Discriminated Against and Forced to Discriminate. Chapter 3 of KEVIN CORK's Ph.D Thesis.

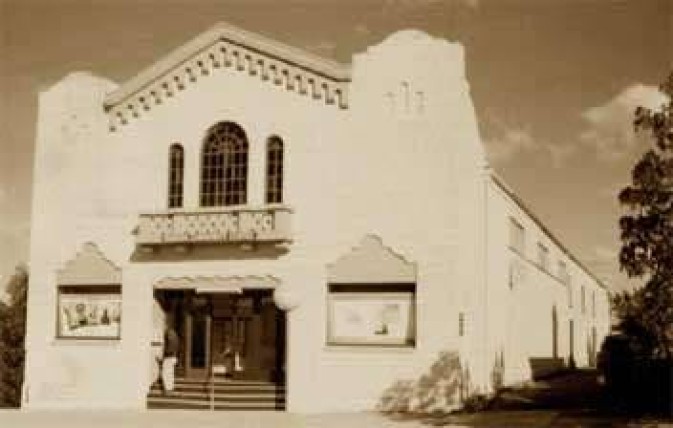

Dungong Theatre, built 1914 redesigned in

Spanish Mission Style in 1930.

During the 1990's KEVIN CORK undertook extensive research into cinema's in Australia.

Tragically, he died before completing his work, but most of the chapters of his Ph.D. Thesis, were completed.

His wife and children have kindly given permission for his work to be reproduced.

Most Australian's would be unaware of the degree to which Greeks, and particularly Kytherian Greeks dominated cinema ownership in Australia - especially in New South Wales.

Chapter 3 of Kevin's thesis is concerned with discrimination against Greeks during the first wave of migration, and induction into discrimation against indigenous Australians during this same period.

The the importance of the Hellenic and Kytherian contribution to Australian cinema ownership and history is clearly demonstrated in Chapt 3, as in all other chapters.

It is difficult to know how to pass on to Kytherians the results of Kevin Cork's important research's.

In the end, I felt that the results should be passed on in the most extensive way - i.e. in full re-publication of Chapter's.

Eventually all Chapters will appear on the kythera-family web-site.

Other entries can be sourced by searching under "Cork" on the internal search engine.

See also, Kevin Cork, under People, subsection, High Achievers.

Chapter 3: Discriminated Against and Forced to Discriminate.

"Sometime ago I wrote you in connection with the Greek invasion

into our little burg [of Bingara]..."

The one thing that has kept Australia homogeneous since 1788 is its English language. In the past, it was expected that immigrants would learn to speak English as soon as possible so as to help them assimilate more quickly. This philosophy was not without its flaws but many of the pre-World War II British-Australian population believed it, as do many today. By the time that the first Commonwealth Census was undertaken in 1901, out of a total population of 3,773,801, there were at least 35 different nationalities represented. Migrants who looked different to the majority of the population and whose command of the English language was slight were the recipients of discrimination in various forms over the years. By far the worst race riots occurred in the gold fields in the 1850s and 1860s against the Chinese. The latter part of the nineteenth century and the early part of this century saw the introduction of dictation tests and other discriminatory laws to prevent the immigration of "unwanted" nationalities. Having dealt decisively with the "Yellow Peril" was one thing, but the "Southern European Peril" was something else.

In 1915 all miners were required to belong to the Miners' Union and abide by wage agreements. This was supposed to ensure that immigrants did not under-cut wages and working conditions. As a result of a large group of Maltese and Greek migrants arriving in Melbourne in 1915 prior to the conscription referendum, a wave of xenophobia set in. Fear of what southern Europeans might do to working conditions while Australian males were fighting overseas, coupled with the vacillation of the King of Greece about where his allegiance lay, led the Commonwealth Government to ban the entry of all Greek and Maltese migrants (except dependent relations). In 1918 on the Western Australia goldfields, brawls and looting broke out because a returned soldier had died as a result of a fight with an Italian. Fifteen years later, the same area witnessed the infamous "anti-dago" riots in 1934 when businesses and houses were destroyed and so-called foreigners were literally "run out of town". Besides the antipathy felt towards non-English speaking migrants by the labour movement, some members of the Returned Soldiers and Sailors' League were quite prepared to "press matters to the extreme". Such was the case when Greeks tried to build a theatre at Bingara in 1934. It really has been a case of what we didn't understand, we feared and, as a result, often took a negative approach to the whole matter.

