Parthenons Down Under - Chapter 5 [Part A] of KEVIN CORK's Ph.D Thesis.

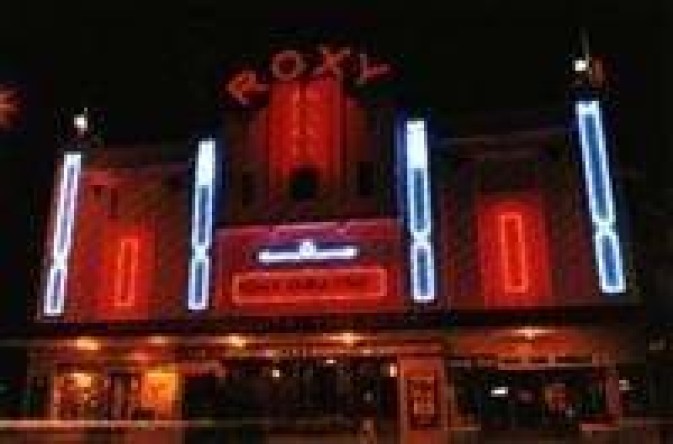

Roxy Theatre at Leeton.

During the 1990's KEVIN CORK undertook extensive research into cinema's in Australia.

Tragically, he died before completing his work, but most of the chapters of his Ph.D. Thesis, were completed.

His wife and children have kindly given permission for his work to be reproduced.

Most Australian's would be unaware of the degree to which Greeks, and particularly Kytherian Greeks dominated cinema ownership in Australia - especially in New South Wales.

Chapter 5 of Kevin's thesis makes the importance of the Hellenic and Kytherian contribution very clear.

In 1995/6, Kevin was involved in the compiling a register of picture theatres in the state of New South Wales for the Department of Planning, Heritage Branch (now The Heritage Office). The register, was the first of its kind in Australia in the hundred years since motion pictures started.

Cinema's in this register are listed in this chapter. Histories of the cinemas's are also re-told.

Kevin was appalled that many cinema's - often unecessarily - had been demolished.

He felt that 6 cinema's in particular had to be preserved. He also felt that these "...buildings (were) worthy of acknowledgment as memorials to Greek-Australian exhibitors" and that they should "..serve as landmarks for the descendants of those Hellenes."

"They are the Strand at Young (1923), the Saraton at Grafton (1926), the Roxy at Leeton (1930), the Rex at Corowa (1936), the Roxy at Bingara (1936), and the Plaza at Laurieton (1959)."

[The picture which heads this section is of course the Roxy at Leeton.

See separate entries in this section of the kythera-family web-site for photographs and history of the Saraton Theatre, and the Roxy at Bingara.]

It is difficult to know how to pass on to Kytherians the results of Kevin Cork's important research's.

In the end, I felt that the results should be passed on in the most extensive way - i.e. in full re-publication of Chapter's.

Eventually all Chapters will appear on the kythera-family web-site.

Other entries can be sourced by searching under Cork on the internal search engine.

See also, Kevin Cork, under People, subsection, High Achievers.

This chapter was too long to post in one piece and Part B follows as the next entry.

Chapter 5: PARTHENONS DOWN UNDER. (Part A).

"The viewpoint of those responsible was not that the town should be worthy of the theatre, but vice versa...In the conduct of such a theatre...they realised that their commitments were of a very heavy nature; but in their unbounding faith in the town they entered into the project with a good heart."

In a recent study, it was observed that there were, generally speaking, five stages of cinema construction in Australia. First of these was from 1896 (when motion pictures were first exhibited) to c1910 during which time local halls, town halls and public ovals were used by itinerant show men. It was not unusual for the films to be one of the acts in a touring vaudeville or concert party. The second stage was when a permanent venue was created. Often, this was little more than a primitive, open air structure. Occasionally a skating rink was converted for use as a cinema. Sometimes the enclosure was roofed thus permitting screenings in all types of weather and allowing for matinees. The third stage saw large shed-like buildings, invariably of timber framing and a combination of flat and corrugated iron, with decorative, pressed metal facades. Sometimes, the exhibitor had enough faith in his location to construct a brick building, but it invariably lacked ceilings and decoration. The fourth stage commenced after World War I when exhibitors built more comfortable, semi-palatial venues. "Through the 1920s this improvement to a more theatrical style is evident. Cinema venues...illustrate the trend to simple classical or semi-classical styling in cement render. Interiors became rendered and lined, frequently above the roof trusses immediately beneath the roof." Simple, applied plaster decorative features were used. As the 1920s progressed, the buildings took on more decoration and the term "Picture Palace" came to mean more than it did when applied to the open air cinemas and large sheds of the previous decade. The final stage "...seemed to be a more active one than that of the 1920s decade. It was conversion, rebuilding and new building in a new style that has caused some difficulty in defining." For some, it could be termed "Moderne" or "Expressionist-inspired". Others refer to it as "Art Deco". In the early 1930s, angular and stylised motifs were used but these gave way to curved and curvaceous forms in the later years of the decade. Three of the stages stated above can be applied to the cinemas built in New South Wales by the Greek-Australian exhibitors.

