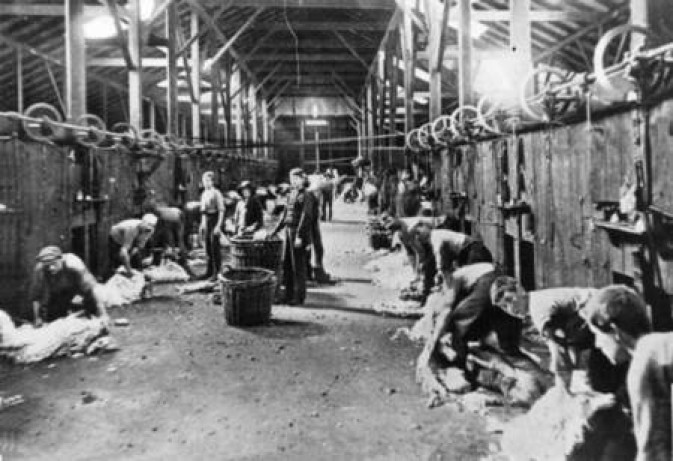

Nicholas Laurantus on Midgeon Station, Narrandera, NSW.

Lake Midgeon Station woolshed, Narrandera. Shearing at the turn of the century, c.1900.

[Nicholas and his brother George had become partners in cinemas, and in Windella station in the period before, during, and after WWII.]

"By 1947 Windella had become profitable and Nicholas no longer had to rely on outside income to survive. The end of the war in Europe meant a greater demand for Australian wool and wheat as the war-damaged countries struggled to feed and to clothe their people. This caused a sharp rise in prices which was pushed even higher by the Korean War in 1950, leading to a boom in wool, with prices at an all-time high of 60 pence per pound, more than four times its fixed wartime price.

As the wool cheques rolled in, Nicholas began to feel much happier about his investment. George, however, had had enough. In 1947 he left Windella, taking his family to Sydney to look for another cinema. But Nicholas was still, as his sister-in-law said, ‘in love with the land’.

In 1949 Lake Midgeon Station came onto the market. Owned by the Austin family, it was one of the best-known properties in the Narrandera area, and one with a long history. Bill Rourke, who was the agent for the sale, suggested to Nicholas that he should put in a bid for it. The price was £98,000 on a walk-out walk-in basis, covering 24,000 acres of land with 12,000 sheep, 200 head of cattle and including the last wool clip, then on its way to Melbourne to be sold.

Nicholas considered it for a week. The long-term prospects were good, he felt, but as usual he had very little cash. He was always a great believer in overdrafts. ‘If you haven’t got an overdraft,’ he used to say, ‘you’re not in business.’ So he rang Elder Smith, a well-known pastoral company in Melbourne, and using his existing properties as collateral, arranged a loan of £56,000. The sale was clinched.

The wool clip, then en route to Melbourne, came onto the auction market shortly afterwards and was sold in the early ‘fifties wool boom'. The proceeds of the sale almost wiped out the loan.

The next ten years were good ones. Nicholas engaged a new manager and they decided to breed their own sheep, using some of the existing merinos as the nucleus of a new flock. When the price of wool started to decline, he began to grow wheat as well, using sharefarmers. Then the newly-discovered myxamotosis virus wiped out the rabbits infesting the hills on Lake Midgeon. They had plagued the previous owner for nearly twenty years.

In 1950, with prices running high for wool and wheat, and a consequent demand for good pastoral properties, Nicholas sold Windella. In 1951, on his three properties, Gum Swamp, Niangay and Lake Midgeon — an area altogether larger than Kythera — he was shearing 28,000 sheep and his wool cheque alone was over £100,000. His income tax went up proportionately.

One day his bank manager met him in the street and said, ‘By the way, Mr Laurantus, there’s £14,000 waiting for you in your account’.

‘Don’t worry,’ said Nicholas, with a cheerful grin, ‘I’ll need some more yet.’ His tax bill of £72,000 was due to be paid. When Nicholas saw the large amounts he now had to pay to the government in annual taxation, he said to himself, ‘Nick, you’d better try to make less and less income and not have this worry’. And it was then he began to look for ways of reducing his tax burden.

Although Nicholas was now a very wealthy man, his lifestyle was unchanged. Still an early riser, he liked to potter about in his workshop at the rear of his house in Larmer Street, experimenting at one stage with a device for self-opening farm gates. At Lake Midgeon he built two good wheat silos, each holding 700 bags, out of riveted iron sheets under a timber shelter. He also made a small metal shed with a rough-hewn timber frame but this was less successful. After a few years it acquired a slightly skewed look, like an early pioneer’s lean-to. A house he built in 1951 in Larmer Street from concrete blocks made on the site with the help of George and John Stathis later developed a large crack in the facade, but it was still occupied a quarter of a century later.

He was always busy, his restless mind considering some new project or other, whether it related to carpentry or finance. He smoked heavily, and always had a cigarette in his fingers. His felt hat pulled down over his eyes against the glare of the sun, he could often be seen walking quickly down the streets of Narrandera — there was no time to walk siowiy — or else passing in a car on his way to one of his properties.

Sometimes he drove out to Lake Midgeon himself, for in 1948 he had bought his first car, a Chevrolet — ‘for Helen,’ he said later — but he never became a good driver. Jim Allen, who worked at Lake Midgeon for many years, winced whenever he saw him at the wheel.

