Lafcadio Hearn - "Almost as Japanese as Haiku"

Atlantic Monthly

December 31, 2003

In The Last Samurai, a big-budget spectacle now playing at a multiplex near you, Tom Cruise plays a disillusioned Civil War veteran hired by Japan's new emperor in 1875 to train the country's first conscript army. The culture clash that follows isn't just the inevitable friction between East and West, but a showdown between New and Old Japan: the emperor's grand plan is to consolidate his power by commanding a modern army that will supplant the samurai caste of warriors that had served the shogunate for centuries.

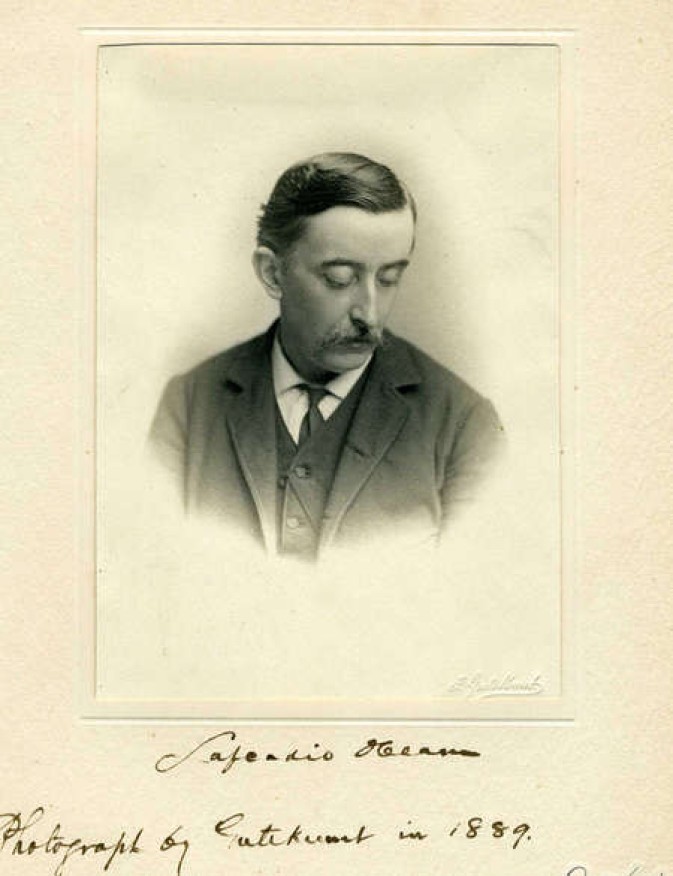

Lafcadio Hearn

It's a wholly fictional storyline, but the movie's historical backdrop offers more than its share of authentic drama. The era of the Meiji Restoration (1867-1912) saw the sweeping transformation of Japan from an insular feudal society closed off from the West to a modern industrial nation, events set in motion when the U.S. naval fleet of Commodore Perry steamed into the port of Yokohama in 1854 to open Japan to international trade. Back on the other side of the world, meanwhile, the exchange of goods was opening Western eyes to the unsuspected exquisiteness of traditional Japanese culture. A craze for all things Japanese ensued: collectors couldn't get enough of Japanese pottery; painters couldn't get enough of the woodblock prints originally used as wrapping paper in the crates the pottery was shipped in; audiences at the Savoy couldn't get enough of Gilbert & Sullivan's 1885 Japan-inspired extravaganza, The Mikado. So feverish was the vogue that Oscar Wilde (a fellow known to dote on an Oriental bauble or two) was led to quip, "The whole of Japan is a pure invention.... There is no such country, there are no such people."

Diligent readers of The Atlantic during the 1890s had it on good authority that the Japanese mystique was no myth. For the better part of the decade the magazine ran a succession of lyrical dispatches written by a strange bird of an itinerant journalist who had fetched up in Japan at the age of forty and would never return. Today we can classify him as a writer of a familiar cosmopolitan stripe—the confirmed Japanophile, the devoted cultural interpreter bent on justifying the ways of the Eastern mind to his Western kinsmen. But to typecast him sells him short. Lafcadio Hearn was nothing if not the original model.

