Background and Beginnings. Chapter 2, of KEVIN CORK's Ph.D thesis.

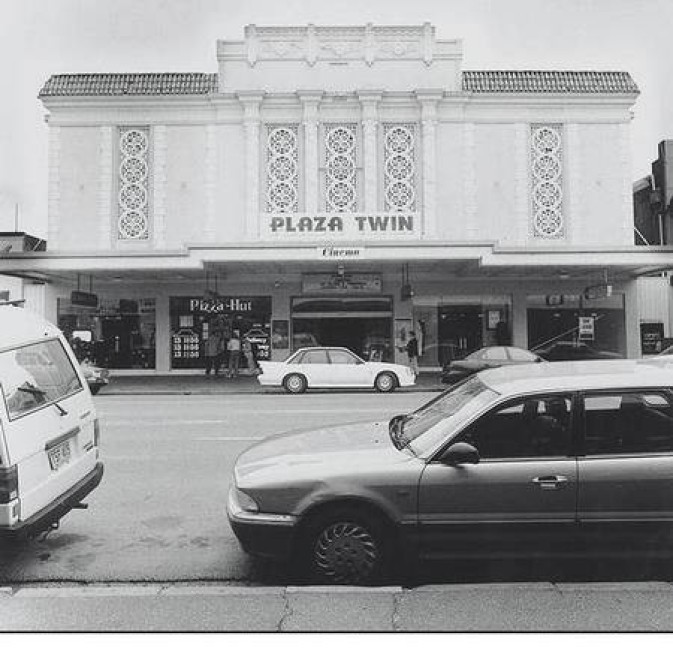

Plaza Twin Cinema, Wagga Wagga, New South Wales.

Photograph by Grant Ellmers, 1996, from, National Library of Australia, collection.

During the 1990's KEVIN CORK undertook extensive research into cinema's in Australia.

Tragically, he died before completing his work, but most of the chapters of his Ph.D Thesis, were completed.

His wife and children have kindly given permission for his work to be reproduced.

Most Australian's would be unaware of the degree to which Greeks, and particularly Kytherian Greeks dominated cinema ownership in Australia - especially in New South Wales.

In Chapter 10, Kevin Cork attempts to provide a comprehensive life history of each of the 66 Greek, and Greek-Kytherian cinema owners he has chosen to be the subject of his study. He manages to follow most until their demise, or return to Greece.

The importance of the Hellenic and Kytherian contribution to Australian cinema ownership and history is clearly demonstrated in Chapt 10, as in all other chapters.

It is difficult to know how to pass on to Kytherians the results of Kevin Cork's important research's.

In the end, I felt that the results should be passed on in the most extensive way - i.e. in full re-publication of Chapter's.

All other chapters have already been submitted to the kythera-family web-site.

Other entries can be sourced by searching under "Cork" on the internal search engine.

See also Kevin Cork, under People, subsection, High Achievers.

CHAPTER 2 - BACKGROUNDS AND BEGINNINGS

"...like an uninvited child, abandoned by its natural mother on the shores of a great but strange country. This country adopted the child but had no wish to observe responsibility of adoption. Greece on the other hand showed little concern for her migrant children."

The history of Greek-speaking people is inexorably linked to migration. Since ancient times, they have migrated to new lands where they have sought improved living and economic conditions. In those far-distant times, it was not only adventurous individuals who migrated, but city-states were known to have established new, far-removed towns in order to unburden themselves of surplus population and increase their own trading potential. As the centuries passed, the land that is now known as Greece came to experience many conquerors and its people suffered in various ways under their oppressors but it was not unusual for young men to travel to other countries, earn sufficient money to return home and rebuild the family home and clear any debts.

After a long and difficult struggle against its Turkish overlord, Greece became an independent nation in 1830. For much of the next century it sought ways to increase its territory and bring more Greek-speaking people into its realm. The political uncertainty that emerged within the new kingdom did little to improve its economic situation and many people lived in poverty. As the twentieth century advanced, Greece continued with its struggle to enlarge its borders and the numerous military engagements it undertook did little to create stability within the region. For example, the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913 were, in part, a catalyst for World War I. Post-war instability in Asia Minor came to a head in 1919 when Greek forces occupied Smyrna (an important Greek-speaking city) on Turkey's Aegean coast but were driven out a few years later by the Turks with appalling losses. An exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey was attempted in 1923 but the problem was further complicated by those "who had fled from Turkey as refugees and [the Turkish] policies of indiscriminate expulsion." The upheaval of population around that time saw an estimated 1,400,000 refugees from Turkey, Bulgaria and Russia move into Greece which exacerbated existing economic problems.

