More to Aphrodite than meets the eye. Exhibit explores sexual power

By Sebastian Smee

Boston Globe October 30, 2011

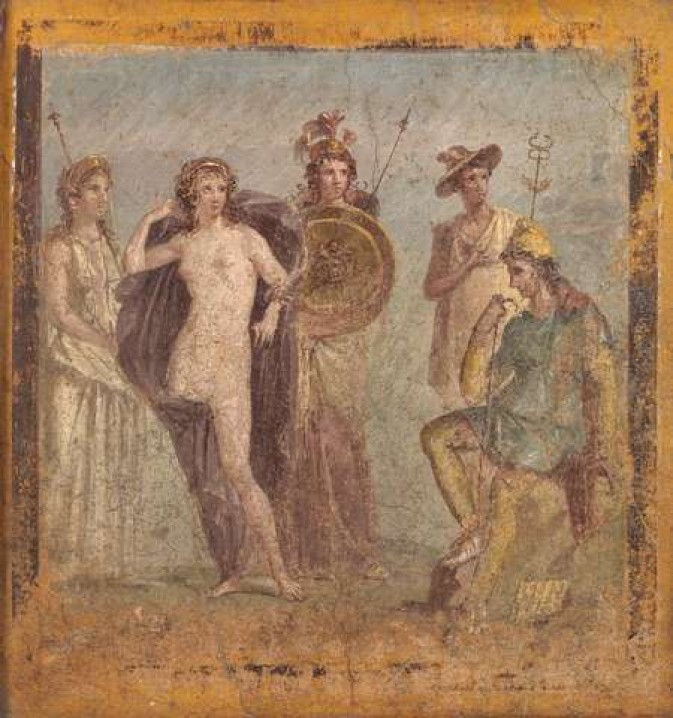

The Judgment of Paris – Itallic, Etruscan, Hellenistic Period, late 3rd – 2nd century B.C. small

Exhibition will move to the Getty Villa, California, from March 28th to July 9th, 2012.

Don't miss it!

MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS

Greek myths give the sadly tarnished idea of received wisdom a much-needed boost. They elucidate truths we, today, can barely bring ourselves to acknowledge. Addressing not just pride and mortality but sex, violence, flux, and promiscuity, they provide a space for glimpsed but rarely addressed truths to gain traction in our lives.

“Aphrodite and the Gods of Love’’ at the Museum of Fine Arts is a very beautiful, very smart, very orderly show that is also a kind of hymn to the Greeks’ apprehension of the power of promiscuity - of mixing things up.

The exhibition is billed as the first museum show devoted to Aphrodite, the goddess of love, who was known to the Romans as Venus. Its pairing with the MFA’s concurrent “Degas and the Nude’’ is a rare instance of programming genius: Both shows stir up unsettling thoughts not just about female nudity and beauty, but about seduction, vulnerability, sexual power, and the sacred.

The objects in “Aphrodite’’ are drawn mostly from the Greek and Roman holdings of the MFA, which are among the best in the country. But it also includes 13 loans, nine from Italy. The loans are the fruit of the MFA’s decision, in 2006, to return to Italy a number of disputed objects in its collection, and to set up procedures to ensure it doesn’t acquire stolen art in the future.

That decision, and the Italian government’s promise of reciprocity, paid off for the MFA in 2009, helping to secure important loans for the exhibit “Renaissance Rivals: Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese.’’ Now, for the first time, it has led to significant loans of ancient art - including a large Roman marble statue of Aphrodite from the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Naples and - a real showstopper - a Roman statue of a sleeping Hermaphrodite, from the Museo Nazionale Romano. This sculpture has only once before traveled outside of Italy.

The show was organized by Christine Kondoleon, the MFA’s senior curator of Greek and Roman Art, and Phoebe Segal, an assistant curator in the same department. Planning for it prompted a huge conservation effort - a welcome development at a time when MFA director Malcolm Rogers, preoccupied by building new wings, has left the museum’s Greek and Roman galleries looking hopelessly outdated.

This show, by contrast, looks great. The layout must have presented huge challenges to the curators and to exhibition designer Virginia Durruty. Most of these objects - from vases and mirrors to marble sculptures - need to be seen in the round. Many, including cameos, coins, earrings, and, in shallow relief, an astonishing Roman gem showing a team of cupids making perfume, are tiny. And some - reflecting the interests of Edward Perry Warren (1860-1928), the Boston Brahmin responsible for half the works in the exhibition - are very sexually explicit.

The overall result, centered on an oval-shaped core displaying large-scale marble sculptures of Aphrodite in all her glory - is lucid, coherent, and appropriately discreet without ever being apologetic.

An early section of the show introduces us to some of Aphrodite’s forebears, as represented in Neolithic, Near-Eastern, and Egyptian art. All these figures represented not just fertility, but a feminine power that was explicitly bellicose.

Aphrodite represents a more refined version of these bloodthirsty fertility goddesses, but she is still linked with war and destruction. The Greeks, that is to say, did not indulge the modern tendency to sentimentalize love. While they certainly celebrated love’s potential for good, they also saw violence as an inevitable outcome of Aphrodite’s first responsibility: to arouse desire.