Hearn's life may not have been the stuff that epic blockbusters are made of, but there was nothing remotely conventional about it. Professional misfit and muckraking novelist, antiquarian and iconoclast, a bohemian aesthete with a scholarly relish for ethnography and the occult, a "wandering ghost," in the titular phrase of his biographer Jonathan Cott—like any number of industrious Victorian authors, Hearn was a man of parts, only most of the parts were puzzle pieces that didn't quite fit. Born in 1850 in Ionia to a Greek mother and a father who was a surgeon in the British Army, he was raised by relatives in Dublin until the age of nineteen. Branded as a ne'er-do-well (he lost the sight of one eye in a schoolyard scrap), young Patrick Lafcadio Hearn was packed off to the United States and in time made a name for himself as a crime reporter covering lurid murder cases in Cincinnati, Ohio. In his byline he now went by "Lafcadio," the peculiar cognomen his parents had devised as an homage to his birthplace, the Ionian island of Leucadia.

In 1877 he was fired in the wake of his scandalous marriage to a teenaged ex-slave that flouted the local miscegenation laws. He then drifted down to New Orleans, where he wrote extensively on Creole life in the Vieux Carre and made botched attempts to start up a satirical magazine and a restaurant called The Hard Times. In the late 1880s he island-hopped through the Caribbean, and wrote a handful of travel sketches for The Atlantic that made up part of his 1890 book, Two Years in the French Indies.

It was largely owing to Hearn's knack for what the painter James McNeill Whistler liked to call "the gentle art of making enemies" that he came into steadier work contributing to The Atlantic from overseas. Before sailing to Japan in 1890 to take a modest provincial teaching post, he had wangled a commission from Harper's Weekly to file a series of articles on the Japanese scene. In the event, gripped by what Atlantic historian Ellery Sedgwick describes as "some discontent magnified by paranoia," he assailed Harper's editor Henry Mills Alden with a torrent of abusive letters, renouncing all contractual obligations. The performance was not exactly out of character: Hearn had a history of locking horns and falling out with his editors, practically making a career of wearing out his welcome.

How then did Hearn and The Atlantic manage to get along so warmly? Serendipity seems to have been the secret ingredient. In Horace Elisha Scudder, the magazine's newly appointed editor, Hearn found a man who already had an avid interest in the traditional cultures of the Far East—and one who evidently gave him leave to hold forth on just about anything under the rising sun. Scudder, for his part, might have felt like he had a tiger by the tail. Merely a productive writer in the States, Hearn wrote prodigiously after settling in Japan. Over the next fourteen years until his death, he churned out volume after jampacked volume of "reveries and studies"—the beguiling subtitle of his 1895 collection Out of the East, and perhaps as fitting a rubric for the yin and yang of his literary sensibility as there could be—and never was there a sign that he was running out of material. Every bit as impressive as his sheer output (his Atlantic pieces make up just a fraction of his writings on Japan) was his omnivorous range: even in a time when journalists were often presumed to be generalists, Hearn went well above the call of duty, hardly ever seeming to come across a subject he felt was beyond him or beneath him. He wrote elaborate disquisitions on Japanese aesthetics and Japanese etiquette. He wrote elegant appreciations of the Japanese martial art of jujitsu and the Japanese affection for pet singing crickets. He wrote with equal gusto and nuance on the proper schooling of Zen monks and the proper training of Kyoto geishas. When he wasn't setting down his impressions of Japanese village life and social custom with a novelist's eye for emblematic detail, he was collecting Japanese ghost stories and unearthing samurai legends with the delectation of a born connoisseur.

This was clearly no case of ordinary reportorial zeal. Hearn wasn't simply making a respectable living off his inside scoops on the unknown Japan—he was going native. It was his boldest effort yet to shed his outcast's skin, and this time the metamorphosis was complete. The "wandering ghost" finally put down roots, marrying the daughter of a downtrodden samurai (thus adding "bigamist" to his checkered resume, some have suggested, since there's no record of a divorce from his first wife) and raising a family in the hamlet where he taught secondary school. He adopted the Japanese name of Koizumi Yakumo and became a naturalized citizen. By the time he died of heart failure, in 1904, no longer was Hearn regarded as just another gaijin—the epithet for foreigner—but was eulogized by the Japanese as their "gaijin laureate," the one European author who could see into the Japanese soul. Much of Hearn's work is long out of print, and Anglophone scholars now tend to treat him as a minor period curiosity rather than as a writer of stature, but in Japan his renown remains largely intact. There is a Hearn museum next to his former dwelling in the town of Matsue. Schoolchildren are assigned his books. "Lafcadio Hearn," begins the publisher's foreword to a Japanese edition of Out of the East, "is almost as Japanese as haiku."