Writing in 1992 about the acceptance of Greek migrants by Australians, Alexakis and Janiszewski stated that "...Melbourne geographer, J.S. Lyng, writing during the early 1930's...described the Greeks as 'the least popular foreigners in Australia'..." With their limited employment opportunities,

...problems of acceptance by the host society, particularly one which had officially adopted an openly racist immigration policy (the Alien-Immigration Restriction Act of 1901), were evident. Other than the union restriction concerning the employment of foreign labour, xenophobia was often expressed in the form of name calling, restricting the language spoken in public solely to English and even physical abuse.

Assimilation for Greeks was difficult before World War II and the writers cite several examples of pure, unabashed xenophobia. One lady recalled her mother being rebuked by a passenger for speaking Greek on a tram. Another example occurred in the 1930s when a Greek winner of an eisteddfod was publicly shunned "...by not being presented with his award in an open ceremony with the other prize winners".

Perhaps the most frightening demonstrations against Greeks took place in 1915 in Newcastle and Sydney. By December 1915, Greece's neutrality was in question and press reports suggested that Greece's King Constantine was allegedly sympathetic to Germany. The situation fermented and, on 13 December, a 600-plus mob (mainly soldiers on leave) "held sway in the city [of Sydney] last night, and for a time took possession of portion of George-street, bombarding several shops with blue metal and lumps of concrete." Among those shops targeted were Michel Casimaty's oyster saloon (563 George Street) and Seros Bros' Original Candy Kitchen (564 George Street). It was put about that the reason for this "impromptu" action was that news had reached the soldiers that one of their lot had died as a result of injuries sustained in an altercation in a Manly fruit shop. Subsequent court cases saw a number of soldiers and civilians charged and fined for riotous behaviour. It was taken in evidence that

...the men who took part in the riot appeared to have had it in their minds for several weeks. They tried to bring an outbreak to a head in the city on Saturday night, and again on the following night, but the efforts of the police frustrated their plans. On Monday night, however, they carried out their plan in a manner which was evidently satisfactory to themselves. About 500 soldiers, assisted by 200 or 300 citizens of the larrikin class, were responsible...

Bearing in mind that a similar riot had occurred in Newcastle on the previous Friday evening (11th), it is difficult to believe that the Sydney action was not orchestrated. The day after the riot in Newcastle, military and police endeavoured to maintain peace and most Greek shops were shut and barricaded.

The Greeks of the city held a meeting yesterday [Saturday], when they claimed that they were law-abiding citizens. Some of them said that they were naturalised subjects...Since the war started the Greeks here have contributed liberally to the patriotic funds. Friday night's demonstration has been condemned by all sides.

Regardless of their law-abiding ways and contributions to patriotic funds, the Australian Greeks were still looked upon with doubt. The following year, all "aliens" (including Greeks) were required by law to register their presence in Australia. So that their movements could be monitored, they were expected to report to the police station on arrival at their new location.

In some of her early works, well-known English crime writer, Agatha Christie allowed some of her characters to air their xenophobic views. It is reasonable to assume that she was presenting views held at the time, and one may conclude that similar feelings were held in both England and Australia. The following are examples of this. "But Bella could not be regarded with complete approval. For Bella had married a foreigner - and not only a foreigner - but a Greek. In Miss Arundell's prejudiced mind a Greek was almost as bad as an Argentine or a Turk." And, "Any name's good enough for a dago," he remarked..."I like to see your righteous heat, James, but let me point out to you that dagos will be dagos..."

