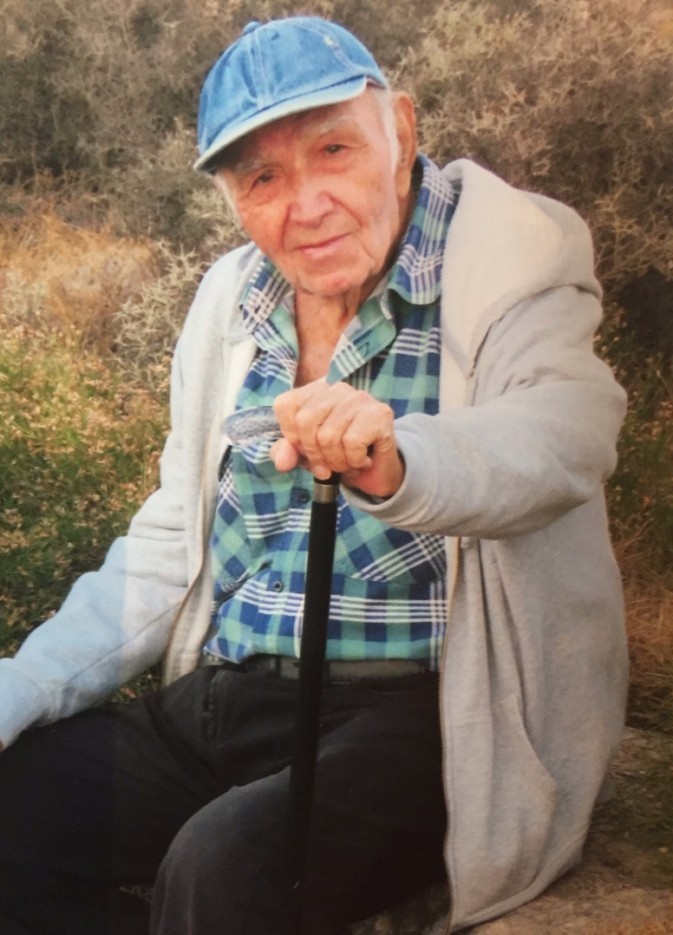

Andreas Kalokairinos

These are some memories of Andreas Kalokairinos' life on Kythera before he moved to Australia. He was kind enough to tell them to me a few years ago for my book The Kytherians. Andreas died in April of 2019 on Kythera. He will be missed!

James Prineas

MEMORIES OF ANDREAS KALOKAIRINOS

There’s one thing I’m proud of about myself: I’ve got a very good memory. With more recent things I’m not so clear, but still for my age I’m doing all right.

Although my parents and I were born in Alexandrathes, my maternal grandmother Maria Aroney was from Aroniathiaka. And from what I know about her, she was an immigrant to Smyrna because in those days, most of the Kytherian population who left the island used to go there. And also my great-grandfather, from my father’s side, went to Smyrna. Actually I still have a couple of things of my mother’s from there like copper pots and a coffee grinder with writing on it, dated 1888. They have her initials – M.A. – engraved on them. My great-grandfather left here very poor and he ended up becoming rather rich in Smyrna. He had a sort of factory for making drinks. Liquor drinks. When he came back he bought a big property here.

I’m a Kalokairinos from both sides of the family. They weren’t related but had the same surname. Grandmother Mary married Manolis Kalokairinos, whose family nickname was Foudoulis.

My father’s father, I’ve got his name actually, was Andreas Kalokairinos. My father’s mother, she was a Tzannes from Agios Ilias, and her first name was Diamanta. I remember them clearly. As a child I spent quite a bit of a time with them. They had a large property and they also used to take me to do the alonisma, the threshing of the wheat. They had oxen. I’ll never forget how hot it used to become while threshing in the summer. It had to be done in the middle of the day because the heat was needed to keep the grain dry. Very hard work. First we put the wheat in the middle and then the animals walked on it, breaking the wheat under their hooves while someone chased behind to make them go round and round and round all day. Sometimes someone sat on a donkey to keep the oxen moving. And then in the afternoon they took the animals out of the round and separated the grain from the chaff by throwing it up in the wind.