Close to two dozen of Hearn's pieces on Japan appeared in The Atlantic between 1890 and 1896, and the archive yields a fair share of both the reveries and the studies. Yet Hearn is often at his most disarming when his atmospheric prose style defies easy categorization, and the shrewd interpreter of cultural otherness merges seamlessly with the excitable sensualist intoxicated by all he sees. Like many of Hearn's chronicles of Japanese life, "At the Market of the Dead" (September 1891) unfolds in a numbered sequence of taut vignettes: in the opening passage a young Buddhist student of his acquaintance inquires whether the foreign schoolteacher would like to have a guided tour of the Bon-ichi market in town, where all the necessary supplies for the summertime Buddhist ceremony, the Festival of the Dead, can be purchased. "Oh, Akira, all things in this country I should like to see," Hearn replies, and off they go to take in the whole nocturnal spectacle. The schoolteacher is particularly entranced by the "ceremony of farewell," when the townsfolk launch "the boats of the blessed ghosts":

Everything has been prepared for them. In each home the small boats made of barley straw closely woven have been freighted with supplies of dainty food, with tiny lanterns, and written messages of faith and love. Seldom more than a foot in length are these boats; but the dead require little room. And the frail craft are launched on canal, lake, sea, or river—each with a miniature lantern glowing at the prow, and incense burning at the stern. And if the night be fair, they voyage long. Down all the creeks and rivers and canals these phantom fleets go glimmering to the sea; and all the sea sparkles to the horizon with the lights of the dead, and the sea wind is fragrant with incense.

In a later set piece, Hearn lingers with customary minute attention on the sights and sounds of the thronging market district, where merchants are selling wares for the festival out of small, lantern-lit booths:

"Hotaro-ni-Kirigisu!—okodomo-shu-no-onagusami!—oyasuke-makemasu!" Eh, what is all this? A little booth shaped like a sentry box, all made of laths, covered with a red-and-white chess pattern of paper: and out of this frail structure issues a shrilling keen as the sound of leaking steam. "Oh, that is only insects," says Akira, laughing: "nothing to do with the Bonku." Insects, yes!—in cages! The shrilling is made by scores of huge green crickets, each prisoned in a tiny bamboo cage by itself. "They are fed with eggplant and melon rind," continues Akira, "and sold to children to play with." And there are also beautiful little cages full of fireflies—cages covered with brown mosquito-netting, upon each of which some simple but very charming design in bright colors has been dashed by a Japanese brush. One cricket and cage, two cents. Fifteen fireflies and cage, five cents.

Hearn was also adept at handling a large topic with a light touch. "In a Japanese Garden" (July 1892) is the deceptively self-effacing title for what turns out to be an extensive commentary on the native conceptions of nature and landscape design, part dissertation, part catalogue, part leisurely ramble. Generations before Western horticulturalists were to recognize the consummate refinements of traditional Japanese gardening, Hearn was already a true believer:

No effort to create an impossible or purely ideal landscape is made in the Japanese garden. Its artistic purpose is to copy faithfully the attractions of a veritable landscape, and to convey the impression that a real landscape communicates. It is therefore at once a picture and a poem; perhaps even more a poem than a picture. For as nature's scenery, in its varying aspects, affects us with sensations of joy or of solemnity, of grimness or of sweetness, of force or of peace, so must the true reflection of it in the labor of the landscape gardener create not merely an impression of beauty, but a mood in the soul.

Here and there Hearn's esteem for the Japanese aesthetic prompts a caustic aside (having observed the exacting discipline of Japanese flower arrangement he remarks, one can only think of European floral decoration as "an outrage upon the color-sense, a brutality, an abomination"), and he occasionally permits himself a pedagogical digression on the ethos of the landscape in Japanese literature and philosophy. Yet much of the article reads less like a lecture than a giddy inventory of everything an attentive visitor might encounter in Japan's garden sanctuaries, from meticulously placed stones and expertly cultivated shrubbery to the happy profusion of living creatures great and small:

Somewhere among the rocks in the pond lives a small tortoise,—left in the garden, probably, by the previous tenants of the house. It is very pretty, but manages to remain invisible for weeks at a time. In popular mythology, the tortoise is the servant of the divinity Kompira; and if a pious fisherman find a tortoise, he writes upon its back characters signifying "Servant of the Diety Kompira," and then gives it a drink of sake and sets it free. It is supposed to be very fond of sake.