In the course of interviewing and corresponding with the members of the subject group for this thesis, it was found that many experienced discrimination, albeit in varying degrees. Recalling the 1930s when he worked for Greek-born Peter Limbers at the Theatre Cowra, British-born Harry Armstrong said, "...that was the time when no Greeks were really popular. There was a lot of racial prejudice then...Greeks were called 'dagos' and the Greek shops were called 'the dagos'." The poignant side to this discriminatory attitude was expressed by one interviewee. Of Kytheran parents, and speaking for Kytherans, he said that they wanted to be liked and to be recognised as people of merit. They had a deep desire to be seen as good in people's eyes. Hence they strove to honour debts, to create good impressions, and, when time permitted, to be involved in civic activities. Their general lack of formal education was reflected in their tendency toward shyness. From speaking with those born in other parts of Greece (or their descendants), what was said about the Kytherans could apply to all. During the course of research, not all of the exhibitors or their descendants made reference to discrimination. Those who did spoke openly about it. For some, it was old history and of little importance to them now. For others, this was not the case. It was also noted that there seemed to be a change for the better after World War II, which is supported by Alexakis and Janiszewski in their 1992 book.

Examples from the Subject Group - Before World War II

Growing up is never easy and for some of the Greeks, who came as children or teenagers, they experienced racist taunts and jibes because of their lack of English and knowledge of local customs. Nicholas Andronicos experienced this at Moree and he found it easier not to attend school, although his father wanted him to go. Emmanuel Conomos arrived in Walgett in 1919 and was introduced to a 'townie' by his brother Lambros. "When I got there...one fellow asked 'What's his name?' He said 'It's Emmanuel.' 'Oh,' he said, 'it's too bloody hard. Call him Hector.'" The name stuck and acceptance came gradually. George Hatsatouris only attended school once at Port Pirie in 1919. Even though, at the time, there were a lot of Greek people working at the smelting works, George recalled, "The [Australian] kids wouldn't accept you...They don't help you. They would laugh every time you speak, they don't come near us, to help in those days."

Even those born in Australia to Greek-born parents often found that their parents' ethnicity hampered their acceptance. Peter Katsoolis (born in 1927) wrote "It was the same with our family and we were all subjected to the ignorance of people with narrow upbringing." George Nicholas experienced no problems while his family lived in Merriwa. This, he believed, was because it was only a small town and his father, who ran the cafe, garage, picture theatre and ice works, had become well-respected over the years. When the family moved to Newcastle in 1940, George received racist taunts while at school there. Growing up in Cobar after the war, Chris James' son and daughter "experienced the wog and dago bit". At the time, there was only one other Greek family in the town and a Chinese market gardener. At the school, George and Maria James were the only ones whose parents were of non-British-Australian origin. At Gundagai, Arthur Johnson was the brunt of racist taunts for most of his school days. It was not until he started to play in the University of Sydney Rugby team in the late 1950s and brought those skills to the aid of the local Gundagai football team that he started to be accepted. Like Cobar, there was only one other Greek family in town. At Walcha, Philip and Helen Lucas' children experienced similar taunts while at school. There were only two other Greek families in the town. Con commented that, as a result of the racist remarks, he sought to educate himself about his Greek heritage and found that there was a lot to be learned and enjoyed.

Two Australian-born interviewees commented that they did not have any problems about their Greek inheritance. One stated that this may have been due to the fact that he was permitted to bring a friend of his own choosing to his father's picture theatre each week. The other said that he "was a bit of a rebel at school" and this endeared him to other children. He also noted that his father was naturalised in 1905 because he "didn't want to be seen as Greek".

Another Australian-born used persuasion to overcome the taunts of a particular boy during the early 1940s. She informed him that, since her father ran the picture show, she would see to it that the boy would never be admitted unless he stopped the name-calling. Seeing the error of his ways, the boy ceased the taunting. Such was the power of the silver screen in those days!

