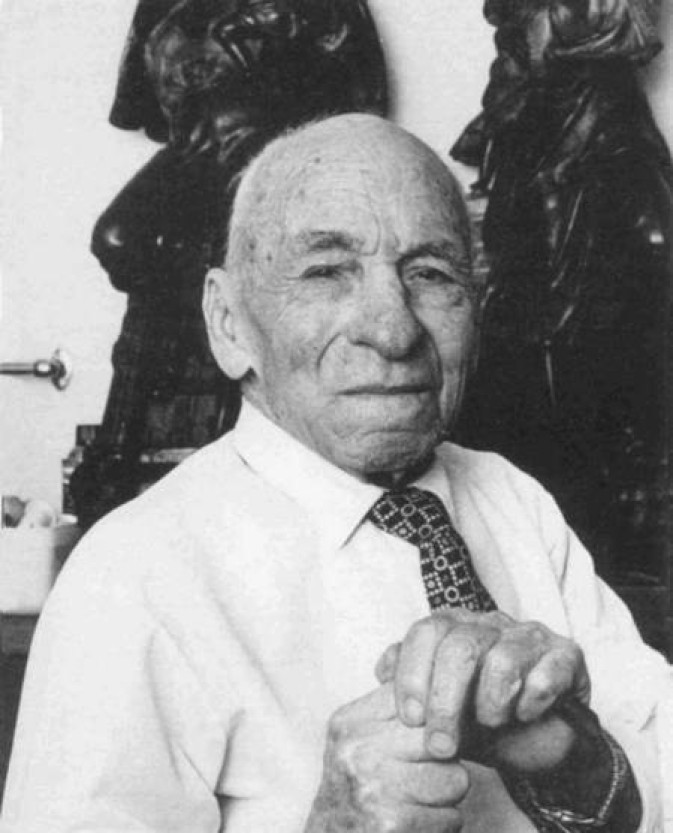

Nicholas Laurantus as he appeared on the front page of the Sydney Morning Herald, 16th June, 1979.

In 1974, on the recommendation of the Archbishop, Nicholas Laurantus was made an Archon of the Greek Orthodox Church in recognition of his many gifts to his birthplace, Kythera, to St Basil’s Homes for the Aged, and to the University of Sydney. The ceremony took place in the Archdiocesan church at Redfern one Sunday evening. The Archbishop, officiating, placed the plain black robe over Nicholas’ bowed head as he stood in front of the congregation, then, when he knelt, invested him with the title of Archon. The church was full that evening, about 500 people being present to witness the ceremony, and after it was over many of them went to the front of the church to congratulate the new Archon, this being the highest honour the Greek Orthodox Church can bestow on the laity.

Some years earlier the Greek government had awarded Nicholas the medal of the ver Cross of the Phoenix the memorative Medal of National Regeneration. The Academy of Athens also awarded him a medal for his efforts to raise the prestige of the Greek community in Australia. Then in 1977 he was honoured by the New South Wales government with an MBE, a distinction which gave him a great deal of satisfaction. Two years later, in June 1979, at the age of eighty-nine, he was knighted.

The front page of the Sydney Morning Herald — the ‘Bible of Sydney’, as Nicholas called it — carried a large photo of the new Knight Bachelor, seated in front of his two cherished statuettes, both hands resting on the head of his walking-stick, as he beamed proudly at the camera. The newspaper made this its lead story, titling it - AN IMMIGRANT ADDS A

KNIGHTHOOD TO HIS TREASURES.

It would be an understatement to say that Nicholas was delighted at the knighthood. He was overjoyed, considering this the greatest of all honours, a priceless reward for a life of quiet achievement. The penniless Greek youth who had set out to prove himself in an alien environment had, one by one, carried off all the prizes. This latest and most-esteemed of all its trophies was the one usually reserved by an Anglo-Australian community to honour its own. His happiness was total.

