Archie Kalokerinos 1927-2012. Doctor prevented infant mortality

Sydney Morning Herald.

March 17, 2012

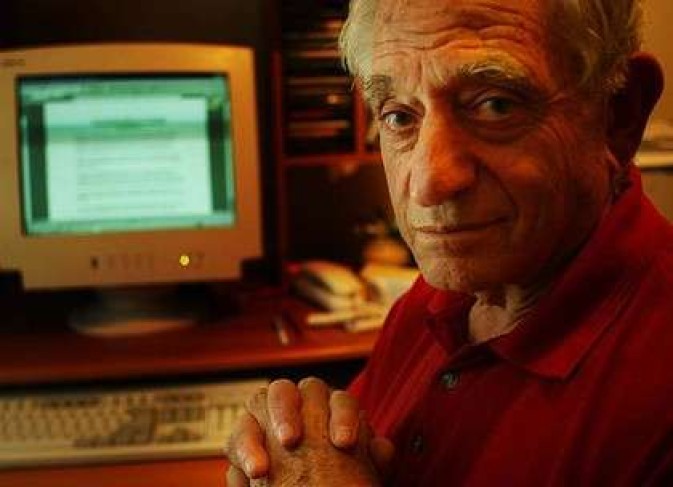

Archie Kalokerinos … created a treatment for zinc deficiency. Photo: Peter Stoop

Archie Kalokerinos, son of a Greek cafe owner, with plenty of brains and a medical degree, bounced around the world getting experience - not settling to surgery, trying general practice - until a problem came to his attention which was to preoccupy him for the rest of his life.

That was the plight of the Aboriginal people, in particular the impossibly high infant mortality rate he encountered in regional NSW. In one Aboriginal community every second Aboriginal infant was dying. Kalokerinos adopted a radical ''counter intuitive'' therapy - boosting the immune system - and brought the infant mortality rate there down to zero. He embraced preventative medicine, particularly in the beneficial use of vitamin C. Some of Kalokerinos's theories were controversial, but he had some powerful support. The dual Nobel-prize winner Linus Pauling, in the foreword to Kalokerinos's book Every Second Child, endorsed his views. In 1975, film director Phillip Noyce produced a documentary on him and Aboriginal healthcare entitled, God Only knows Why, But it Works. It was claimed that a ''Schindler's List'' could be drawn up, of children he had saved and their offspring.

Kalokerinos, who worked with the Aboriginal Medical Service at Redfern from 1976 to 1982, did not forget his origins. He once said: ''My Greek background acted, always, as the guiding light through the darkness and unknown." In 2000 the Greek newspaper Neos Kosmos named him ''Greek Australian of the Century''.

Archivides Kalokerinos was born on September 28, 1927, third son of Nicholas Kalokerinos, who had migrated to Australia from the Greek island of Kythera in 1913 and married a Greek girl, Mary (nee Megaloconomos). The couple had moved to Glen Innes, where Archie went to a local public school. In 1939 the family decided to move to Sydney to give their children better educational opportunities. Nicholas opened a shop in Old South Head Road, Rose Bay. The family lived upstairs and Archie went to a technical high school.

Archie followed his older brothers, James and Emmanuel, into medicine and graduated from the University of Sydney in 1951. He undertook 18 months as a resident at Lismore Base Hospital, then went to Britain hoping to progress to specialist surgery. He married a nurse, Audrey, there but decided not to pursue surgery, and in 1957 returned to Australia.

Kalokerinos's marriage ended in divorce. He became a hospital superintendent at Collarenebri and in 1965, frustrated in his efforts to curb the Aboriginal infant mortality rate, he joined his friend Bill Petrohelos and went opal mining at Coober Pedy, practising medicine on the side, including running a clinic at Lightning Ridge. But life was not entirely tranquil. He later wrote: ''I … found myself involved in a terrible brawl that left me with six fractured ribs and a ruptured kidney. While recovering I sought solace in the desert and that is how I met an elderly Aboriginal woman who told me that before white men came the Aboriginal children did not die as they did now.'' From that moment, he decided to return to Collarenebri to resume full-time medical practice.

He was surprised to discover that some of the children had symptoms of scurvy. After trying to treat them with antibiotics and vitamin C, he found that the effects of vitamin C therapy were dramatic. He reported on this, encountering scepticism from some within his profession. He believed there was a link between vitamin C deficiency and sudden infant death syndrome. He also found that some children had a disease that affected their taste buds so that food tasted foul, and they were being tube-fed. He realised they were suffering a zinc deficiency and came up with a treatment that is now routine.

Kalokerinos started with the Aboriginal Medical Service in 1976. In December, 1977, he married another nurse, Catherine Hunter. In 1978 he was subject of a This Is Your Life television program. He was also awarded the Australian Medal of Merit for outstanding scientific work.

In 1982, Kalokerinos decided to return to private practice and started in Bingara, in the New England tablelands. In 2002 he retired from full-time medical practice and moved to Cooranbong, on the NSW central coast. Holding several medical fellowships, including Fellowship of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health, he completed locums, pursued private research and wrote a an autobiography, Medical Pioneer of the Twentieth Century.

Archie Kalokerinos is survived by Catherine, a son and two daughters, five grandchildren and a great-grandchild.

Malcolm Brown