Even after he went to Sydney to live, Nicholas continued to pay visits to Lake Midgeon Station, staying sometimes for a month, a week, or only a few hours. He always liked to work with his hands, even when he was a thin, slightly stooped seventy-year-old. He once climbed onto the roof of the historic Midgeon shearing shed, the largest in the state, determined to repair it himself for he knew that he could do it, and do it unaided. Jim Allen, a quiet countryman with laughing eyes, chuckled at the sight of his frail, elderly boss, hammer in hand, scampering over the galvanized-iron roof ‘like an old possum’.

In 1962 Nicholas employed a new manager, a man of considerable experience on the land, to try to build up the property again, for it had slipped back considerably. John Colhoun and Nicholas soon became close friends, a friendship based on mutual trust and respect. If Colhoun suggested it was time to buy a new harvester, Nicholas made no objection. ‘If you say we need one, John,’ he said, ‘go ahead — buy it.’

Nicholas was very proud of the way Lake Midgeon Station improved under his new manager’s skilful administration. Whenever Nicholas went to the farm to pay bills or discuss plans for the next season, Colhoun would take him on a tour of the property, pointing out the various changes since his last visit. Nicholas listened, but without any close interest, satisfied that the farm was in capable hands once more. He was more interested, Colhoun thought as he took him around the paddocks, in discussing the future of western civilization or the history of ancient Greece. After the tour of inspection had ended, the bills had been presented and cheques made out in Colhoun’s office, Nicholas would take his copy of the newspaper outside to one of the trucks in the sun and climb up into the driver’s cabin to read it. He stayed there, quite happily, for several hours. As the sun moved higher in the sky, he turned the truck, using it, as Colhoun said, ‘like a mobile sunroom’ for the best part of the day.

Nicholas always said that he knew nothing about the land, but as one friend said, he was smart enough to get good managers. A Narrandera business associate commented that Nicholas knew more about the land than he pretended, but whatever the truth, it was certain that he let the experts talk while he listened carefully, asking questions from time to time that were very pertinent.

Jim Colhoun considered him to be an unusual man. ‘He didn’t know

a thing about the technical aspects of farming,’ he said. ‘Nick was purely

a financier, but he did have this love for the land. His knowledge was

such that he could look into the future and say, “Wool’s going to be good,

so we’ll grow sheep”. Or at another time, “Wheat’s going to be good,

so we’ll farm country".

This vision of his, this ability to see ahead into the future, was the main reason for Nicholas’ success as a grazier, as it was in all his ventures. When a journalist once asked him the reason for his success, he merely said, in his modest way, ‘Oh, I’ve been lucky’.

During the years that he lived in Narrandera, Nicholas was invited many times to take part in civic affairs. His leadership qualities and business acumen would have been an asset to any council, and his cheerful personality assured him of a welcome in any company, but he involved himself with only two organizations, the Masonic Lodge which he joined in 1945, and the Narrandera Ambulance Board. Clare was also involved with the Board through her membership of the ladies’ auxiliary, which raised money towards the building of a fine ambulance station at the top end of East Street in 1952. Lady McCaughey of Koonong Station, and Nicholas Laurantus were both substantial individual donors.

A good twenty-four-hour ambulance service for country people was something that Nicholas firmly believed in and which he worked hard to provide during his years of association with the Board. He was vice-president from 1948 to 1952 and then president from 1952 to 1962. In 1960 the New South Wales Ambulance Board awarded him their long-service medal for his thirteen years of committee work.

His association with Lady McCaughey on the Narrandera Ambulance Board was probably the origin of what later became a charming foible. Courteous in his dealings with women, even formal, in his later years, Nicholas often addressed women he knew as ‘Lady . . .‘ Once, when he was in hospital recovering from a broken hip, a Greek friend rang to inquire after his progress. ‘I’m fine,’ said Nicholas, ‘and how are Lady Alma and the little ones?’ Yet, whenever he met the family, he invariably addressed his friend’s wife as simply, ‘Alma’.

Journalist Frances Shoolman later became a good friend of Nicholas and in conversation he addressed her as ‘Frances’, yet letters from him — warm, friendly letters written in his neat, flowing, rather elegant script — always began ‘Dear Lady Shoolman’. Frances, like others, found this an endearing characteristic: ‘He probably felt that “Lady” was more courteous and conveyed more status than “Mrs” or “Miss”, which are everyday words. Perhaps he had heard shearers and others talking about “the missus” and wanted to use a more formal term of address.’

Words always fascinated Nicholas. It was part of his desire, as a former migrant knowing no English, to use the right words, to do the right thing, to fit in. While living in Narrandera and driving out to Windella Station, he would refer to his house in town as ‘my sleeping quarters’. Later, when he lived at the Masonic Club in Sydney, he would often jokingly call his room on the tenth floor ‘my camp’, and any man he approved was usually ‘a good bloke’. A journalist who interviewed him in Sydney once wrote that his talk was ‘liberally sprinkled with “fair dinkums”, “mates", and the Great Australian Adjective — a legacy of years spent in the Outback’. But, like most people, his style of talk varied with his company. Many city friends of Nicholas Laurantus would not have recognized him from that journalist’s description.

Pages 68-70, Jean Michaelides. Portrait of Uncle Nick. A Biography of Sir Nicholas Laurantus MBE. Sydney University Press, Sydney. 1987.