Greek-born adults experienced discrimination in various ways. Just before World War I began, Jack Kouvelis wanted to marry an Australian girl, Blanche Cummins. While it was considered important that foreigners assimilate, and intermarriage was probably the best way to achieve this, British-Australians did not readily accept the idea of intermarriage, especially with southern Europeans. Mr Cummins was not impressed about his daughter wanting to marry a Greek and so Mrs Cummins brought her daughter to Sydney for the wedding to take place. Grace Walker married James Simos in 1928 and, according to their son, he supposed that, owing to prevailing attitudes, Mr Walker "might not have been too happy about it." Leo Spellson married an Australian girl, Edith, in 1937. While her family did not mind, it "was not approved of by the average Australian in those days." John Tzannes recalled that, during the mid-1930s, he used to visit a Greek carpenter employed by a shop-fitting firm. The Australians worked together, but the Greek worked by himself in a room at the back of the premises. At Wee Waa, Georgina Comino noted a tendency towards racist remarks but commented that it was not only directed at Greeks. The Italians and Chinese in the town also received them.

For Anastasia Sotiros and her daughter at Lake Cargelligo, prior to World War II their "social life seemed to revolve just amongst the Greek people themselves." The families of a number of Greek cinema exhibitors relied on other Greek families in towns where they lived, or in nearby towns, for their socialising. Lack of language and social constraints forced them into this situation. At Lake Cargelligo, there were four Greek families, two closely related. Often, family members would 'promenade' of a late Sunday evening down the street to the lake. "That was their social time." Sometimes, they went on picnics. After the cafes had closed on Sunday evenings, they got together "...in the lounge room in the Monterey Cafe and [played] cards." Although they mixed with Australian people at the cinema, it was not until the daughters grew up and made friends at high school that non-Greek people came to the Sotiros' home. At Gundagai, Arthur Johnson could not recall a time when his family was invited to a British-Australian's home for a meal. They socialised with the town's other Greek family and also travelled to visit relations at Tumut (Stathis family), at West Wyalong (Bylos family), and at Narrandera (Nicholas Laurantus and family).

As already expressed, what we do not understand, we fear and enmity may have been aroused by strangeness of customs, especially those related to the culinary arts. While the Greeks had to cook Australian-style meals in their cafes, in their own homes some old customs did not fade away. Jean Michaelides recorded that Australian-born Blanche Laurantus used to try to cook Greek-style food for her husband, Nicholas, and she also recalled the reactions of locals to the cooking of Sophia Johnson at Gundagai.

When she inserted slivers of garlic into a leg of lamb for roasting, they were horrified. 'Not that smelly stuff,' they exclaimed. 'You'll spoil the taste of the meat.' And when, one evening, she heated olive oil to fry some pieces of fish, they became genuinely concerned, hastening to explain 'that oil's not for cooking with, you only use it on babies when they get nappy rash.' Word quickly went around Gundagai that the new Greek lady knew nothing about cooking and would undoubtedly poison herself and her husband...

Arthur Koovousis, who arrived in Australia in 1949 and lived with his brother at Bingara, said that "In the 1950s, racism [was] still prevalent." They were simply referred to as "the Greeks" by many. Living in Boggabri in the 1950s, Peter Kalligeris recalled that there was "...some racism, but that was long ago now." During an interview in 1995, George Hatsatouris remarked that "...nobody would dare speak out of place to me...I could put them in their place."

Although a number of people did not mention discrimination in their interviews or correspondence, one claimed that he experienced none. Anthony Peters wrote that he was "treated well by all members of the Australian community...[and] has not experienced any discrimination." Perhaps the people of Mullumbimby were better adjusted than those in other areas of the state.

To this point, the material presented above has come from the exhibitors or their families. Some might argue that they may have misjudged those living around them or have been too "thin-skinned". During the course of the research, several primary sources came to light that reveal xenophobic feelings towards members of the subject group.