The relationship between exhibitors and cinema architects has seen little research undertaken on the subject. Some people assume that various cinematic architectural styles were developed and dictated by major city cinema chains (eg Hoyts Theatres). Others might conjecture that overseas models were utilised. For example, in 1927 Stuart F Doyle, Managing Director of Union Theatres, travelled to the United States of America to gain ideas prior to the construction of Sydney's Capitol and State Theatres. While Doyle may have had the money to travel overseas for inspiration, this was not the case for independent and small chain exhibitors. Little is known about their relationship with architects. During research undertaken in the early 1980s by the writer into the life and career of Alfred J Beszant (cinema exhibitor in suburban Sydney), it became obvious that his entrepreneurial flair was ever to the front where cinema building was concerned. From 1910 to 1944 (when the controlling interest in his circuit of 24 cinemas was sold to Hoyts), he was constantly building or rebuilding the cinemas that came under his control. His was the desire to provide comfortable venues and make money and he engaged a number of prominent Sydney architects, including George Kenworthy and Charles Bohringer (both of whom were also engaged by Greek-Australian exhibitors). A number of Beszant's cinemas were substantial picture palaces in their own right (eg Burwood Palatial (1921, extensively remodelled 1932), Strathfield Cinema/Melba (1927), Auburn Civic (1934), Hurstville Savoy (1937)). As the opening night programme of his Civic Theatre at Auburn told patrons,

Nothing that goes for the comfort of its guests has been left out...surroundings that are the envy of every eye...with restful ease and refinement radiating from its every point...TO YOU...the future guests...is dedicated this veritable fairyland, that will leave a lasting memory indelibly printed on your mind.

The environment in which patrons sat to watch films was important. "Environments...are not and cannot be passively observed; they provide the arena for action." Research undertaken in 1994 by the writer showed that many interviewees were aware of specific architectural and decorating elements in their local cinemas. As well, a sense of place regarding the cinemas existed in the minds of many people. For some, descriptions depended on particular patterns of behaviour associated with the building. Patrons dressed up to go to the pictures and, in more important centres, theatre staff wore special uniforms and were particularly conscious of their patron's well-being. Cinemas were places where trouble was not tolerated. "You didn't go there just to make a nuisance of yourself," was one recollection. If the exhibitors wanted to be successful, they had to have a certain amount of empathy with the expectations of the public. While the film programme should be carefully considered, taking into account local likes and dislikes, exhibitors had to pay attention to the environment in which the films were seen. Of course, this varied from centre to centre and depended on economic considerations and attendance potential. In her explanation of the difference between live theatres and picture theatres, Maggie Valentine describes this importance.

Psychological differences also exist between the two types [ie live theatre and movie theatre]. In the movie theatre, ticket buyers take with them only a mood and a memory, which is reinforced by the physical surroundings. In live theatre, the audience and actors interact, feeding off each other and creating a new experience each time. But in a movie theatre, the film is always the same. The experience of moviegoing is shaped by interaction among members of the audience and by the environment itself.

When cinemas were built, local government officials were usually among those who attended the opening nights, such was the prestige associated with the event. During the course of the evening's entertainment, these same men would stand on stage, address the audience (using words that complimented the architect, the exhibitor, the builder and others), and declare the buildings open. Either before or after the compliments, His Worship would invariably relate the importance of the new cinema to the town at large. Below is a chronological selection of examples taken from contemporary newspapers that relate to cinemas built for Greek-Australians.

Young Strand (1923) - The Mayor (Ald Rabbets) noted in his speech that the building "was a great asset as well as an ornament to the town, credible alike to the architect and the builder."

Cessnock Strand (1925) - "Cr. John Brown...congratulated the proprietor on his enterprise in erecting such a fine structure, which would prove a decided acquisition to Cessnock..."

Temora Strand (1927) - "Thanks to the enterprise of the Temora Amusements Company, our town is now the possessor of a picture theatre which is equal to any other on the southern line..."

Tamworth Capitol (1927) - "The Mayor said that...The theatre, both inside and out, was an ornament to Tamworth, and had already proved a splendid advertisement for the town. The many visitors who have had the pleasure of being shown through it have, in every instance, expressed astonishment at there being such a fine theatre in a country town."

Leeton Roxy (1930) - " 'Mr. Conson is to be congratulated on his enterprise in building a theatre which is a credit to the town and district,' said Major Dooley (President of the Willimbong Shire)..."

Wagga Wagga Capitol (1931) - "Alderman Collins said...Wagga possessed excellent public buildings...and now it had added another magnificent building in the best theatre in the country."

Wagga Wagga Plaza (1933) - Alderman Collins...praised the proprietor for the enterprise and genius that had been displayed...By the addition of the Plaza Theatre, he said, another milestone had been added to the record of progress of the beautiful town of Wagga."

