Prof Manuel J Aroney: First trip to Kythera 1966

Extract from the memoirs of Prof Manuel J Aroney (Beys)

For Australian academics in the sciences, it is almost mandatory to go on study leave to prestige universities or research institutes in the United Kingdom, Western Europe or North America, to gain experience and reputation at international level and, hopefully, to impress a luminary or two who could provide valuable support in subsequent career moves

In 1965 I had been serving the University of Sydney as Lecturer and Senior Lecturer for more than the six years required to entitle me to a one-year period of sabbatical leave. Initially, I flirted with the idea of spending this time in some congenial part of the U.S.A. Thinking more about it, I began to wonder if the leave could provide an opportunity to see Greece – this had great emotional appeal. It would be an unusual course to take since Greece could be regarded as a logical destination for the archaeologist, historian, linguist or classicist, but it would be of little benefit for a scientist in my field of interest.

I mentioned this wild idea to Professor Le Fèvre, Head of the School of Chemistry, knowing that he was ecumenical in his attitudes and, unlike many others, would not dismiss it out of hand. He came up with the suggestion that I could arrange for the University of Athens to be my home base while on leave and from there to radiate out to other countries in Europe which had strong scientific institutions.

My wife Ann and I planned to be away about ten months and commenced our journey on the second of January 1966 when we boarded the Greek liner Ellinis. There was some apprehension as we knew the months ahead were not going to be easy with our sons, Jim only four years old and Theodore two, but it was comforting to have with us Aunt Evangelia and her daughter Nina who, having heard we were going to Greece, decided to come as well. The Ellinis was a clean, handsome ship, arguably the best of the Chandris Line, which was plying the England-Australia migrant route though it also took in the Greek port of Piraeus. The trip was wonderful; twenty-nine days of indolence and luxury with food, drink and entertainment and, importantly, warm sunny weather and calm seas.

In the ensuing five months we met many relatives: Ann and the children spent their time in a flat I rented at Pasalimani in Piraeus next door to her uncle John Calligeros and his family. In this period I gave lectures at Athens University and universities and other research centres in Israel, England and Germany.

My family with uncle Peter Aronis (my father’s brother) taken in Athens in early 1966 soon after we had met him.

When summer came, people were leaving in droves to escape the searing heat of Athens. I rented a car and took the family to some of the famous sites in and beyond Athens – the Acropolis, monument of Philopappos, the ancient Agora, Lycavittos Hill, the Roman theatre of Herodus Atticus, the National Archaeological Museum, Syntagma Square, Parliament House with its Evzone guards, the stadium nearby, the Royal Gardens, the delightful seascape stretching from Piraeus to Sounion; the list goes on. Of course the highlight was the Parthenon. We drove further afield to Delphi, Ossios Loukas, Corinth, Olympia, Mycenae and around the eastern part of the Peloponnisos – more places, more photos. We took boat trips to the nearby islands of Aegina and Hydra and, on a later occasion, to Rhodes

July was coming to an end and it was now time for the big one – Kythera. My expectations had been built up since childhood and with a sense of awe and reverence, I was now undertaking this pilgrimage “home”. Aunt Evangelia was anxious to see her late husband’s village, his childhood home; surely his spirit would be lingering there. Together with Evangelia and Nina, we all crammed into the car and drove to the wharf at Piraeus harbour where we were to board the ship Myrtidiotissa for the journey south to Kythera. We watched as the car, our belongings locked inside, was enmeshed in a net then winched up by crane in preparation for loading. With the car precariously high at about sixty feet, the crane was stopped while one of the wharf labourers came to me and said (in Greek) “What about some money to buy coffee for the boys?” I looked up at the car and with all the haste I could summon, thrust at him what must have been a generous amount. He signalled, and the car was swung over the side of the ship, gently lowered to the deck and secured. We went on board to seek out the cabins we had booked in preparing for a trip we knew would take about twelve hours, providing everything went to plan. It was a morning departure and we were in luck – conditions were ideal for the voyage. I positioned myself on the bow and stared at the sea around while my imagination ran riot with images of ancient mariners, mythological heroes, great figures of history, who had negotiated these same waters centuries and millennia before. Kythera came into view – a dark, elongated stretch of rock rising out of the sea; it was worlds apart from the romanticised scene depicted in Jean Antoine Watteau’s famous painting Embarkation for Cythera, which I had seen in the Louvre.