A rare insight into the esteem in which the Hatsatouris family was held was contained in a letter written in 1930 but it also contained a negative element. The letter remained in a government file and was not found until 1996 when the writer was researching for this thesis. In 1930, both local Port Macquarie picture show operators (the Hatsatouris family and Alf Kenna) were being harassed by a policeman into following the so-called letter of the law with regards to their cinema buildings. A local man decided to write to the Chief Secretary on behalf of the Hatsatouris family in the hope of setting straight the situation. From the content and tone of the letter, it seemed that the Greek family was being given undue attention by the policeman for no apparent reason. The writer told how the opposition exhibitor "...never made a single alteration" yet the Hatsatouris family "...were simply pestered by a Sergeant of Police who has since been transferred... Hatsatouris Bros make their place right up to date and [are] really the most generous people in the town but [are] very retiring. So I thought it was about time some one spoke up on their behalf."

In 1944, investigations were made by the Commonwealth Investigation Branch into J K Capitol Theatres Pty Ltd. The company controlled a number of cinemas in the large, provincial towns of Armidale, Inverell, Moree, Tamworth, Wagga Wagga and Young, The investigation was precipitated by a belief that the prevailing entertainment tax regulations were not being followed closely. Prior to taxation staff travelling to various country centres to interview theatre managers, a report was written in which was set out a short biography of the two principals of J K Capitol Theatres Pty Ltd, Jack and Harry Kouvelis. There is a distinct bias against the two men, especially the older brother. Reference is made to such things as his house, family, motor cars ("including a 16-cylinder Cadallac [sic] purchased some years ago from the Mexican Consul"), property and business dealings, and involvement with race horses. He is described in unsavoury terms and it is suggested that he "...has many enemies amongst the Greek community." The report claims that, when Harry arrived in 1923, his passport described him as a cook. "It cannot be said that either, in spite of their wealth, have made any notable contribution to the land of their adoption." (When one considers the beautiful theatre buildings built under the name of Jack Kouvelis and the immeasurable pleasure that they and their cinematic entertainment provided for many people, one may be tempted to say that the investigator made a biased assessment of the situation. It should also be noted that Jack Kouvelis' son was serving with the Australian Army at the time.) Besides the two brothers, three other Greek families are mentioned in the report which claims that none of them had made any "particular contributions to war loans". The final paragraph suggests that an investigation into the affairs of J K Capitol Theatres Pty Ltd would have "a salutory[sic] effect on the Greek community." Whether or not it did, the results of the investigation are unavailable, although the Greek-Cypriot-born manager of Kouvelis' Moree theatres committed suicide as a consequence. In the newspaper report of his death, it stated that "He was regarded as a man of high integrity, and had subscribed liberally to many charitable appeals", and "Both of his sons are serving in the present war."

In the years before television, when someone wished to acquire a licence for a new cinema, it was not uncommon for objections to be raised from various quarters. Sometimes it would be cinema exhibitors in nearby areas. In the case of Hatsatouris Bros at Laurieton, it was from some disgruntled members of the local School of Arts in 1947. A deal had been struck with the committee whereby Hatsatouris Bros would equip the hall with projection equipment, speaker and screen and show films there until building restrictions were lifted (as a result of wartime shortages) and they could erect a proper cinema. The hall's licence to show films would then be transferred to a new theatre, to be built by Hatsatouris Bros, thus keeping out opposition. They had acquired (in partnership with a local man) a block of land across the road "...on which the projected picture theatre is to be built by the Greek, Hatsatouris." A lot of ill-feeling surfaced about the way the School of Arts' cinema licence was being handled, leading to a number of complaints made to and reports made by the Chief Secretary's Department during 1947. One tried to show Hatsatouris Bros in a disparaging way. For example, "Plainly Hatsatouris is running this theatre 'on the cheap' with two boys and a woman." (re Laurieton School of Arts). At the inquiry held into the granting of the cinema licence to the brothers, one local man stated that he had in mind to build a 750-seat cinema in Laurieton. The judge asked him where he was going to get 750 people when there was only about 500 in the area. The Chief Secretary's Department investigated and rebuffed the reports.