Lockhart Rio (1935) - "Cr. J. J. Nolan, the President of the Lockhart Shire...congratulated Mr. Laurantus upon the erection of such a fine building in Lockhart. The new theatre was a splendid one in every way and it was undoubtedly a great asset to the town..."

Moree Capitol Garden (1935) - The Mayor Ald A J McElhome stated that "The theatre...is indeed an acquisition to the town..."

Bingara Roxy (1936) - "His Worship [Mayor C Doherty] congratulated the management on their enterprise, saying that the theatre was a monument to the town and one of the finest buildings of its kind outside the city..."

Walgett Luxury (1937) - "Cr. G.D. Ritchie...doubted whether a better building could be found anywhere and knew that it would stand for many years as a monument to progress and a testimony to the enterprise of the proprietors."

Port Macquarie Ritz (1937) - "The owners of 'The Ritz' are to be complimented upon the erection of such a large and up-todate [sic] theatre, which is a mile-stone in the advancement of the town, and a definitely progressive forward movement. The building is a symbol of the faith in the town and its future..."

Tamworth Regent (1938) - " '...the large sum of money that has been expended and the planning of this new undertaking are appreciated and worthy of the highest commendation.' The Mayor then declared the new theatre open, amid applause."

These comments clearly show that new cinema buildings added prestige to local communities. Emotive words, some might be tempted to say cliches, abound in the remarks: ornament; fine; equal to any; a credit; magnificent; milestone; splendid; acquisition; great asset; enhance the prestige; monument; symbol of faith; worthy. Australians of the 1990s, who are accustomed to bombardment by mass media merchandising, may read these words and dismiss them as being equivocal. Politicians at whatever level of government have been known to be verbose in their remarks, especially at election time. This writer is of the opinion that the men who uttered the above sentences believed that what they were saying was true. Certainly, their remarks were meant to be uplifting and positive but, nonetheless, there was a truthfulness about them. If the building were more modern and better equipped than those in nearby towns, so much the better. In rural New South Wales, the advent of a new cinema could enhance a town's reputation and make residents feel that they had achieved the upper hand on other places. The following comment that hailed the opening of the Roxy Theatre at Cootamundra in 1936 sums up all of this.

He [Mayor, Ald J Rinkin] felt that the erection of this fine building would materially enhance the prestige of Cootamundra as a desirable place in which to live. By reason of its location, the splendor[sic] of its architecture, and the solidity of its construction, the theatre added charm and beauty to the main business centre of the town and would enhance the value of other property in the locality.

While what has been quoted above only relates to cinemas built by Greek-Australians, research undertaken by the writer in past years regarding non-Greek built cinemas reveals similar findings. In the years before television reached country New South Wales in the early 1960s, a cinema was one of the signs of modernity and progress. They were welcomed when first built and they provided entertainment variously for many years. "The motion picture theatre served as a significant architectural experience for millions of people." Yet, for all the accolades heaped upon them at the time of their openings, and having served their communities for years, there is little left in the 1990s of these "monuments", these embodiments of Greek-Australian exhibitors' dreams.

The Buildings

Between 1915 and the early 1960s, Greek-Australian exhibitors controlled at various times 120 venues in 60 towns in this state. Of that number, they were responsible for the construction of 34 (ie 28.3 per cent). In order to show the extensive nature of the towns served by Greek exhibitors, and provide a list of their venues, the following table is presented.

Table 1. New South Wales Cinema Venues Controlled at Various Times by Greek-Australians prior to the early 1960s. (Those in italics were built for Greek exhibitors.)

Armidale Arcadia, Capitol

Barellan Royal

Bellingen Memorial

Bingara Regent and Open Air, Roxy

Bogan Gate Picture Hall, Tolhurst Hall

Boggabri Lyric Open Air, Royal

Boorowa Empire

Carinda Megalo Theatre

Cessnock Strand (1st), Strand (2nd)

