Bingara’s Living Classroom

During the Roxy Museum Opening celebrations, 5th & 6th April, 2014, the Kytherian dance group will almost certainly stay in an accomodation facility at the Living Classroom Complex in Bingara NSW. This article explains what the living classroom is.

by Suzanne Kyte

Article Project credits

Community group VISION 2020 collaborates with John Mongard Landscape Architects onsite through a process running that has been running over six years.

John Mongard Landscape Architects worked with the northern NSW community of Bingara, to develop strategies for future-proofing their town that can be maintained by residents at little cost.

The township of Bingara lies in the heart of a district in the New South Wales Northern Tablelands, renowned for its natural beauty, livestock and crop production. But like many other rural towns, Bingara faces significant challenges on both global and local levels. In 2008, Gwydir Shire Council engaged John Mongard Landscape Architects (JMLA) to develop a strategy to guide the town’s future development. As part of this process, Bingara residents generated ideas that ranged from main-street improvements to a long-term sustainable agriculture project, and which were further developed through collaborative design processes led by JMLA.

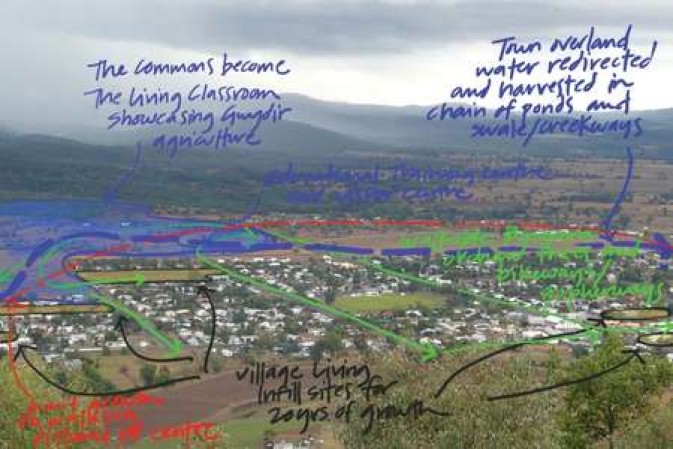

The resulting Bingara Town Strategy outlines an integrated twenty-year framework for building a positive and sustainable future through a series of small and large-scale projects that will dramatically change the town’s approach to food, housing, work and energy planning. By building in opportunities for the community to review and refine options over time, it is hoped that the strategy will remain relevant and accommodate change in line with the vision for the town itself.

Community group VISION 2020 collaborates with John Mongard Landscape Architects onsite through a process running that has been running over six years.

Although many of the initial ideas for Bingara’s future were instigated by local community group Vision 2020, the participation of, and support from, the wider community has clarified local values and needs, contributed new ideas and helped to implement the strategy. As with many of JMLA’s public domain projects, the process began by inviting the community to “setup shop” in a vacant main-street shopfront, where community members could meet to discuss the town’s future. During the course of a week, locals called in to talk about their ideas and those of others, raise issues and brainstorm possible solutions. Visitors to the town contributed valuable insights about Bingara from a tourism perspective.

The town’s riverfront was collaboratively designed and built by the council, John Mongard Landscape Architects, the community and local farmers.

In addition to this, John Mongard and Jacqueline Ratcliffe from JMLA held public meetings and forums, met with local businesses and other interest groups, and held workshops with council staff and other stakeholders. Spending time in Bingara and using a range of consultation techniques helped the pair to learn first-hand about the town, its people and their values, experiences, needs, priorities and capacities. Existing studies about a town can provide valuable information but for Mongard, talking to the community is important because helps to identify ideas and current issues. In this case it was central to developing a meaningful town strategy.

One of the first projects in the town strategy to proceed involved improving the riverfront by building a park. “Each time we did something we had a little mini-engagement project,” explains Mongard. “We’d have a workshop and do a site walk, map out people’s ideas and then we’d go away and draw up a plan.” For the town strategy to be effective, Mongard believes it is critical for it to be realistic in terms of timeframes, capacity and available resources. Like most Bingara projects, the river park was designed and implemented as a collaboration; JMLA devised the plans with community input, local farmers erected the fence, the local council contributed funds and its staff built park elements.

During the first two years, further planning was also undertaken for more complex projects, including improvements to the main street and affordable housing. Another “setup shop” scenario, meetings with council staff and a community forum were staged to discuss the evolving plans and determine how to make them happen despite limited resources. For Mongard, “workshops provide an opportunity to find out what people value … and they act as catalysts for new ideas.” Local skills and knowledge are combined with state and federal funding opportunities to realize projects that could not be achieved any other way.

Work has recently begun on one of the most ambitious projects in the Bingara Town Strategy, the Living Classroom, which is envisaged as a learning centre and showcase for sustainable agriculture.

It will involve transforming 150 hectares of former grazing land adjacent to the town into an integrated and productive farm combining agriculture, horticulture, aquaculture and forestry. Initially the project was conceived without resources attached to it, so although JMLA provided plans, nothing was built. Breaking down the project into smaller activities and obtaining funding has allowed work to begin on the town’s river and creeks to mitigate flooding and recycle stormwater run-off through a revegetated swale system; and roads and paths are taking shape on the site around two new buildings that are already being used for accommodation and training by school and community groups.

Mongard travels to Bingara regularly to work on the project alongside contractors, council workers and volunteers. Being hands-on makes the process more experiential and allows him to modify designs in response to the land.

Collaborative design processes such as this might blur the lines between practitioners and community, but projects like Bingara’s Living Classroom demonstrate an efficient use of local skills, capacity and ideas as well as outcomes that reflect local aspirations. While Mongard acknowledges that it is an exhausting and time-intensive process, he says it is also rewarding. “For me it’s an experiment in seeing whether a country town can reinvent itself in a way [that will make it] more resilient, and I’m putting time into that because I think it’s important.”

Source Landscape Architecture Australia – August 2013 (Issue 139)

http://architectureau.com/articles/bingara-and-the-living-classroom/