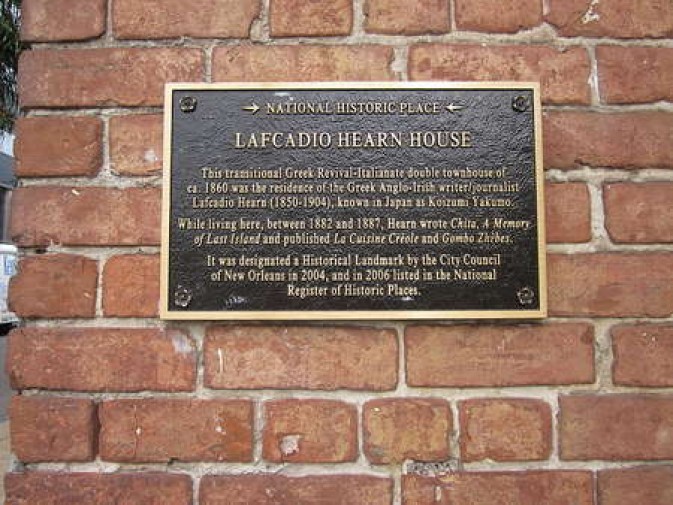

Plaque mounted on the front of Lafcadio Hearn’s former home at 1565-67 Cleveland Ave.

In 2004 the New Orleans City Council voted 7-0 to designate the home a local landmark. Hearn was a Greek-born author who moved to New Orleans in 1877. His writings about the city’s culture and traditions helped make New Orleans a place of interest worldwide.

Happy Ending for Hearn Home

SubHead A century after his death, author Lafcadio Hearn, who many say put New Orleans on the map, is recognized for his contributions

Byline By Bruce Eggler

Staff writer

Date Sunday, September 19, 2004

When the Rex organization decided to make "Lafcadio Hearn’s Fantastics" the theme of its 1989 parade, it realized that only a small percentage of residents and tourists would have any idea who Hearn was, so the krewe broke precedent and publicized the theme early.

Even so, most parade-goers that Mardi Gras morning had little notion of what the 26 floats, with titles such as "A Dream of Kites" and "The Night of All Saints, " represented, or what connection they had to New Orleans.

Fifteen years later, as the literary world this month marks the 100th anniversary of Hearn’s death, it is still unlikely that many Louisianians know much about the author, perhaps beyond the facts that he lived in New Orleans for several years and later moved to Japan.

But the small circle of local Hearn devotees had reason to celebrate as they gathered Saturday at the Old U.S. Mint for a daylong symposium on the writer, and looked forward to a gala banquet at Antoine’s Restaurant on Friday -- postponed from this past week because of Hurricane Ivan.

The reason for their jubilation: After years of controversy, the New Orleans City Council this month voted 7-0 to designate Hearn’s former home at 1565-67 Cleveland Ave. as a local landmark.

Previous owners of the building had fought the designation, even getting a court injunction to prevent the city from making the building a landmark, which gives the city’s Historic District Landmarks Commission authority to review and block proposals for changes to the exterior.

But new owner Richard Scribner, a professor at the nearby LSU School of Public Health and a Hearn enthusiast who bought the building from former state legislator and Saints star Pat Swilling in March for $450,000, was happy to see it get the landmark designation.

Besides its connection to Hearn, the Landmarks Commission said, the two-story, Greek Revival double townhouse at Cleveland and South Robertson Street has architectural significance in its own right.

Apparently built for Henry Beebe in 1861-62, it is one of the handful of historic buildings left in the medical district. Most of its neighbors were long since demolished to make way for hospitals, hotels, highway ramps or, in all too many cases, parking lots.

The "exceptionally fine" second-floor cast-iron balcony was added in 1895, after Hearn had vacated the second-floor rooms he rented for several years, the commission’s staff report on the building says.