Cobar Empire and Open Air, Regent and Regent Open Air

Condobolin Aussie Open Air, Central Hall / Renown

Cooma Victor, Capitol

Cootamundra Arcadia, Roxy

Corowa Rex

Cowra Centennial Hall / Theatre Cowra, Globe, Lyric, Palace

East Moree Theatre and Open Air

Fairfield Butterfly, Crescent

Glen Innes Grand, Roxy

Goodooga De-Luxe

Grafton Fitzroy, Saraton

Griffith Lyceum, Rio

Gundagai Theatre

Harden Lyceum

Hay Federal Hall

Hillston Roxy

Inverell Capitol

Junee Lyceum, Atheneum

Kempsey Macleay Talkies, Victoria

Kempsey West Adelphi/Roxy

Lake Cargelligo Star, Civic

Laurieton School of Arts, Plaza

Leeton Globe and Open Air; Roxy; Roxy Garden

Liverpool Regal

Lockhart Open Air; School of Arts; Rio

Merriwa Astros

Moree Capitol, Capitol Gardens

Mt Victoria Pictures

Mullumbimby Empire

Narrandera Globe (1st) and Globe Open Air; Criterion Hall; Globe (2nd) / Plaza

Nyngan Palais and Open Air

Port Macquarie Empire, Civic, Ritz

Rose Bay North Kings

Scone Civic

Tamworth Capitol, Regent, Strand

Taree Civic, Savoy

Temora Crown, Star and Open Air, Strand

Tenterfield Lyric

Tullibigeal Hall, Public Hall

Tumut Montreal

Ungarie Hall

Wagga Wagga Capitol, Capitol Gardens, Southern Cross, Strand, Plaza

Walcha Theatre, Civic

Walgett Picture Palace, Olympia Pictures, Victoria Theatre, Popular Pictures (School of Arts), Luxury

Warialda School of Arts

Wee Waa Star (1st), Star (2nd) (School of Arts)

West Wyalong Rio and Open Air, Tivoli, Reo Garden

West Maitland Lyceum Hall, Rink Pictures

Woolgoolga Seaview

Yenda Regent

Young Lyceum Hall, Imperial Open Air, Strand

The distribution of where the Greek exhibitors were situated does not follow any particular pattern and the time in which Greek exhibitors showed pictures was not constant. With the exception of three suburbs in Sydney, (Fairfield, Rose Bay North and Liverpool), the Greek exhibitors kept to country areas. Along the North Coast, they stretched over eight centres, from Taree to Mullumbimby. In the Hunter Region, four towns were represented. The Blue Mountains, only ever the home of a few cinemas anyway, had one Greek at Mount Victoria for a very short time. The Northern Tablelands had six towns (if one includes Inverell) with Greek exhibitors. In the North/North-West of the state, Greeks exhibited in 11 towns. It is in this area that Conomos Bros of Walgett "sent out" Peter Louran to Goodooga and Theo Megaloconomos to Carinda where both opened cinemas. In the Southern Highlands, only one town is represented. By far the biggest concentration of Greek exhibitors was in the Southern/South-Western part of the state (including the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area). Greeks ran the pictures in 25 towns in the area. Some of this concentration is, in part, owning to the work of Nicholas Laurantus who, for a time had his own cinemas (Narrandera, Lockhart, Corowa and Hillston), but was instrumental in having his relatives operate others at various times in Cootamundra, Junee, West Wyalong, Tumut and Gundagai. A similar situation occurred on the North Coast where the Hatsatouris brothers operated cinemas in Port Macquarie, Taree, Laurieton, West Kempsey and Walcha. George Hatsatouris' brother-in-law managed the West Kempsey venue (42 kilometres away from Port Macquarie) and Philip Lucas and his wife Helen (nee-Hatsatouris) ran the show at Walcha, 172 kilometres from Port Macquarie.

Just as British-Australian exhibitors engaged the services of prominent Sydney architects to build comfortable venues in order to make money, so too did the Greek-Australian exhibitors. With the passing of time and the loss of reference material, some of the theatre architects have not been able to be identified. Among the architects whose names have been found are some of considerable importance in the design and construction of picture theatre buildings in this state. The theatres built for Greek exhibitors ranged through the period 1915 to 1959.

Table 2. Year of Opening, Towns, Venues, Greek Exhibitors, Architects - 1915 - 1959.

(The number after a theatre's name indicates the construction stage into which it fits. See above for details.)

Year

Town and Name of Venue

Exhibitor

Architect

1915

Walgett American Pic Palace /2

A Crones

Unknown

1918

Young Imperial Open Air /2

P & J Kouvelis

Unknown

1923

Young Strand /4

J Kouvelis

Soden & Glancy, Sydney

1925

Cessnock Strand /4

Narrandera Criterion Hall /4

S Coroneo

N Laurantus

Unknown

Unknown

1926

Grafton Saraton /4 later /5

Notaras Bros

F J Board, Lismore

1927

Temora Strand /4

Narrandera Globe (2nd) /4

Tamworth Capitol /4

P Calligeros

N Laurantus

J Kouvelis

Clement Glancy, Sydney

W Innes Kerr, Sydney

Bohringer, Taylor & Johnson, Sydney

1928

Tamworth Strand /4

Kempsey Rendezvous /4

Merriwa Astros /4

S Coroneo

Mottee Bros

Nicholas Bros

G L Grant, Sydney

Unknown

C Bruce Dellit, Sydney

1929

Junee Atheneum /4

N Laurantus

Kaberry & Chard, Sydney

1930

Leeton Roxy /4

G Conson (Riverina Theatres Ltd)

Kaberry & Chard, Sydney

(G W A Welch of Leeton, supervising architect)

1931

Wagga Wagga Capitol /4

J Kouvelis

Bohringer, Taylor & Johnson, Sydney (G P Turner, of Wagga Wagga, supervising architect)

1933

East Moree Danceland /4

Wagga Wagga Plaza /4

J and N Andronicos

J Kouvelis

H H Court, Moree (built walls, roof, etc 1935)