Bingara - a case study

In the mid-1930s, in the north-western town of Bingara, a Greek partnership, Peters and Co (ie George Psaltis, Peter Feros and Emanuel Aroney) embarked on an ambitious construction project involving new cafe, shops and a modern cinema at the south-west corner of Cunningham and Maitland Streets. According to the local newspaper, "When completed it will have an equal frontage to both streets, a symmetrical and well-balanced building, a splendid addition to the town's business houses." Peters and Co intended to construct for their own use a shop and large restaurant (22 feet by 85 feet), with seating for 140 diners, a kitchen (14 feet by 26 feet), two cellars, a machinery room (14 feet by 14 feet) where ice would be made and electricity for the new buildings would be generated, and a modern cinema. Above the shop and restaurant would be living quarters. Two additional shops would be built and made available for lease.

What should have been a straightforward enterprise turned into a financial disaster tainted with overtones of discrimination. There were already two cinemas operating in the town, the Old Bingara Pictures and the Regent Pictures. The former was an old galvanised iron shed and the latter was under the control of a local businessman (who was a returned soldier and an alderman) and he used the Soldiers' Memorial Hall. When, in 1934, he learned that a new cinema was being mooted, he set about trying to undermine the project. Firstly, a letter to his parliamentary representative, who was also an old acquaintance.

Sometime ago I wrote you in connection with the Greek invasion into our little burg, & the position now is becoming more acute, inasmuch as they have issued an ultimatum that any of us who are not prepared to bring our businesses up to their end of the town, opposition businesses will be started by them.

...I have no intention of allowing the Greeks to put it over me in this way, so I am endeavouring to get in ahead of them... & I want you...to find out from the Chief Secretary's Department if the Greeks have yet submitted plans to them for a new theatre, & if so have they been passed by that department'

I shall be submitting plans myself during the next few weeks, & I am hoping those of the Greeks will be held up until I can get a start.

The Chief Secretary replied on behalf of the parliamentarian, stating that "...it is not the practice of the Department to disclose particulars of the kind." Having lost that round, the businessman pushed on quickly with the building of his own theatre (the Regent) which opened in June 1935. Unable to withstand the competition from the new Regent, the Old Bingara Pictures turned-up its toes and died. One might be forgiven if one were to assume that the new theatre would also put an end to the Greek proposal. It did not and Peters and Co pressed on. In early 1936, as the Greeks' Roxy was nearing completion, xenophobia flared again.

As you are aware we are having our own little war with Greece in Bingara, & the latest development is that they want us to run our P.&.A. Asso. Ball in their new theatre, & the Committee have decided to stick to the Soldiers' Memorial Hall. Following on this decision they propose to run a stunt in their theatre in opposition to the Ball.

The Greek theatre is not complete, & is certainly not built to the plans and specifications as submitted...

If the inspection is to be done by our local police I would like you to see that this is carried out in such a way that they are compelled to comply with all regulations, but it would be more satisfactory all round if you could see your way to send your own inspector along.

Trusting you will not mind my writing you personally on this matter, for, as you know the maintenance of our Memorial Hall is a vital matter with our league here, & with kind regards...

Round Two also went to the Greeks when the Chief Secretary replied.

...the local Police were instructed on the 11th March to inform the proprietors that the premises may be opened for public entertainment pending the issue of the required licence, provided the building has been constructed in accordance...

You will, therefore, see that the question whether the premises may be used for public entertainment will depend entirely on the fact of the Police being satisfied in regard to the building...

[re the alternate function] ...I am unable to take any action in the matter if the building is in order and the conditions complied with.