As time wore on, Hearn's unalloyed enchantment with the Japanese gave way on occasion to weightier reflections on what he saw as the mixed blessings of the country's newfound prosperity and faith in modern progress. In "The Genius of Japanese Civilization" (October 1895) he pressed the case for a Japanese exceptionalism that in his view stemmed from the "relative absence from the national character of egotistical individualism." This is the side of Hearn most likely to be unpalatable to contemporary sensibilities, inflected as it is with antiquated ideas about race and an overweening attachment to a picturesque, doll-house Japan that embodied all the cultural purity and simplicity that Western industrial society had laid waste.

But if Hearn was no great shakes as a social thinker, the psychology behind his fixed ideas makes for an absorbing case study in fin de siecle angst. That Hearn's idealization of Japan was to some degree a by-product of his animus toward the machine age and its dark satanic mills comes through in the rhetorical thunder and lightning of a passage that contrasts the serenity of the Japanese interior to a nightmare vision of the modern metropolis, a riff that feels like something lifted from the pages of Dickens or Ruskin:

As I muse, the remembrance of a great city comes back to me,—a city walled up to the sky and roaring like the sea. The memory of that roar returns first; then the vision defines: a chasm, which is a street, between mountains, which are houses.... Deep below those huge pavements, I know there is a cavernous world tremendous: systems contrived for water and steam and fire....

And all this enormity is hard, grim, dumb; it is the enormity of mathematical power applied to utilitarian ends of solidity and durability. These leagues of palaces, of warehouses, of business structures, of buildings describable and indescribable, are not beautiful but sinister. One feels depressed by the mere sensation of the enormous life which created them, life without sympathy; of their prodigious manifestation of power, power without pity. They are the architectural utterance of the new industrial age. And there is no halt in the thunder of wheels, in the storming of hooves and of human feet.

"The Genius of Japanese Civilization" goes some way toward revealing the irony—even a certain poignancy—about Hearn's relationship with Japan: here at last the inveterate outsider had happened on a corner of the world that suited his temperament and imagination, only to see much that he cherished wither away as the country made itself over into an imperial power. Even so, there was still enough of the hardboiled journalist in Hearn for him to recognize that his anxiety about the "Occidentalization" of the Japanese had already taken on a tincture of nostalgia:

The charge of want of "individuality," in the accepted sense of pure selfishness, will scarcely be made against the Japanese of the next generation. Even the compositions of students already reflect the new conception of intellectual strength only as a weapon of offense, and the new sentiment of aggressive egotism.... I confess to being one of those who believe that the human heart, even in the history of a race, may be worth infinitely more than the human intellect, and that it will sooner or later prove itself infinitely better able to answer all the cruel enigmas of the weird Sphinx of Life. I still believe that the Old Japanese were nearer to the solution of those enigmas than we are, just because they recognized moral beauty as greater than intellectual beauty.

Such heavy weather is relatively rare in Hearn's Atlantic writings, however. He was more at home lingering over the intimate aspects of everyday life, as he does in "Out of the Street: Japanese Folk-Songs" (September 1896), an engaging little sampler of hayari-uta, or what he calls "the ditties of the day." Waking at daybreak to the strains of washermen "working in the ancient manner" in the vacant lot beside his house, he prevails upon a local literati to write down "the songs of the washermen, and the songs which are sung in this street by the smiths and the carpenters and the bamboo-weavers and the rice-cleaners."

The rest of the short piece essentially amounts to an anthology of Hearn's own free translations, interspersed with a few strands of gloss and annotation. All of the ditties, he discovers, are love songs:

I noticed that almost every simple phase of the emotion, from its earliest budding to its uttermost ripening, was represented in the collection; and I therefore tried to arrange the pieces according to the natural passional sequence. The result had some dramatic suggestiveness... The songs really form three distinct groups, each corresponding to a particular period of that emotional experience which is the subject of all.