Bohringer, Taylor & Johnson, Sydney

1934

West Wyalong Reo Gardens /4

C Bylos

Bohringer, Taylor & Johnson, Sydney (G P Turner, of Wagga Wagga, supervising architect)

1935

Lockhart Rio /5

Moree Capitol Gardens /2

N Laurantus

J Kouvelis

Allan & Rowlands, Narrandera

Crick & Furse, Sydney

1936

Cootamundra Roxy /5

Leeton Roxy Gardens /4

Hillston Roxy /4

Bingara Roxy /5

Corowa Rex /5

East Moree Open Air /2

J Simos (et al)

G Conson (et al)

N Laurantus

Psaltis, Feros and Aroney

N Laurantus

N Andronicos

W Kenwood & Son, Sydney (G Mammett, Cootamundra, supervising architect)

L J Buckland, Sydney

Allan & Rowlands, Narrandera

W V E Woodford/e,

109 Pitt St, Sydney

Allan & Rowlands, Narrandera

Unknown

1937

Walgett Luxury /5

Lake Cargelligo Civic /5

Port Macquarie Palatial Ritz /5

Conomos Bros

T Cassim/A Sotiros

E Hatsatouris & Sons

C Bruce Dellit, Sydney

H Helman, Forbes

G N Kenworthy, Sydney

1938

Tamworth Regent /5

J Kouvelis

Crick & Furse, Sydney

1941

Goodooga De-Luxe /2

P Louran

Unknown

1954

Condobolin Renown (remodelled) /5

E Fatseas

Bruce Furse & Associates, Sydney

1955

Taree Civic (rebuilding completed) /5

G Hatsatouris

G N Kenworthy, Sydney

1959

Laurieton Plaza /5

Hatsatouris Bros and B Longworth

Kenworthy, Traill, Arena & Associates, Sydney

(J Arena did the design)

Among those of especial note is C Bruce Dellit whose Sydney War Memorial in Hyde Park was designed in 1929, shortly after he designed the Astros Theatre at Merriwa. A comparison of front elevations of both buildings shows a slight similarity. It would be interesting to conjecture that Sydney's Hyde Park gained from a cinema experiment at Merriwa. Certainly, both buildings have a theatrical element. The Astros was bull-dozed only a few years ago in the name of progress, its designer unknown at the time.

In their early years of cinema exhibition, some of the Greek-Australian exhibitors used public halls (ie the first stage of cinema construction). An early example of this occurred during December 1915 when Emanuel Fatzeus utilised his Lyceum Hall and a nearby roller skating rink in West Maitland for cinematic performances. It was reported that the 1000 "seats are of a comfortable nature, and the electric lighting plant and machinery are on the most improved lines, the biograph being one of the latest Pathe models." J J Ernst was in-charge of the operating box and Misses Dumbrell and Harford provided the music on piano and violin respectively. Fatzeus' employment of British-Australians may have been two-edged: firstly there may have not been any Greek people proficient enough for the jobs; secondly, by employing those mentioned, patrons might appreciate his attempt at integration into the existing society. While Fatzeus was able to use existing buildings for his own purposes until 1917 when his cinema enterprise closed, others used public halls at various times up to the 1960s (for example, Comino Bros at Wee Waa).

It was not unusual for stages of building development to overlap. The second stage involved the construction of two open air venues by Greek-Australians - one in 1915 at Walgett, and the other in 1919 at Young. Success when screening at the Walgett School of Arts in 1915 must have encouraged Alfred Crones (aka Angelo Coronis/Coronces) into constructing the American Picture Palace (variously known as Crones' Picture Palace and Walgett Picture Palace) which opened on Tuesday, 17 August 1915. The local newspaper gave no details about the venue but did state that there was an "extra fine programme" and that the audience was not as large as anticipated owing to the very cold night and the fact that the cinema was open air. The last time it is mentioned in the local press is a short item in May 1916. With that, the first cinema built in New South Wales for one of Greek descent passes into oblivion.

No explanation has been found as to why Fatzeus at West Maitland ceased to screen pictures in 1917. Rather, newspaper advertisements became fewer and his cinema business seemed to fade away. In 1917, only the odd dance at Fatzeus' Hall was advertised in the local newspaper. It is possible that other cinema proprietors in West Maitland managed to monopolise the rental of film product. It may also have been the "alien-isation" of Greeks during World War I that saw his business decline. The son of one German migrant stated that his German-born father, who arrived in Australia in 1911, was forced out of his cinema business by his other partners during World War I because of his former nationality. Patronage at the theatre had dropped and the partners blamed it on anti-German feeling. Crones and Fatzeus may have faced similar experiences and their businesses declined. These were the only two Greeks known to have been showing films during World War I, and no relatives have been found from whom information might be obtained. Thus it is pure speculation about why they ceased exhibiting. Crones moved to Sydney in 1916 and, after a short time, disappeared from the scene. Fatzeus remained at West Maitland until c1918 then disappeared.