The ahiro, the chaff, was collected and kept in a storeroom as food for the animals. They put the grain in big bags and kept it in the storeroom too. Then they took it bag by bag to the mill. In those days we went to the Mylopotamos watermills but there were windmills on the island too. I went with my grandmother very early on a Sunday – it being the only day we didn’t have other work – and left the bags with the wheat. The next Sunday we would go again to pick up our flour.

I remember going to weddings with my mother. Everyone sang and mother had a good voice and she enjoyed it. She was usually quite happy. I often think about the people back then: they were poor, they worked very hard, and they didn’t have much to eat. But still they had time to tell jokes, to laugh and to sing. I was one of them myself – I never came back home in the night without singing, even though I was dirt poor and I worked hard. The only thing I had was my youth. But I see the young people these days and they never smile.

We used to go next door where two old people lived – that was the gathering place of the neighborhood. Musicians came: one played violin and the other the lute. They sat on a stage and all the others, young and old, danced.

We had to go to Karvounathes if we wanted to buy anything. In my grandfather’s time there was a little shop at the top of our village – a café and store – but by the time I came along there was nothing. No shop, no nothing. For shopping we had to go to Karvounathes or Tsikalaria, or Livathi. And we had to go to school in Karvounathes and Kondolianika. So you can imagine going barefoot, every morning – on very cold mornings in the winter – to walk all the way to Karvounathes or Kondolianika. The priest had made a mistake with my year of birth: he declared me a year older than I was so I had to start school a year younger than the others. It took about an hour to get there. Early in the morning.

There were puddles with water that froze over in winter and I enjoyed breaking these with my feet. Other kids did it too, the only difference with me was that I was a year younger.

The teachers were real cruel. Most of them. Sometimes you had one who was a little bit better. Though it was strict I think we learned more than with modern ways. If they had been a bit kinder I would have preferred it though. I remember trying to write with very cold hands and making mistakes and they came and hit me with a stick. They were cruel, very cruel.

One thing about me is that I wasn’t supposed to be a good student. But whenever there was something difficult to answer, the teachers asked me. Once an official from Athens came to inspect the school and he asked a question which nobody could answer. So I lifted up my hand and the teacher went very red because she thought I’d say something foolish. I finished up having the correct answer and even the teacher and the others thought I would get it wrong. I beat the lot.

Even with school I wasn’t very lucky because war broke out and they closed the schools so I lost a year. Later on I had to go back and have some lessons privately to try and get the certificate.

My father was in Australia. He left when I was two-and-a-half and I didn’t see him again until I was twenty-four years old. I think he was born in 1910. Minas Andreas Kalokairinos. I was the first born – in 1926 – of three children. My sister Diamanta was born in 1927. When my father left my mother was pregnant with Manolis who was born in 1929. But my father had already left.

My mother had a brother and he left at four years of age and went to Australia and managed to make money there. So they decided that my father should go to Australia and stay for four to five years to make some money and come back. So he left in 1929. He went to a little village on the New England Highway called Melville. My uncle had a shop there called ‘Blue Bell Café’, and later on my father bought it.

It was a common thing those days for the men to be away. Mother had to do everything. To tend the garden, to work the fields, do the threshing, to bring in the harvest. The children had to be taken care of as well of course. She didn’t have any help, until we children were old enough to help ourselves. Father sent money back whenever he could but it wasn’t much because he had to pay off his ticket to get there and then to buy the shop. During the Second World War he couldn’t even send any money, but fortunately by that time I was twelve and had stopped going to school in order to help my mother with all the work. I had to work for three days a week for an uncle of mine so I could use his animals for one day in my fields. I was clever enough to go and find another uncle of mine who had a cow which had a little calf. I gave him twenty okas of olive oil and I bought that little calf which, when it was a bit older, I teamed it up with our donkey to stamp the wheat and plough the fields.