The spirit of the project is in keeping with Hearn's lifelong attraction to the inner workings of folk culture, and his habit of turning his foragings in Japan into epiphanies of universal brotherhood:

Thus was it that these little songs, composed in different generations and in different parts of Japan by various persons, seemed to shape themselves for me into a ghost of a romance,—into the shadow of a story needing no name of time or place or person, because eternally the same, in all times and places.

Commentators have surmised that Hearn's last years in Japan were not happy ones. The harsh winters sapped his health; the frequent earthquakes spooked him. Some of his old wanderlust may have returned: he moved several times and eventually abandoned the countryside he'd rhapsodized over in his early essays for better-paying work in the cities, first as an editorial writer for an English-language newspaper in Kobe and then as chair of English literature at Tokyo's Imperial University. It seems that the country he once called an "astonishing fairy-land" at last lost its magic—or at least brought him down to earth. What's clear from his later writings is that Hearn became more and more an elegist of Old Japan, resigned to setting down the chronicle of a vanishing world. Toward the end he acknowledged as much: "What is there, finally, to love in Japan except what is passing away?"

Although it's difficult to catch any hint of that change of heart in the last article Hearn wrote for The Atlantic, there's no mistaking him for the same wonderstruck nomad who had declared shortly after his arrival that "The first charm of Japan is as intangible and volatile as a perfume." "Dust" (November 1896) stands out as a striking oddity even in an oeuvre as multifarious as Hearn's: it's another reverie, all right, but an intensely mystical one, a lush meditation on Buddhist spirituality and cosmology that reads like something out of scripture. Hearn's initial curiosity about Japanese religion (Shinto as well as Buddhism) appears to have been of a piece with his general affinity for soaking up exotica in all its most potent forms, but here there are no concessions to journalistic detachment and nothing to suggest that the metaphysical pondering is being done solely for literary effect. The hook for the article is once again the Festival of the Dead; this time Hearn is wandering alone on the edge of town, where he comes upon a group of children playing in the mud near the roadside. Some of them, he notices, are molding miniature gravestones and holding mock funerals for butterflies and cicadas:

The real sorrow and fear of death arise in us only through slow accummulation of experience with doubt and pain; and these little boys and girls, being Japanese and Buddhists, will never, in any event, feel about death just as you or I do. They will find reason to fear it for somebody else's sake, but not for their own, because they will learn that they have died millions of times already, and have forgotten the trouble of it, much as one forgets the pain of successive toothaches. In the strangely penetrant light of their creed, teaching the ghostliness of all substance, granite or gossamer—just as those lately found X-rays make visible the ghostliness of flesh—this their present world, with its bigger mountains and rivers and rice-fields, will not appear to them much more real than the mud landscapes which they made in childhood. And much more real it probably is not.

In later passages Hearn's language takes on greater fervor, rising to the pitch of an Emerson or a Whitman at his most oracular:

Transmigration—transmutation: these are not fables! What is impossible? Not the dreams of alchemists and poets; dross may indeed be changed to gold, the jewel to the living eye, the flower into flesh. What is impossible? If seas can pass from world to sun, from sun to world again, what of the dust of dead selves—dust of memory and thought? Resurrection there is, but a resurrection more stupendous than any dreamed of by Western creeds. Dead emotions will revive as surely as dead suns and moons.

This sounds like a man who has undergone a conversion experience—and in at least one profound sense, that was surely true. Had Hearn not found his way to Japan, he would scarcely merit a footnote in literary or cultural history; he'd be remembered, if at all, as a two-bit collector of esoterica, a penny-dreadful hack, a marginal man of letters with a quarrelsome streak and a quirky name. Instead, following a plotline almost too farfetched for a potboiler novel, fortune handed him a plum of an assignment—capture the vestiges of the storied Japan of yore, at just about the last possible moment before the country makes its great leap forward in sync with the brave new century—and an author's junket turned into an accidental pilgrimage, an odyssey like none other's. One can hear his wonder at it still reverberating in one of the rapturous closing paragraphs of "Dust," which in spite of its cosmic extravagance—or should we say because of it?—offers itself up as the ultimate vagabond writer's valedictory:

I an individual—an individual soul! Nay, I am a population—a population unthinkable for multitude, even by groups of a thousand millions! Generations of generations I am, aeons of aeons! Countless times the concourse now making me has been scattered, and mixed with other scattering. Of what concern, then, the next disintegration? Perhaps, after trillions of ages of burning in different dynasties of suns, the very best of me may come together again.

—David Barber