To comprehend why Greeks emigrated in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, one must first appreciate the conditions in which they lived. Essentially, Greeks immigrants to Australia came from islands, coastal towns and inland villages and had what can be best described as a "peasant" background. Price defines this term as coming from a labouring class without urban occupations. Generally speaking, their homeland was limited to "great tracts of rugged country interspersed with small fertile areas sheltered in some relatively small valley, basin or bay." The 'garden' method of agriculture was used because of the fragmentation of cultivatable plots of land and people kept poultry and associated livestock to supplement their livings. For many people, it was little more than a subsistence type of existence. Local markets developed into more than places where produce was sold or exchanged. They served as social gatherings. On the mainland and larger islands (eg Kythera and Lesbos) villages varied in size from large to small hamlets comprising a few houses. As well, there were the wider, more scattered communities with isolated homesteads. The larger settlements developed over the centuries because of banditry, piracy and war. The first characteristic of this type of settlement is its high population density. (For example, Kastellorizo at the turn of the century had over 8,000 people "squeezed into an area little more than one-tenth of a square mile". In comparison, the island of Kythera, between 1890 and 1940 contained over 100 small villages of less than 100 inhabitants, and its capital in 1928 had less than 1000 inhabitants. The second characteristic of close communal life is that small communities provide the services of cafes, inns, markets, church, communal clothes washing, etc which give rise for social intercourse. Local customs and traditions arose in part due to the lack of communication between settlements. This takes into account the lack of twentieth century inventions such as wireless and cinema in the small villages and hamlets. (On Kythera, for example, it is believed that a travelling picture show man visited the island once in the silent era. There has never been an established cinema on the island.) Thus, local gossip, games, dances, festivals and family functions are the mainstay of social interaction. "...the close communal life of nuclear settlement fosters dependence on familiar friends and faces, on habitual activities pursued in company with fellow-villagers and townsfolk, on social customs and traditions peculiar to that particular town or district."

When lack of formal education, a result of their "peasant" upbringing, is added to the economic hardships and the lack of opportunity they faced, it would be safe to assume that many dreamt of a better way of life, one that would give them economic security and a way out of the cycle in which they found themselves. The 1928 Greek Census found that 41 per cent were illiterate and it is quite probable that this figure was a lot higher in the decades before, especially on the islands. Children were often needed to help their parents in order to sustain themselves rather than to attend what schooling might have been available. From the same Census, it was found that 58 per cent of Greek women were illiterate, compared with 24 per cent of Greek men. Prior to World War II, Australia drew many of its migrants from areas of southern Europe where illiteracy was high and this had a profound effect on the types of occupations into which they went. This was especially evident amongst the Greeks.

Australia, on the other side of the world, was completely different to Greece. Linked as we were to the British Empire, there was political stability and compulsory education had been instituted by the turn of the century. The country was developing, there was an buoyancy in the economies of the various states and many saw it as a land of opportunity. When difficulties arose, they were different from those that plagued Greece. For example, rather than severe political unrest, the 1890s saw a period of depression that was heightened by severe droughts.

Overseas prices of Australian staples - wool and minerals - began to decline in 1886 and fell heavily after 1890, while labour troubles increased...The abrupt collapse of Australian credit in London in 1892 burst the land bubble in Melbourne and Sydney and brought down all but one of the Victorian banks in April 1893.

Before the end of the century, the wool industry recovered and wheat farmers expanded and increased their yields. Crown Land was released for settlement as governments began to encourage small-scale farming, railways were extended and country towns benefited. The population was basically homogeneous, certainly with regards to language and customs. Of the 2,323,000 people living in Australia in 1881, just over 60 per cent were Australian-born and 34 per cent had been born in the United Kingdom. By 1901 (at the time of the first Australian Commonwealth Census), the population had climbed to 2,934,091, 77.1 per cent of which were Australian-born and 18.0 per cent born in the United Kingdom. In an attempt to preserve the perceived homogeneity, the trade unions in the late 1880s "...set their faces firmly against assisted immigration of any kind and strongly supported the prohibition of Chinese immigration, since both of these were seen as a danger to the economic position of union members."

The Bulletin magazine, from the time of its establishment in the 1880s, was an advocate of Australia for British-Australians, and the labour movement took a similar stance. In 1897 Western Australia introduced a dictation test that could be used to refuse entry to particular migrants. It was, therefore, understandable when the new Commonwealth Government passed the Immigration Restriction Bill (which included the infamous Dictation Test) and the Pacific Island Labourers Act in 1901, thereby putting into legislation what many British-Australians wanted - a White Australia. The concept came "to embrace more than racial purity and protection of living standards. One extra element was the tendency to interpret the 'white' of White Australia as meaning primarily Anglo-Saxon...A second element of White Australia was associated with ...'Yellow Peril'."

By the time the 1901 Census was taken, a little under 5 per cent of Australia's population had been born outside of Australia (excluding the United Kingdom). Of this, 2.1 per cent had been born in Europe (which included Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Malta and Yugoslavia). Because the southern Europeans had slightly darker skins, they "came to suffer from the predictable fall-out from the stress on colour which the policy espoused in name and in practice..." The general dislike and distrust of these foreigners that was espoused by British-Australians was the result of the low economic position in which the immigrants found themselves, their being a perceived threat to union labour and working conditions and their lack of English language and customs. "Of the thousand Greeks who inhabited Australia towards the end of the 19th century fewer than fifty had had a complete secondary education. Most were unskilled, except in seafaring, and few had more than a smattering of English, picked up from ships' crews." The lack of formal education and the lack of appropriate job skills created difficulties, but having to cope with a new language was "an additional handicap" that many were forced to bear. Unlike the post-World War II years when stress was placed on assisting new migrants with language instruction, those who came before the war were left mainly to their own devices.

In the pre-war period, and indeed early in the post-war years, those newly arrived, even if they had been sponsored by a relative or friend, could, by the constricting factor of the language barrier, only work for other Greeks, or for sympathetic Australians. Usually there wasn't much choice; the lowest of the unskilled jobs was often a starting point...Restaurants, apparently, were a special feature, a mark of respect and testimony that a particular person or family had finally 'made it'.

*Chapter 2 continues...it contains many graphs, tables, and a map, which - to maintain the "lay out" set out by Kevin Cork - requires that it be formatted as a PDF file.

The remainder of Chapter 2 will be made available as a PDF file, shortly.