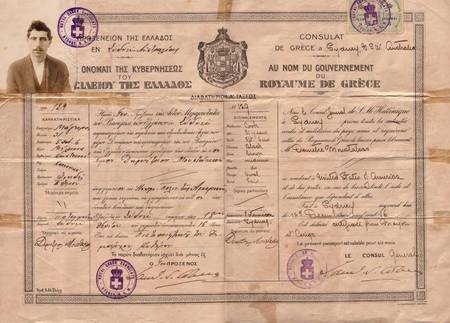

My father’s passport issued by the Greek Consulate of Sydney in 1916. This passport enabled him to travel from Australia to the USA.