A small but startling object near the show’s entrance illustrates the story of Aphrodite’s origins. It’s an oil bottle, or lekythos. Grafted on to one side is a sculptural relief of the nude goddess emerging from a pink shell, assisted by flying cupids.

One swoons and thinks of Botticelli. But the pink shell reminds us also of Aphrodite’s sensationally bloody birth, as recounted by Hesiod. The story goes like this:

To avenge his mother Gaia, the Titan god Kronus used a curving sword, or sickle, to castrate his father, Uranus. Kronus then tossed the severed genitals into the sea. Aphrodite sprung forth from the foam churned up by the water (“aphros’’ is Ancient Greek for foam). Blown by the wind, she emerged near Kythera, and then came on land at Cyprus.

Cyprus, which was later colonized by the Greeks, seems to have been the crucial link between the Near Eastern fertility goddesses and the Aegean world in which Aphrodite, always regarded as somehow a foreign god, came to play her leading role.

Within art history, Aphrodite’s importance can hardly be overstated. Until her appearance as a nude, it was the male nude that predominated in Greek art. Women, when shown, were always to some degree concealed. The very first female nudes in the Western tradition were representations of Aphrodite, and almost every subsequent female nude in Greco-Roman art depicted this goddess.

The first known example, now lost but known to us in copies, was Praxiteles’s Aphrodite of Knidos, a monumental sculpture of the nude goddess bathing, an urn for carrying water at her side. What a moment in human history! A whole tradition begun, a set of taboos cast off, a set of loaded assumptions and rival claims unleashed!

The water, in this first great representation, was important: It connected the goddess to her birth, from the sea, and alluded to her status as a goddess of water.

Subsequent versions of Aphrodite have her holding an apple; standing with hands revealingly open or subtly indicating her genitals; wearing a crown of victory; wringing out her hair; associating with amorous doves; untying sandals; erotically veiled by “wet drapery;’’ or leaning confidently on statues of herself. They tease out the goddess’s many other roles and characteristics: not just seductress, but mother and nurturer, patroness of brides, and protector of seafarers and warriors.

Several incarnations here stand out. The first is the famous “Bartlett head,’’ named for Francis Bartlett, who provided the funds for its acquisition by the MFA in 1900. Celebrated in rapturous prose by Henry James within a few years of its first appearance in Boston, it was carved from luminous marble shortly after Praxiteles’s Knidos Aphrodite, and remains to this day one of the most admired examples of classical Greek sculpture.

The goddess’s shadowed eyes, set deep in her softly modeled face, seem to carve out a sense of interiority, much as Degas’s late bathers bend over an inviolate space defined by the contortions of their self-tending bodies.

Another highlight is a drinking cup from about 490 BC, signed by the painter Makron. It shows two key events marking both the beginning and the end of the Trojan War. That legendary conflict was triggered, of course, by Aphrodite promising the world’s most beautiful woman, Helen, to the mortal Paris if he should present her, rather than Hera or Athena, with the golden apple.

On one side of Makron’s cup, we see Paris grabbing Helen by the wrist - a loaded gesture symbolizing for the ancients both marriage and rape. Helen’s hand is limp, her head bowed in trepidation; but Aphrodite arranges her veil and encourages her to go with Paris, as she would a nervous young bride.

On the other side, the war at an end, we see Helen’s husband, Menelaus, drawing his sword, ready finally to punish his unfaithful wife. But here again, hovering behind Helen is Aphrodite, who this time adjusts Helen’s gaze so that her beauty mesmerizes Menelaus.

If Helen’s face could launch a thousand ships, it could also disarm a man, making violence seem preposterous, and even sacrilegious. It’s this second effect of beauty that has inspired beauty pageants in war-torn Sarajevo and lyric poetry from the trenches. But we ignore beauty’s potential for destruction at our peril.

Near the back of the show a separate section addresses Aphrodite’s many offspring. Among the most famous of these are Hermaphrodite - the bi-gendered offspring of Hermes and Aphrodite - and Priapus, her son with the party-boy Dionysus.

Here, the sleeping Hermaphrodite - leg erotically stretched out so that the toes pull taut a bed sheet - opens onto a theatrically darkened display of erotic sculptures, including a sculpture of a bearded Priapus, his erect and overburdened phallus supporting a cornucopia of fruit.

But of Aphrodite’s offspring, by far the most famous was Eros (known to the Romans as Cupid). His mischievous, destabilizing but profoundly procreative role - extending beyond sex and into learning, philosophy, art, and war - is central to classical culture, and thus to the whole Western tradition.

In an array of sculptural fragments and painted bowls, we see him here inspiring not just explicit scenes of athletically heterosexual sex, but homosexual seductions, as well as spanking, pedophilia, and even bestiality.

Over the centuries, our conception of classical art has tended toward the hygienic. We - and scores of artists past - have associated it with near-static ideals of order, decorum, beauty, and harmonious proportion.

But these ideals represent just one half of the classical tradition. The other half is inseparable from desire, with all its destructive and generative force, and from the Greek notion of “mixis’’ - the mingling of bodies in love or in war, the ongoing exchange been gods and mortals, and so on. Aphrodite, the most seductive of goddesses, is crucial to this half of the tradition.