Mother looked after all of us alone. Actually I had to look after them too. I remember Mother made a suit for me, from linen. She grew the flax in the field, harvested it, and out of the stalks which had to be scraped and spun and woven, she made the material for a whole suit.

Almost every day we ate the same thing. Either fava – split peas – or things from the garden. During the war we had a bit of a problem getting enough grain for the bread. We had almost enough because we had the fields and that helped us out, but I wouldn’t say we had plenty.

The idea was that father would send back enough money. That never happened actually. Or when it happened, it was too late. He came back in 1957, twenty-eight years after he left. Mother was lonely all those years without him. She was. But that didn’t happen only with my parents. It was a very common thing here on the island. The worst part was when the war broke out and we didn’t even get any letters from him any more. For the first years when the war was on we didn’t even receive a letter. We didn’t know if we was alive or not.

For a period, when I was still small, I had like a business partner. He was about the same age as me and his father had died in America, so we were both without our fathers. He had an ox and, with my donkey, we became partnered up and later on he finished up marrying my sister too. We went from being friends to partners and then we became brothers-in-law.

The only time people in the village really went swimming was after the harvest. They used to take stalks to the beach to wash them and have a day at the sea-side. We went to the beach next to Kalathi called Vlihatha, about an hour’s walk from here. There’s a lovely cave there.

One time a man from my village went down there to clean the stalks with his wife and two daughters. They spent a day there and the waves washed in a tree trunk and he thought it might be a good idea to take it home, because wood was valuable back then. The same day, two young shepherds came to have a swim and they offered to help him carry it if he came back the next day. Probably because he had two lovely daughters whom they wanted to see again. In the morning he saw me and asked if I would like to come. It was a silly question – of course I wanted to! I was about ten years old. Something like that. And it was during the war. So we went down there and they started to cut the trunk. It was very hot and hard work. For lunch we went into the cave. They had brought a frying pan and everything and they cooked there and we had a lovely lunch and lots of jokes were told. It took me a few years to understand some of the dirty jokes they told in that cave. After lunch they had to go back and start sawing the log again. The man told me to stay there and wash the plates and the frying pan, and not get into the water. He felt responsible for me and didn’t want me to drown. A few years earlier, another group had gone there and a man had drowned. So I washed the things and put them out in the sun on the beach to dry. It was lovely and cool in the cave. I lay there and started singing and fell asleep.

Later on I woke up and the plates and everything had disappeared. The waves had pulled them out. I wanted to get them but he had told me not to go in the water. But I had no choice. So I dove in and rescued all the plates. When I had everything out and was still alive, I thought I might swim some more. If I swam behind the rocks they wouldn’t be able to see me. I swam towards Kalathi. It was beautiful looking down to the bottom – the water was very clear. All of a sudden I saw a lot of bottles down there – about fifty of them. Bottles were hard to get in those days. I dived down and brought one up. It was like the ones they have in Australia: big beer bottles with the stopper on the top. In the meantime another boy from Keramoto appeared. He was a bit older than me and was fishing for morays there. I called to him to have a look. Neither of us could tell what was in them. We recovered them from the water and divided them up fifty-fifty. But they were heavy!

There’s a suicide path – steep and rocky – on the cliff behind the beaches. Loaded with the bottles, we went all the way along that path to the other beach. I put mine in the cave. But what could I say to the fellows that I came with? They had told me not to go into the water. So I took them one of the bottles and said: “What could this be?” Like I didn’t know nothing. They opened the bottle, smelled it, tasted it, and there was no taste, no color, nothing. It was almost evening and we had to go. We loaded all the full bottles on the donkeys and took them back to the village with us. Later on we found out that much of the German army in Crete had typhus. The bottles were full of special water for the them and the ship which was bringing them help had sunk and the bottles somehow ended up in Kalathi.