We berthed at Ayia Pelayia, the northern port for the island, and bedlam prevailed as crowds of people swarmed around the newcomers, luggage was carted out, cars unloaded; traffic snarls in the constricted area. Aunt Kerani was waiting there for us and with some help from the locals, we were soon on our way as part of a convoy of cars heading up the hill to a plateau and then south along the main traffic route. On reaching Aroniadika, we branched off to the left and within five minutes were in the village of Aloizianika which was built along the crest of a high ridge. Night had fallen but with my car lights on, I was able to slowly negotiate the narrow, unfamiliar roads leading to Aunt Kerani’s home where we were to stay. We followed her through the front door; it was pitch black inside. Jim was puzzled “where are the lights?” Kerani lit the wick of an oil lamp and we were soon able to get our bearings. It had been a long day so after unpacking, we went to bed.

I’m holding Theodore and am next to Aunt Evangelia and Ann; to the right is Aunt Kerani and Jim, at Aunt Kerani’s house in Aloizianika where we stayed on Kythera.

I was woken next morning by a loud and insistent beeping of a car horn. It was my cousin, Panayiotis Viaropoulos, urging me to quickly dress to go with him to Diakofti, a seaside area owned for generations by the Aronis families. To Panayiotis and to Uncle Peter Aronis, sadly left behind in an Athens hospital because of a lung infection, Diakofti was the jewel of Kythera. It was always on my father’s lips whenever he reminisced about the island. I jumped in the car as soon as possible and we headed initially towards the monastery of Ayia Moni, which prominently stood out on a far distant hill, then we veered to the right onto a rough dirt road in appalling condition with rocks and potholes every few yards. Panayiotis pulled up suddenly when he spotted a fisherman walking by the roadside with a highly prized catch – a large “orfos” (a quality fish resembling bar cod) and for a very good price he handed it to us. We continued to crawl along the road, bypassing the many obstacles and coming at last to the edge of the highland from where we could view the whole panorama of Diakofti: the long beach with a sand-bar protruding just under sea level to a small uninhabited island which served as a natural breakwater; a line of century-old dwellings hugging the shore; sparkling blue water with the transient blemish of a half-sunken ship; it was natural habitat with little development. Taking it all in, I understood the truth of what had been told me – Diakofti was magnificent and unspoilt. We slowly drove down the precipitous road and headed towards Panayiotis’ home but had to walk the last few hundred yards as the car could no longer negotiate the rough terrain. The house was spacious and comfortable with a large open veranda facing the sea and a front yard contiguous with the beach. A generator provided electricity, a luxury available nowhere else in Diakofti. I was introduced to other second cousins, George and Olga Beys, who occupied an old two-room hut on the beachfront next door to Panayiotis; it was Olga who was entrusted with the “orfos” and within three hours, had ready for us a meal fit for royalty.

Not long after our arrival and having drunk the obligatory cup of Greek coffee, Panayiotis took me for a walk along the beach at times gazing lovingly at the water gently lapping against the sand and stopping here and there to indicate which hut belonged to a particular Aronis family. We came to a “kamara”, a fully enclosed arch-like edifice of tightly packed stone and mortar, which was partly covered by the sand, and he said “this belongs to you”. Of course, he meant it belonged to my father’s family which, I was later to find, had another, larger “kamara” and land holdings away from the beach and on the eastern side of the hill-slopes which encompassed Diakofti. High above, standing dramatically like a divine sentinel, was Ayia Moni.

Panayiotis Viaropoulos and myself outside an Aronis-Beys kamara at Diakofti in 1966.

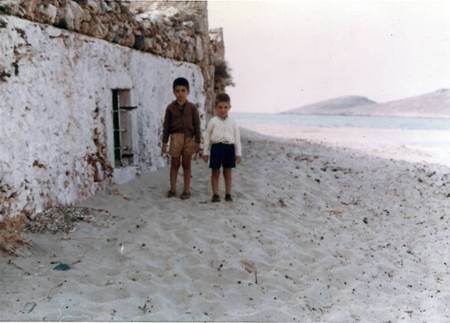

Jim and Theodore outside the Aronis-Beys kamara on the beach at Diakofti in 1966.