A writer is born

Born in 1850 on the Greek island of Leucadia, from which his first name -- originally Lefcadio -- was derived, Hearn was the child of an Irish surgeon in the British army and a Greek woman. Rosa Kassimatis from Kythera. His parents separated a few years after his birth.

Raised by an aunt in Ireland, Hearn immigrated to the United States at 19 and settled in Cincinnati, where he became a newspaper proofreader and began writing articles. After a brief marriage to a half-Irish ex-slave, he moved to New Orleans in 1877.

In New Orleans, he worked as a writer and editor for local newspapers, also submitting articles to national magazines, writing several books and making a reputation as a skilled translator of French literature into English.

He became a keen observer of the city’s varied peoples and cultures, becoming, along with George Washington Cable, one of the foremost writers introducing the rest of the country to the Creole city’s colorful and unusual folkways.

Social historian Frederick Starr claims that Hearn virtually created New Orleans’ popular image in the nation’s mind.

"More than anybody else, " Starr wrote in 2001, "it was Hearn who devised the composite image that we know today as the Crescent City, and it was he who first won for that image a national and international renown. Hearn’s New Orleans is rich with diverse peoples and cultures, which he celebrated in hundreds of short essays and sketches, by writing the city’s first cookbook, and by publishing a pioneering collection of Creole proverbs. When other writers and artists later flocked to New Orleans, they sought out those aspects of the city that Hearn had immortalized, thus reinforcing the identity we know today."

For example, Hearn wrote one of the few eyewitness 19th century descriptions of a voodoo gathering in New Orleans, as well as some of the first accounts of the city’s music.

University of New Orleans folklorist Nick Spitzer, like Starr a participant in Saturday’s symposium, agrees with Starr in emphasizing Hearn’s importance in determining how New Orleans came to be viewed by the world, and even by New Orleanians. "I believe that in Lafcadio Hearn -- his life and works -- we have an intellectual and social figure whose legacy is more significant in working with enduring New Orleans vernacular culture than that of Faulkner or Tennessee Williams, " Spitzer has written.

A global voice

After 10 years in New Orleans, however, the restless Hearn moved on, first to Martinique in the West Indies for two years, then to Japan, a country that captured his interest after he reported on the Japanese exhibition at the Cotton Centennial Exposition, a world’s fair held in New Orleans in 1884-85.

Hearn married a Japanese woman, took the name Koizumi Yakumo, taught English at schools in the town of Matsue and later at Japanese universities, and performed for Japan the same task he had for New Orleans: writing articles and books that introduced Japanese culture to the rest of the world. He died in September 1904.

Hearn is far better remembered in Japan than in New Orleans or the other cities and countries he called home. His home in Matsue is a museum, and Japanese children continue to read his books in school.

New Orleanians such as Delia LaBarre, founder of the Lafcadio Hearn/Koizumi Yakumo International Center and editor of a new edition of Hearn’s novella "Chita, A Memory of Last Island, " hope to ease his local neglect by presenting an annual Hearn symposium.

And thanks to the City Council vote, Hearn enthusiasts now can be confident that a building with strong Hearn connections still will be standing years from now, and looking much the way it did when he wrote some of his most acclaimed works there.

. . . . . . .

Bruce Eggler can be reached by email Here

STAFF FILE PHOTO

The New Orleans City Council this month voted 7-0 to designate writer Lafcadio Hearn’s former home at 1565-67 Cleveland Ave. as a local landmark. Hearn was a Greek-born author who moved to New Orleans in 1877. His writings about the city’s culture and traditions helped make New Orleans a place of interest worldwide. [1094059]

Lafcadio Hearn

STAFF FILE PHOTO

The theme for the Rex parade in 1989 was ‘Lafcadio Hearn’s Fantastics.’ The float shown was designed by Henri Schindler and illustrated by Danny Frolich. [63739]

STAFF FILE PHOTO

When the Rex organization decided to incorporate writer Lafcadio Hearn in the theme of its 1989 parade, it decided to announce the theme early because so few locals knew of him. [63740]