One of the first to ring Sir Nicholas that Saturday morning in June was his journalist friend, Frances Shoolman. ‘Now it’s your turn to be on the front page of the Herald,’ she said, explaining that she had suggested to the newspaper that they might contact him. ‘You were so pleased when our Annette had her photo in the paper that Father John and I decided it would be nice if you were front-page news too.’ Knowing how much he admired the Herald, it was, they thought, the best present for him.

After that there were many other phone calls to his room, as well as a great many written messages of congratulation, and to each of them Nicholas wrote a separate reply in his firm, flowing hand.

If he was pro-British before his knighthood, he was doubly so the day after. Hilda Heatherington, congratulating him when he called at Lourantos Village, said, ‘Are you going to London for the investiture?’

‘I don’t think I could stand that long flight,’ he said regretfully.

‘Don’t you? But imagine what a marvellous occasion it would be.’ His eyes gleamed and he said eagerly, ‘Tell me about it. Tell me what happens.’ So Hilda described the investiture ceremony at Buckingham Palace while Nicholas listened intently, his eyes shining. Seeing this, she said mischievously, ‘But you don’t want any part of that, do you? You’re not that sort of man.’

‘But I’d love to go,’ he said quickly, refuting her. ‘I really would. Wearing a top hat and one of those coats that trail down behind, and going to Buckingham Palace — oh yes, I’d really love to do that.’ She could see that the picture appealed to his imagination, but nothing more, and they went on talking about the Village.

His investiture took place at Government House, Canberra, on Wednesday 22 August. Nicholas invited three guests: his niece, Thalia Karras, holidaying then in Sydney, and the Kapetases. At first the gentle young priest was reluctant to accept, suggesting it might be better if Nicholas took someone else who was closer to him. ‘I have nobody else,’ said Nicholas firmly.

On the morning before the investiture he was very excited when Thalia called for him at the Masonic Club where they were to meet the Kapetases, who had offered to drive them to Canberra. Thalia hoped that the trip would not prove too much for him but said nothing as they got into the priest’s Holden and set off.

It was a clear, cold, typical mid-winter day and they enjoyed their drive through the countryside, commenting on its greenness and on the large flocks of dust-brown sheep grazing on the rich paddocks around Goulburn. Passing by Lake George, they noticed the shimmering expanse of water, for so many times, as Nicholas said, Lake George was more of a mudflat than a lake, but this was a good year and the lake was full.

It was afternoon when they arrived in Canberra, driving up to the Kythera Motel where Father John had booked rooms for them. Nicholas, tired by the excitement and the long drive, went to bed early, leaving the other three to explore the city. It was the opening night of a new session of the Federal parliament, so the long white building was ablaze with light. A group of protesters, overcoated against the chilly night, milled around the front entrance, chanting, so Father John drove on without stopping.

Wednesday was cold, clear and sunny. Nicholas was very nervous and rather shaky, so the two women went into his room to help him dress. He had brought his best three-piece navy suit and a dark-blue tie splashed with paler blue, but he had refused to buy a new shirt for the event, muttering that this one was perfectly all right. When Thalia looked about the motel room for his socks, she could find only one. ‘Look under the pillow,’ said her uncle. Puzzled, she did so. Underneath the pillow was the other sock — and inside the sock, his wallet.

With a twinkle in his eyes, Nicholas explained to the two women that many years earlier, when he had been staying at a small country pub, he had put his wallet under the pillow before he went to sleep, as was his habit then, only on this occasion he had left the hotel immediately after breakfast without going back to his room. Later in the morning, when he remembered his wallet and returned to the hotel to collect it, he found that all the bed linen had been changed and there was no trace of the wallet. ‘After that experience,’ he said, ‘I devised this foolproof method of putting it in one of my socks, for there’s no way I can leave with only one sock on’. They laughed, watching him put on the other sock.