Early afternoon, sacrificing some of his siesta time, Panayiotis drove me back to Aloizianika where everyone was waiting impatiently for me to return so we could go to the prime destination, our home town Aroniadika. I parked the car in a small clearing only fifty yards from the church of Ayios Sotiras and we walked slowly through a maze of narrow paths between rows of houses most of which were abandoned and derelict. This once lively village had lost its inhabitants to Athens, America and especially to Australia where more than forty thousand people of Kytherian extraction were living in Sydney alone. Some had remained to look after the old people and eke out a living tending olive groves, grape vines, gardens and livestock. Minas Viaropoulos, the town mayor, said words of welcome and took us to what was left of our family homes. In so doing, we met up with Aunt Erofile and her son Basili who were holidaying in Aroniadika at the time, and together we walked to the home of my grandfather, Emmanuel Aronis (Beys). The lower level, built on both sides of a narrow public pathway, was intact, though grossly neglected; on one side were steps leading to what was once a substantial upper storey but had degenerated to a total ruin. A feeling of sadness descended on me to see the fate of so proud a home. I lingered for a time then joined the others who had moved on to the disused village square. Asking many questions, I tried to conjure up a mental picture of what it was like when my father was departing. We went on to my maternal grandfather’s house and, though long abandoned, both the upper and lower levels looked to be structurally intact. It must have been a fine building in its day. Further along, downhill from Ayios Sotiras, towered a large, two-storey structure with high walls and no roof which, we were told, was the unrealised dream of Uncle Minas on his return from Australia in 1925. He married Kalliopi, a local girl, and opened a small shop in the village centre but it yielded little profit so with his funds becoming rapidly depleted he was unable to complete the house which today remains as he left it. Taking Kalliopi, he departed for Sydney and re-entered the lucrative cafe business but it was his destiny to lose both his wife and his money. Our tour would not have been complete without a visit to the “kafeneio”, a shop serving coffee, drinks and savouries, and used as a meeting place for the villagers, especially in the evening. There we were treated as long lost children of Aroniadika and the ouzo flowed freely in celebration.

My father’s family home in Aroniadika.

The next day we drove half a mile west of Aroniadika to the small village of Pitsinades, which my father-in-law Theo Pascalis left in 1909 to come to Australia. His family home, long disused and showing the ravages of time, stood tall on an elevated location but the walls of the upper storey were yielding to the pressure of the roof and it was in danger of collapsing. We stopped by Ayios Sotiras a number of times until we succeeded in finding the priest in charge. He unlocked the large wooden doors allowing us to enter and take in the full splendour of this great church, one of the largest on the island. Construction had commenced in 1911 and was not completed until 1930 so my parents would have worshipped in the old church, no longer existent, but virtually on the same site. I felt I was walking in their footsteps. Each of us lit a candle for ourselves and for others dear to us, both living and deceased.

The second week of August saw Kythera swamped with visitors, not ordinary tourists who happened to choose the island for a holiday but, almost without exception, returning Kytherians or their progeny. It seemed like the gathering of a vast extended family with a strong seasonal homing instinct. They were to be found in all the villages and resorts but tended to congregate most often in Potamos, the largest town of the north and the commercial centre of the island. Working our way through the crowded square and the two “kafeneia”, we were surprised to run into so many people we knew from Australia. They were very much in holiday mode and a spirit of exuberance prevailed especially on Sunday mornings when everyone converged on Potamos for the weekly markets.