The second Greek exhibitors to build in the style of the second stage were Peter and Jack Kouvelis who registered the firm of Imperial Pictures in Young on 2 January 1919. Shortly before this, they were screening films in a hall (Lyceum Picture Hall) in Boorowa Street. In late 1919, they constructed an open air cinema adjacent to the hall. The Imperial Pictures opened on Monday, 17 November and remained open air until 1923 when it gained a roof - "new Waterproof Canvas Theatre". By that year, the adjacent hall had been demolished and Jack Kouvelis was erecting a new cinema on the site. The canvas roof may have been a necessity to ensure continuity of screenings in all weathers. When the new cinema opened on 1 May 1923, the Imperial closed. Jack Kouvelis retained an interest in cinemas, going on to form J K Capitol Theatres Ltd, which operated a chain of country cinemas in New South Wales.

Although the various stages of cinema construction overlapped, those Greek-Australian exhibitors who built skipped the third stage (large barn-like structures with the least amount of comfort for patrons). This occurred because the early Greek builders drew upon the cheaper, second stage for their inspiration even thought the third stage had evolved by the time they were building. By the 1920s, the fourth stage was clearly in evidence in theatre building construction and this was when the newer generation of Greek exhibitors started to build. They knew that, if they wanted to succeed, they had to make their cinemas better than what had been around in earlier stages of construction.

The first of the cinemas to represent the fourth stage was that built by Jack Kouvelis at Young and superseded his adjacent Imperial Pictures. Having failed to persuade the local council to erect a new civic hall (which he was prepared to lease), Kouvelis demolished the old wooden and iron Lyceum Hall and erected a modern theatre on the site. With this, the Greek-Australian exhibitors embarked on the construction of many fine cinema buildings.

There is no clear demarcation line between the end of a stage of development and the beginning of another. While the fifth stage, with its Moderne/Art Deco decoration, was noticeable in the decade after the 1920s, occasionally there were "throwbacks". The way of the world is such that architects are obliged to design according to clients' available finances and expectations. Just as some fine theatres were built during the fourth stage, so too were some fine cinemas built for Greek-Australian exhibitors during the fifth stage. It was not unusual for well-known architects to be engaged (see Table 2), for example C Bruce Dellit, Guy Crick, Bruce Furse, George Kenworthy and Charles Bohringer.

A Fragile Nature of Theatre Buildings

With 120 venues in the hands of the 66 subject group members at various times between 1915 and 1984, one might be forgiven if one were to assume that there is a lot on record about their personal histories and the theatres they operated. This is not the case. Until the writer undertook the interviews and correspondence for this thesis, only one of the group had been contacted, this by Hugh Gilchrist for his Australians and Greeks (Volume 1). The others were surprised that anyone would be interested in recording their work or the work of their fathers. A similar story has emerged in relation to the buildings that they operated as cinemas. Instead of there being representative examples to acknowledge the contribution made by these men to the social, cultural, technological and architectural heritage of this state, we face the reality that nothing has been done to ensure a place for them in The National Estate. It is one thing to classify Union Theatres' Henry White/John Eberson-designed Capitol Theatre in Sydney as a fine example of Australian Picture Palace architecture (although it is a hotch-potch of styles and concepts borrowed from USA, with much of the plaster decoration and other elements being imported from that country). It is another thing to realise that cinemas commissioned by and for Greek exhibitors in New South Wales have not been acknowledged in a similar fashion as worthy of preservation as part of our Greek-Australian heritage. In 1995 controversy raged over the re-development application by the owners of the Mandarin Cinema in Elizabeth Street, Sydney. Aboriginal groups protested because the Australian Hall (the cinema's original name) had been the place where the first national Aboriginal civil rights meeting had been held in 1938. The National Trust, the Heritage Council and Aboriginal groups maintained that the place had significant historical and social importance to the City of Sydney. To those Australians of the future of Greek descent, it is important that Greek landmarks also be established. Part of this should relate to the social, cultural, technological and architectural contributions made by the members of the subject group.

In 1995/6, the writer was involved in the compiling of a register of picture theatres in the state of New South Wales for the Department of Planning, Heritage Branch (now The Heritage Office). The register, the first of its kind in Australia in the hundred years since motion pictures started, is divided into a number of sections. One of them is an alphabetical listing of known venues, divided into Sydney city, Sydney suburbs and NSW country towns. Using information from the Register regarding the 120 venues operated at one time by Greek-Australian exhibitors, several interesting points may be drawn regarding their legacy. Only 7 of the cinemas are still operating. One of them is in a community hall and was only operated for two years by a Greek-Australian. Two are closed, their futures uncertain. Seven have reverted to their original status, as a community halls. Thirty-six have been adapted (in varying degrees) to take another type of business. While some have retained bits of their cinematic features, others have been completely gutted and only retain their facades. The category most often found is "Demolished". Out of the 120 venues operated, 69 (ie 57.5 per cent) have been demolished. It should be kept in mind that this situation has occurred over a long period of time. Demolition of cinema buildings is an on-going occurrence, whether by fire (18 cinemas) or purposeful intervention (51 cinemas). The latter category acknowledges that, besides obsolescence, exhibitors vied with each other or endeavoured to keep abreast of new developments in technology. For example, Kouvelis' Imperial Open Air Theatre at Young outlived its usefulness within a few short years and was superseded by his new Strand in 1923. The Notaras Bros' Saraton Theatre at Grafton was extensively modernised in the 1930s, turning the theatre from a Stage 4 type of construction into a Stage 5 type, and giving Grafton a theatre of which it can still be proud some sixty years later. In doing so, all vestiges of the former silent-era cinema, except for the facade, were swept away. After the coming of television, it was not uncommon for cinema buildings to be perceived as obsolete, "a thing of the past", and not worthy of retaining. This sub-category of post-television demolitions accounts for 29 venues.