He was always a careful dresser. ‘How do I look? Do I look all right?’ he used to say before going out. This particular morning was no exception. ‘Uncle Nick, you look wonderful,’ the women assured him as they left the motel room together.

Father John dropped them at the front entrance to Government House, a white Victorian mansion with a green roof, set in extensive grounds, before parking the car and returning to join them in the crowded hall. Ushers led the visitors to their seats in a long blue and pink room with paintings and big bowls of mixed flowers. Those to be honoured sat apart at the rear.

The ceremony started at eleven o’clock. One by one, as names were called out, their owners went up to the Governor-General, Sir Zelman Cowen, to receive their decoration, leaving immediately after by a side door. At eighty-nine, Nicholas was by far the oldest recipient there, but when his name was called he walked up unhesitatingly, leaning just slightly on his stick, stopped in front of Sir Zelman and knelt on the stool. The Governor-General tapped him lightly on the shoulder with his sword and placed the red ribbon of knighthood around his neck. Sir Nicholas then rose and left the room. ‘He made his exit in a most dignified manner,’ said his niece later. ‘He looked as though he was knighted every day.’ Watching him, full of pride for him, she felt the tears trickling slowly down her cheeks. ‘He looked so old and frail.’

After the ceremony, drinks were served on the lawns outside. Sir Nicholas, proudly wearing his ribbon with the gold medallion, introduced his guests to Sir Zelman and Lady Cowen who were circulating among their visitors in the garden. Then Father Kapetas went off to get the car, for they were expected at the Canberra Hellenic Club at two o’clock for a special luncheon hosted by the Greek Embassy in honour of the new knight.

That night the Governor-General gave a dinner party for the recipients of honours and their partners. As time drew near for his departure from the motel, Sir Nicholas became more and more anxious, watching the clock constantly. He looked well in his dinner suit and bow tie but his niece noticed, with a twinge of pity, that the black suit which he had had for so many years was now a little large on his small frame. Finally Father John drove him off, leaving him at the door of Government House with a promise to return after ten. However, when Father John returned, the function was still in progress, so he stayed in the car, shivering in the chill, damp air, until well after eleven o’clock.

When the guests emerged at last into the misty night, Sir Nicholas, despite his age and the long day, was on top of the world. It had been a splendid evening, he said in answer to the priest’s query, but now he was ready for bed. He added that he had had a most interesting chat with the Governor-General about the Greek course at Armidale. Sir Zelman had been Vice-Chancellor at the University of New England when modern Greek was introduced there in 1968, several years ahead of the University of Sydney. It had been most enlightening to compare the two courses, said Sir Nicholas, stifling a yawn as the Holden headed for the motel.

After breakfast he wrote on his copy of the investiture programme, ‘The happiest day of my life. With me Father John, Mrs Kapetas and my niece, Thalia.’ Then he signed his name with a flourish: ‘Sir Nicholas Laurantus’. It was the first time he had written it. He looked thoughtfully at it for a moment, then, smiling broadly, showed it to the priest who was sitting next to him. ‘Doesn’t it look good!’ The other three agreed. Laurantus then looked around the table at them and smiled with deepest satisfaction, ‘Now — now I can die happy’.

On the way back to Sydney, Sir Nicholas felt hungry so they stopped at a café near Marulan for lunch. Thalia Karras recorded in her diary: ‘Uncle Nick had three plates of pea and ham soup and five slices of bread’.

The knighthood changed Nicholas’ life, filling him with a warm inner glow until he died. Not that he had pursued a knighthood, or even desired it, for he respected it too highly to feel that he, Nick Laurantus, should merit this tribute to excellence. But once he had grown accustomed to this thank-you from the country he loved, the knowledge that his efforts had been rewarded with an equal generosity brought him a deep, lasting satisfaction. He was a happy man.

Text - pages 124-130, Photograph - page 125; Jean Michaelides. Portrait of Uncle Nick. A Biography of Sir Nicholas Laurantus MBE. Sydney University Press, Sydney. 1987.