The Roxy (sub-titled "Theatre Moderne") opened on Saturday, 28 March 1936, with the owners acknowledging "the wonderful support of the People of Bingara and District whose encouragement enabled us to open this New Modern Building" and thanking "the various Artisans, Tradesmen and Loyal Workers whose efforts and faithful service made the Roxy possible." Then came blatantly racist newspaper advertising by the opposition. From March, advertisements proclaimed the Regent to be "100 per cent Australian, including Ownership, Employees, Talkie Equipment." This continued until the middle of November, by which time the Roxy management was in financial difficulties, having over-extended itself financially on the building project. The Regent Theatre owner was elected Mayor in December 1936, having served in this capacity in 1928 and 1929. According to the report of the opening of the Regent in 1935, he had come to the town "...as a youth, and during his residence had associated himself with every movement for the benefit of the town. He had also served in the Great War...The Mayor (Ald. C Doherty) also paid a high tribute to Mr Peacocke's good citizenship and progressive spirit..."

Within a short time, Peters and Co's financial difficulties led to the mortgagee taking control of the buildings. Psaltis and Feros moved on and Aroney, having to support his mother and two brothers (one going to medical school) in Greece, moved operations to a new cafe in Bingara. The cafe, opposite the Regent Theatre, was called The Regent Cafe and had been built by the Regent's owner.

Examples from the Subject Group - After the War

World War II made possible the entry of Greek migrants into factories and other unionised industries and it increased the profitability of catering and cinema businesses in many areas. When Greece entered the war on the side of the Allies in 1940, a new bond formed between Greeks and Australians. At Walgett, Conomos Bros held a special fund-raising event for Greek Relief. A similar, but bigger affair was organised at Carinda by Theo Megaloconomos. Sadly, much of the bonding lasted only for the duration of the war. The major changes to the social position of Greeks in Australia did not take place until the mass immigration of post-war years when the overall mix of the population altered. The change in attitude towards Greek migrants was commented upon by several of the interviewees: Mrs G Comino (at Wee Waa); Mrs A James and her daughter (at Cobar); Mrs E Spellson; Mrs A Sotiros and her daughter (Lake Cargelligo); Arthur Koovousis (Bingara). Some of these people believed that Australian soldiers brought back with them kinder thoughts and greater respect for the Greek people who had sheltered, fought alongside them and befriended them during the war. Writers, Alexakis and Janiszewski also acknowledge this when they quoted from a story in a 1947 Oberon newspaper about local cafe proprietor, Peter Capsanis who had decided to return to Kythera for a holiday.

Striking Tributes at Oberon Farewell.

Our countries have always been allies, and have fought together in the struggle for the existence of peace loving nations. The bond of friendship has been strengthened through the undaunted spirit of the Australians in Greece. Greece will never forget the Australians, who from 10,000 miles away came to her assistance in the dark hours when she was being overrun by the enemy. That action will be honoured by Greeks for generations to come.

The Aborigines

The previous sections showed that Greek people were often the brunt of both overt and covert discrimination. As cinema exhibitors, the Greeks came into contact with many townsfolk from different walks of life. While the Greeks had their share of discrimination with which to contend, the indigenous population of Australia, the Aboriginal people, also experienced discrimination and this applied in country towns with regards to that seemingly egalitarian place, the cinema. In previous research, the writer found that theatre managers in the years before the 1960s had to follow what was expected of them regarding Aboriginal patrons. Several mentioned that they were unable to ignore the norm. Thus they, who had experienced discrimination, were forced to exercise discrimination towards Aborigines. One can appreciate that exhibitors (from whatever racial background) would not defy local custom. The following information is offered here as a record of the situation in which a number of Greek-born exhibitors found themselves.

The Empire Theatre at Boorowa was really the Guild Hall, owned by the Boorowa branch of the Australasian Holy Catholic Guild of St Mary and St Joseph. While picture exhibition rights were leased to others, the Guild ran dances and other social functions there. When John Tzannes took over the picture business in the hall in 1946, he followed the existing tradition of taking the Aboriginal patrons through a side door and seating them in the front stalls. Even the fact that the building was owned by a Christian religious group did not prevent discrimination against Aborigines.