We promised Panayioti we would spend a few days at Diakofti – he couldn’t understand why we wanted to be anywhere else. I drove very slowly along that dreadful road, then down the hill, leaving the car in a paddock some distance from the house. Panayioti had moved his neighbours out of their hut and, with extra beds brought in, placed it at our disposal. Each day we were confronted with huge amounts of food, for the Viaropoulos family believed in eating very well, then we would rest on the veranda, or spend time wallowing on the sand and in the water. For the boys it was delightful swimming in the calm warm sea though after each dip, blobs of tar which came from the sunken ship had to be washed off using a cloth soaked with kerosene. The three-hour siesta drove me crazy – I wasn’t used to it. While everyone else slept, I walked up and down the beach several times then sat on a chair under a tree, drink in hand, looking at the sea and wishing the hours would pass more quickly. After dinner, about 10 p.m., it was time for bed so with a torch in hand, we went next door where Ann, the children and I slept in one room, Evangelia and Nina in the other. I usually sat outside for an hour or so to experience the absolute stillness, apart from the rhythmic gentle lap of water. The sky was so clear, crowded with stars. Four days we stayed and in that time, Panayioti pointed out my family fields and, as well, told me some of the history and life experiences of the Diakofti dwellers. The Aronis families had garden plots there, kept herds of goats on the nearby island, fished in the waters, basked in the cool sea breezes in summer. Remarkably, a plentiful supply of fresh clear water was available from wells less than one hundred yards from the sea. It seemed idyllic but I was made aware of a darker side. Panayioti explained that in earlier times, Turkish and Algerian pirates raided the settlement to take captives for the slave markets of North Africa; he led me to a huge cavern, its entrance obscured by vegetation, where the inhabitants hid when warned of impending danger. He went on to tell of terrible outbreaks of tuberculosis where those contracting this contagious and deadly disease would be driven from their villages to live and die in the isolation of Diakofti. Panayioti said “do you know how many people are buried under these sands?” The stories fuelled my superstitions and to me the whole place had a scarey feel about it. On the fourth night we were all in bed when suddenly Nina screamed hysterically. I ran to her and in the light of my torch saw a huge rat scurrying about the floor; it had fallen from the ceiling onto Nina and she was shaking with fear. That incident marked the end of our stay in Diakofti and in the morning we left for Alozianika.

August the fifteenth is one of the great religious days of the Orthodox calendar, commemorating the dormition of the Holy Virgin Mary. Kythera has many monasteries and churches but the most revered of all is the Monastery of the Panayia Myrtidiotissa built where an icon of the Madonna and Christ Child, credited with miraculous powers, was found at some time, as yet unknown, between the 12th and 14th centuries. We went there for the great liturgy and found ourselves in the midst of three to four thousand worshippers who were being systematically ushered into the packed church then, having lit a candle and kissed the base of the icon, were led out to the surrounding area where the service could be heard and followed. It was an emotion-charged experience enhanced by the fervour of the believers and by the warmth of interaction in this holy setting with so many relatives, friends, and acquaintances. I placed in Jim’s hand a good sum of money to give to a sad-looking man who seemed down and out – if a good deed were to be done then this was the place and time to do it. The final enactment came with the parading in the church environs of a replica icon in a procession led by a brass band with the Metropolitan, priests, parliamentarians, community leaders and the general congregation following in what was a deeply spiritual aspect of Kytherian life.

The procession of the icon of Panayia Myrtidiotissa on 15th August 1966.

The feast day continued with a huge celebration that evening in the square of Potamos. I was greatly looking forward to this, having been brought up on traditional Kytherian music with the time-honoured themes of love, sadness and nostalgia for the Kythera of old. Surely this would be one of the emotional highlights of our trip. We had a good table, secured by relatives who went early and, by 9 p.m., had eaten well and drunk much wine. It was time for the music to start and as the band emerged, I stared disbelievingly as my barber from Sydney walked onto the stage holding a saxophone, with three others following him. For the next two hours or so we were assailed by third rate western music played by a fourth rate outfit. The wine kept coming and as time went by, I became more and more agitated to the point where I bitterly complained to one of the organisers “I didn’t come half way around the world to hear this rubbish”. He calmed me down and told me to be patient. At midnight when the party reached its alcoholic zenith, the band departed and a true Kytherian group took over which, to my mind, was first class as they beautifully rendered the sentimental, haunting Kytherian melodies I was craving to hear. The combination of setting, music, atmosphere and emotion bordered on perfection.

The following week was spent touring the historic monasteries and churches of Ayios Theodoros, Ayia Elessa, Ayia Moni, Panayia Orfani, and many others. Often we bought loaves of delicious freshly-baked hot bread from a bakery at Potamos and ate chunks of it as we drove from place to place. We lunched with cousins Katina and Vasili Mavromatis at Friligianika, Manuel and Potitsa Alfieris at Ayia Pelayia, and with the family of Michael and Irine Samios (Hamouzas) whose house in Mitata overlooks a magnificent valley. It was there that Jim and Theodore took to a large container of wheat while the adults were inside the house eating, and they scattered it all over the courtyard. Ann and I were very upset but the Samios family good naturedly passed it off with mock admonishment and laughter.