What makes the demolition of these buildings (for whatever reason and in whatever time) regrettable is that it is done for the sole purpose of replacing it with something which is considered to be more modern, rather than utilising the extant and thereby maintaining its "place" within its community. Buildings, that might have been retained as representatives of a particular architectural style or for their social history, have disappeared. Even the replacing of an older style of cinema with a newer one has meant a loss of architectural, technological and social history. While realistically it is impossible to retain everything, the alternatives should be more often considered. Yet, of the 34 cinemas built for Greeks in this state, and it is from this group that suitable landmarks to mark their contribution to our social history should be found, 16 have been demolished, 15 have been altered to various degrees, and only 3 remain relatively intact. From the 18 extant buildings, there is a limited range from which to choose if a selection were to be made to acknowledge the contribution of the Greek-Australian exhibitors to the social, cultural, technological and architectural heritage of this state.

The following examples show just how easy it is to demolish a building if one is intent. While an outhouse is one thing, a large, important public building is something altogether different. If the following cinemas had been extant at the time the Movie Theatre Register was compiled in 1995/6, each would have been classified as Category 1 (ie worthy of retention).

Firstly, the case of Jack Kouvelis' Capitol Theatre at Tamworth was little more than crass commercialism. In 1984, locals believed that the owner of the building intended to restore it and sympathetically convert it into a venue for live and film presentations. The local historical society supported the project and the National Trust was supposed to be "on the verge of classifying the theatre". What was not known was that the owner, while giving the impression that he was prepared to undertake the work, was actually negotiating with the local council to purchase the property. At dawn on 5 November 1984, a wrecking crew moved into the theatre and, despite protests from locals, the theatre was reduced to rubble. Police were not empowered to stop the work and both the owner and the Mayor were out of town and could not be contacted. Local newspaper headlines attacked: "Council Plotted its Ruin" (6.11.1984); "Demolition Hurts Many" (6.11.1984). Local high school students, angered over the loss, demanded answers from council but debate was gagged at the meeting they attended on 27 November. Two days later, Tamworth Council decided to purchase the empty site. The theatre that was reputed to have only one rival in the state when it opened in 1927 (that being Sydney's Prince Edward Theatre) was reduced to rubble in an insidious manoeuvre to gain a car park. "And the ATHS [Australian Theatre Historical Society], the National Trust, the Heritage Council, the Tamworth Historical Society, the local press and the people of Tamworth were all taken completely by surprise."

If the Capitol was a good representative of the 1920s "Picture Palace" style, then James Simos' Roxy at Cootamundra was an excellent example of 1930s Art Deco. On 6 October 1992, its then-owner, the adjacent RSL Club, commenced demolition.

Paperwork which could have saved Cootamundra's Roxy theatre from demolition this week was lost within the NSW Department of Planning in 1985, the National Trust claimed yesterday. A report in that year recommended the 56-year old theatre be listed as a heritage building. The recommendation was set to be passed by the then minister but its paperwork was lost by bureaucrats.

The President of the NSW branch of the National Trust was reported as saying that "the demolition of the theatre was just another 'disaster' for conservation in the State." Sadly, he was merely lamenting its architectural loss, rather than focusing on the broader issue of Greek-Australian cinema heritage. What makes the situation even more ludicrous is the reason given in the newspaper for the demolition. "Representatives of the National Trust were amazed to discover last week the Cootamundra Ex-Servicemen's and Citizen's Club was to demolish the theatre because they believed it had been registered as a heritage building." When the Minister for Planning, Robert Webster was asked to place an emergency protective order on the site, administrators in his department "stated that it was 'uneconomical' to save the Roxy...[he] was also told that there were a number of art-deco theatres, like the Roxy still in existence..." Thus the Roxy, "one of a few buildings which still maintained its art-deco features both with its facade and internal furnishings" was reduced to rubble to make way for - a car park!

At Merriwa, Nicholas Bros' Astros Theatre of 1928 was unceremoniously demolished in 1993, with the blessing of the local council, by a potential developer who had allowed the property to fall into disrepair in preceding years. The local historical society was unaware that C Bruce Dellit had designed the theatre. The Astros was his only building in this genre left intact. Now, four years later, there is still "an empty block of land right in the middle of the street and it looks a bit like a missing tooth!"