Some miles out from Lake Cargelligo a mission station for Aborigines was built and they came to town to the pictures. "They weren't allowed to sit on the seats in the stalls. There were these long stools that must have been something like fifteen feet long, and the poor Aboriginal kids had to sit on these wooden stools, right down the front." When asked about their behaviour, the reply was that "They were extremely well-behaved. They were often blamed by the townspeople for desecrating or vandalising the theatre. But mostly it was the Australians." Who made the decision where they should sit? "I think Dad must have realised that he was going to have trouble if he didn't."

Aboriginal patrons at Walgett used to sit in the front stalls but they could also sit in the back stalls if they chose to pay the extra. Seating prices differed between front and back stalls, and downstairs and upstairs in those days. The cheapest seats were front stalls and the Aborigines chose these. According to the former exhibitor, [This section is yet to be confirmed from primary sources.] Walgett was one of the towns targeted by Charles Perkins and his student entourage in February 1965 in an attempt to highlight the plight of Aboriginal people and the way they were being treated. Among the students' activities, the local RSL club was picketed. Conomos Bros' Luxury Theatre experienced its share. On a particular night, the staircase to the dress circle was obstructed by the students. Recalling the night, Emmanuel Conomos said,

...Perkins organised the students...to come up and declare the theatre black. Sergeant Gleeson was in charge of the town at the time and he rang Bourke in case he wanted reinforcements...Anyway, a few of them [students] came along and they stood on the staircase...Gleeson was there and two or three of his men and he said, 'Look, if you fellows remain when the lights come on at interval time, I'm going to put the lot of you in.'..And they remained there. So Gleeson had two Black Marias out the front. He said,' Boys, get on with the work. Put the lot of them in.' I think twelve of them.

The point was made and, consequently, a few Aborigines did go upstairs. However, it did not last as the upstairs seats were more expensive than downstairs.

Audience seating arrangements in cinemas in pre-television times often followed certain structures. Aborigines (if any in town) and children tended to sit in the front stalls, young people usually sat in the back stalls, the more prosperous business people and farmers and professionals sat in the front circle and the back circle was for anyone else who could obtain tickets. While this is a generalisation, it was particularly remarked upon by the son of the exhibitor at the Civic Theatre, Walcha. Seating within that theatre tended to follow this pattern: downstairs on left - poor whites; downstairs on right - Aborigines; upstairs front middle - graziers; upstairs back - middle class; upstairs sides - young workers and teenagers. While his father exhibited racial tolerance, local customs dictated otherwise. Upstairs was perceived as a "white" domain. He recalled one incident when some white Australians sitting upstairs found an itinerant Aboriginal shearer sitting next to them. They threatened to leave but Philip Lucas refused to refund their money because the shearer had paid for his ticket, was clean and neatly dressed, and was not creating a nuisance of himself. A completely opposite incident involved a drunken Aborigine who wanted to buy a ticket for upstairs. When Lucas refused to grant him admittance to anywhere in the theatre, he retorted with "Greasy wog!" and left.

The final example occurred at Goodooga where an action by the exhibitor's wife was seen by the exhibitor as a reflection on himself. Thalia Louran spent the seven years from her arrival in Australia until her marriage living in the city of Sydney where she had no dealings with Aboriginal people. When she went to Goodooga after her marriage in 1957, she was not familiar with local seating habits. One evening at her husband's De-Luxe Theatre, she could not find a vacant seat in the back section so she sat in the front part among the Aborigines. Her husband was perturbed as it was not fitting for his wife to be sitting there in full view of the "white" community and might be mis-interpreted by them. The same lady used to go for long drives into the country as a form of recreation. On one occasion her car became bogged and after an hour or so of being stranded, some Aborigines came along, noticed a "white lady" in trouble and lifted the car free for her. Forty years on, she can still remember their kindness and their smiling faces.

Of course, there was always the fortunate exhibitor who did not have to concern himself about where Aborigines sat in his cinema. Recalling the late 1940s at Yenda, James Katsoolis' son noted that they could sit wherever they chose and that the Regent theatre management "did not discriminate."

Discriminated against, and forced to discriminate, the Greek exhibitors battled on.