In 1943, a day before Easter, British airplanes sank a German boat in Avlemonas. I heard the planes and I ran there. My mother was screaming for me to come back, but I ended up in Avlemonas. It looked deserted. Half of the population had hidden themselves at Palaiopoli. I walked towards Cavalini’s café – the house with the sundial. Suddenly I saw a big group of Germans there with a machine gun on a bench. They might have been suspicious of me if I had run away, so I acted like nothing special was happening and walked right past them. I knew that the owner of the café lived on the second floor and that he was paralyzed. That was Mr. George Cavalini. His wife and his sister and son Spyros were hiding. So I pretended to go upstairs and see the old paralyzed man. I entered the café. They had put all the tables together and the German doctors were operating there. I’ll never forget that picture. Blood. Screaming. So I went upstairs and saw Mr. Cavalini. We exchanged a few words but I don’t remember what we said and I soon left. Outside, where there was a bench and a lot of soldiers. One German was covered in blood with bandages wrapped around his head. He signalled me to come over and opened his wallet. He took out a picture and started telling me something in German, showing me a picture of a boy and was trying to tell me that he had a son like me. That made it easier for me. I felt better. I watched what was going on: one of the Germans had a bullet hole right through him and he stood up and pulled up his shirt. Someone was putting bandages on him and another told jokes to keep him happy.

I remember when the war began. It was 1940. The 28th of October. I was returning from the mountain where I took the goats to graze – I used to stay with them up the mountain all day. I was studying English on the mountain by myself. I had a method with no teacher. I make jokes now about it: I call that spot there up on the mountain, “The College,” because people ask where I went to college. A friend of mine even put it on a map and called the mountain “The College”.

Anyway, when I returned home it was evening. My mother told me that the Italians had attacked us in Albania. I remembered the teacher told us that we had problems at the boarders there in Albania because the Italians threatened us. The prime minister of Greece, Metaxas, made a line there, a war line, and said: “We hope”. I remembered that. And when I heard that the Italians had crossed the line, I cried.

They created a battalion here on Kythera. They had one in Agia Moni and another one in Hora and in other parts of the island as well. They were stationed here for a number of months. When they finally got a signal they had to leave and only a small number of soldiers stayed here.

Before they left, all gathered in the square of Karvounathes. I went barefoot to the village square. It was night. All the soldiers had gathered and someone was hungry and was complaining to the officer who opened his jacket and said: “Eat my flesh. I haven’t got anything else to give you.”

They were dispatched to different regiments, but most of them went to the front line in Albania. One of them I knew – he had taught me some music – was from Agios Ilias. He lost one of his legs. The Greeks threw almost all of the Italians back into the sea. We beat them, the Italians. But then the Germans butted in and they pushed us back.

The Germans came to Kythera first with motorbikes and later they were followed by the Italian carabinieri and army. They came through Agia Pelagia and went to Hora. They ended up at Agia Elesa and in Trachila where they built their base. We had to go and work there. They sent a message to the mayor of each village, and the mayor had to send a number of workers each day. By then I was about four and I had to go too. I did more damage than good for them: I was supposed to roll a barrel somewhere and I pushed it down onto a rock and broke it. Then I had to repair it.

The silliest thing I did was when I decided to pinch a grenade. At Trachila there is a big natural cave and that’s where they stored all the ammunition. I thought if I could manage to find the box with the grenades I could take some and use them for fishing. Instead of dynamite I could use grenades. I told a boy from Aroniathika to lie down and give me a signal if anyone came. I walked into the cave and started to look for the grenades but I couldn’t read German. Up on the hill was a German with a machine gun on a tripod. He saw me and yelled. I couldn’t hear him in the cave so he started shooting into the air. He signalled to me to come out with my hands up. I walked outside and just then the bell rang announcing the end of work. I ran to the others who had gathered and mixed myself amongst them. I took off my coat and put it under my arm just to look different so the soldier wouldn’t recognise me. I got away with it, but that was a very silly thing to do. If they had caught me with the grenades they probably would have shot me on the spot.