A day was devoted to driving south to Hora, the capital and administrative centre of the island. The land looked greener and more arable than in the north while Hora itself was very much the classic Mediterranean island town with gleaming white houses clinging to the hillsides, a plethora of small churches and many well-kept buildings. Here lived the Venetian overlords of former days as well as the better-known and wealthier Kytherian families. The town square was well cared for as also were the small shops and offices lining the maze of narrow streets. We were anxious to walk beyond the town and up to the Venetian fortress, constructed over the period 1312-1503, which for several centuries dominated a wide expanse of sea and gave protection and sanctuary to the people of Hora. It had become a major tourist attraction drawing visitors from afar to Kythera. Holding onto the children, we wandered about the remains of the massive fortification, exploring it, taking photos and scanning the views it offered from many vantage points. A road winding downhill from Hora took us to the picturesque port of Kapsali, a popular beach resort with a long pebbly stretch of sand and a pleasant seafront walkway past an array of shops and houses. Looking upwards, Hora and the towering fortress presented an unforgettable scene of picture-postcard quality. The boys swam while the rest of us sat at outdoor tables protected from the burning sun by large umbrella-like shades, quenching our thirst with cool drinks. The evening was fabulous as a friend, Mr Simos, had organised a very congenial get-together at one of the tavernas on the waterfront where we had a sumptuous meal of seafood and Greek-style bouillabaisse.

Towards the end of our stay in Kythera, we visited a distant cousin known as Lambroandonis who owned land at Paliopolis (old city) to the south of Diakofti and separated from it by a steep hill and headland. Sitting contentedly under a large trellis covered with grapevines, he called this his personal paradise. As we were lunching, I noticed a group of men close by who were not Greek in appearance and demeanour, and I asked “who are these people?” to which Lambroandonis nonchalantly replied “oh, just English archaeologists”. It was Professor G.L. Huxley of the Queens University of Belfast and his team of archaeologists who were excavating part of the ancient Minoan port of Skandia. Huxley showed me over the digs, explaining that much of the old city was now underwater as the coastline had silted and changed over the centuries. To me it was mind-blowing to think that this beautiful field on which we stood had such momentous secrets.

Huxley strongly urged me to see the ruins of the Byzantine city of Ayios Dimitrios at Paliohora which was devastated in 1537 by the infamous pirate Barbarossa. I rounded up thirteen people for the expedition to Paliohora on what was to be our last day on Kythera. Among them were Nina, the Venardos family from Bathurst, west of Sydney, and Spiros and Eleni Kamariotis from Aroniadika who, having lived all their lives on the island, must surely know the way, I thought. Ann and the boys didn’t come as we were warned the terrain was very rugged. We took three cars to the village of Trifilianika then proceeded on foot along a barely perceptible goat path which gradually petered out. We knew we had to head east and after a lengthy and difficult trek, we finally entered the ghost town of Paliohora which had been strategically built on heights where two gorges converge; steep cliffs offered natural protection and only from one side was it accessible. Following its destruction, the city was never restored and no-one has lived there since. Local people believe it to be haunted. We didn’t know this at the time, but it was eerie that a lone candle was burning in a small church as we entered the citadel, and we couldn’t find anyone. After a couple of hours inspecting the ruins, we decided to go back, driven by the fact we had no water with us and the whole area was absolutely parched. In the fierce heat, we tried to retrace our steps but became hopelessly lost, initially following a rock-strewn, dry riverbed then, as the sun set, laboriously climbing a hill which, like all the others, was densely covered by bushes with hard spiky thorns. Spotting the distant lights of Potamos, we stumbled along in that direction and at long last came across our cars. It must have been quite a spectacle for those in the ‘kafeneio” when the thirteen of us tumbled in, agitated and extremely thirsty; the girls had worn shorts and their legs were covered in blood, a legacy of the thorns. On a later trip to Kythera, I found we had become part of the local folklore, being referred to as “the crazy Australians who nearly died going to Paliohora”.

Standing in the ruins of the Byzantine city of Ayios Dimitrios at Paliohora.

Early the next morning, a hurried farewell to Aunt Kerani, then we were on our way to Ayia Pelayia to catch the boat coming from Crete which would take us to Piraeus. I left Kythera with a deep sense of nostalgia and an irrevocable feeling that part of me would always remain with “the island”.