As far as I remember, only one person was ever killed by the Germans. In Agia Pelagia. He was unlucky and probably a bit silly. The fellow was from the Peloponnese and had sailed to Agia Pelagia. His nephew had hidden a gun in the boat without the uncle’s knowledge. When the Germans searched the boat and found it they arrested the uncle. After a few days they took him somewhere and told him to dig his grave and after that they shot him. He was the only man who was killed by the Germans on Kythera.

At the end of the occupation, as soon as the Germans left, five or six parachutists landed at night in Drymonas. One of them was an American, the others were English. As soon as they landed the villagers started to celebrate: the bells rang and there were bonfires lit. It was three or four o’clock in the morning. I started to run to Drymonas: a crowd had gathered there. A priest started to hold a service: it was around Easter time. Instead of saying: Christos Anesti – Christ has risen – he said: Hellas Anesti– Greece has risen.

A day or so later the parachutists left but after a week the British came to Kapsali. I had been learning English up on the mountain so it was a great opportunity to test myself. I had a conversation with a British sailor and we became friends. He invited me to visit him on the boat at 5 o’clock the next day. I was so proud. I was supposed to go to the boat in a dinghy and while I was getting in, a bloody communist started to shout at me. He pulled me back. So I jumped out and I started to hit him. And I was very strong from all the heavy work I did in the fields. He had a pistol but I was kicking him. Another communist arrived and they wanted to take me to their captain. I was thinking of how to escape. We walked around the houses and, when we reached the corner where the road went to Hora, I dropped behind and then ran away. But instead of going towards Hora I went around to the other beach at Kapsali – Piso Gialo – because I had a friend there with a house to hide myself in. But outside the house was another communist. Before I could explain why I wanted to get into the house, the others arrived and caught me. The one I had beaten up wanted a gun – the pistol he had must have been without ammunition – from the man outside the house. But he wouldn’t give it to him.

While they were fighting I changed my plans. I thought that, even if I got away, they would go to my house and burn it down like they had done with others. So I said: “You don’t need that gun. I’ll come with you”. So we went and I was bloody lucky, because a week earlier, in the next village, there was a doctor and he was chased by the communists and they burned his house down. They came and searched our house because they suspected I was hiding him. I was sitting outside with their commanding officer while the others searched my house, looking for the doctor. We struck up a conversation and we got on really well. His name was Nikos Macheras. So anyway these communists who had caught me took me to their commanding officer, who was Macheras – the officer who had been with me outside my house. When he saw that I was in trouble he told the others that they could leave me with him and that he would “deal with me”. He waited for them to leave and then he let me go.

All in all, we suffered much more with the Greeks in the civil war than with the Germans and the Italians during the occupation. The communists here were a minority but a large number came from outside Kythera. They had guns and burned three or four houses. They took four or five people and threw them into the ocean and drowned them. One was from Australia. His name was Jim Kokkineas from Zaglanikianika and he came here with his wife and three daughters and he was an outspoken anti-communist.

I first kissed a girl before I went to the navy; I was fif or six years old. The funny thing was that I had an uncle who was trying to make me a good Christian. He told me that I had to be good. But kisses were sweeter than paradise! Anyway I kissed a girl from the village secretly. I can’t mention her name – she’s still alive.

After the war, from the 1st of August to the 15th, the religious people went to Myrtithia and stayed there for fif days. I wasn’t that religious but, because many young people went there, I told my mother that I would like to go too. Many people from America and Australia used to come to stay there. Each night we all danced in the square outside the monastery. The young people would dance and I played the music. We had a wonderful time. And we met lots of girls from Australia and from America. I met a girl there who was from Australia. Probably that helped me to decide to go there. I even ended up going there on same ship with her. It was just a coincidence though.

My mother was bitter: she used to say that Australia took her husband first and now it was taking her children. My brother didn’t have to do military service – he had a problem with his eye – so he went to Australia before me. Mother had lost one child already to Australia and then she was going to lose me too. That’s why she was saying that Australia took her husband all her children.

Dad asked her to come to Australia but she didn’t want to go. She just wanted to be here, on Kythera, with her sister.