Sometimes, it has not been the case of an "outside" developer. Hatsatouris Bros' Palatial Ritz Theatre at Port Macquarie was an elegant Art Deco showpiece built in 1937. In the early 1970s, the family retired from the business and leased the theatre to another exhibitor. By the early 1980s, economics had come into play. As a single screen cinema, it was too large and film company politics (involving long runs in order to secure first release films) meant that it was no longer viable. One can sympathise with Peter Hatsatouris who, for sound economic reasons, demolished the Ritz in 1982 and constructed a twin cinema inside its shell. However, it was in no way a sympathetic conversion and all was lost of the original Ritz except for a small part of the facade.

Where Are They Now?

The following Greek-built cinemas have been demolished: Cessnock Strand (2nd); Cootamundra Roxy (#); East Moree Open Air; Goodooga De-Luxe (#); Leeton Roxy Gardens (#); Merriwa Astros (#); Moree Capitol Garden; Port Macquarie Palatial Ritz (#); Tamworth Capitol (#); Tamworth Strand; Taree Civic (#); Wagga Wagga Capitol (#); Walgett Luxury (#); Walgett Picture Palace; West Wyalong Reo Gardens; Young Imperial Open Air. Of these, the ones marked with (#) would have qualified for a Category 1 classification in the Movie Theatre Register for various reasons. The Walgett Picture Palace may have qualified because it was the first Greek-built cinema in New South Wales and could have been a representative of primitive open air cinemas.

The following 15 buildings have been adapted to other uses and the extant cinematic elements in each varies. Part of the Bingara Roxy is used as a restaurant, although most of the building is intact, as are the adjacent shops and residence above the corner shop. Condobolin Renown (remodelled in the mid-1950s) had a video shop and restaurant (both closed) in part of it, but its auditorium remains intact. Corowa Rex retains most of its cinematic features and its exterior and is in use as a shop. East Moree Danceland Theatre retains part of its facade but the interior has been divided into shops. While alterations were made to the Hillston Roxy in the 1950s, it retains much of its original auditorium decoration and is currently used for storage by a stock and station agent. Junee Atheneum has become the Jadda Centre for community use and, according to a local council staff member, has suffered over the years. Kempsey Rendezvous/Macleay Talkies has been adapted so well into a large video store that it is almost impossible to tell its origins. Lake Cargelligo Civic has had its stalls and stage removed to form squash courts. Alterations have been done to the vestibule and former milk bar, but its facade is relatively intact. Lockhart Rio has seen its vestibule and projection suite altered, but its brightly-painted 1930s auditorium remains. The Criterion Hall at Narrandera was used as a Telstra depot for many years but in recent times has been used by the adjacent church which is the former Plaza Theatre. This bulding was converted into a church some years ago and, although parts of it are intact, it has lost its unity as a cinema. The Regent at Tamworth was converted into twin cinemas many years ago and retains parts of its 1930s decor. The downstairs section was converted into shops but it is planned to construct two small auditoria in this area in the short term. The facade of Temora's Strand remains but the interior was completely gutted in 1969. It is currently being used as a retail store. Above its street awning, Wagga Wagga Plaza retains its magnificent Spanish-esque facade. What was below the awning has been destroyed, as has the interior into which twin cinemas were built in the late 1980s. The Strand at Young has become a hardware shop but much of its cinematic detail has been retained.

There are three cinemas intact: the Saraton at Grafton; the Plaza at Laurieton; the Roxy at Leeton. While the first two are privately owned and operate as cinemas, the Roxy is owned by the local council and is available for film screenings, live shows, and other activities.

Six Extant Examples Worthy of Preservation

What has been demolished or extensively altered is beyond our capabilities to restore. However, there are a few extant examples which should be considered as buildings worthy of acknowledgment as memorials to Greek-Australian exhibitors and which can serve as landmarks for the descendants of those Hellenes. They are the Strand at Young (1923), the Saraton at Grafton (1926), the Roxy at Leeton (1930), the Rex at Corowa (1936), the Roxy at Bingara (1936), and the Plaza at Laurieton (1959).

Using material from the time when the theatres were opened and from available photographs, it is possible to describe in writing these six buildings. Much of the descriptions for the six theatres have been written in the present tense and contemporary quotations are used wherever possible to enhance the information presented.

Each theatre is different from the others, especially those built in the 1930s when the Modern style was in vogue. The Strand at Young and the Roxy at Leeton represent the fourth stage of theatre construction; the Saraton represents a mixture of stages four and five; the last three represent the fifth stage, the Plaza being an example of post-war Modern.

1. Strand Theatre, Young.

The Strand Theatre, at the corner of Boorowa and Clarke Streets, opened on Monday, 30 April 1923, the opening being performed by the local mayor "in the presence of a very large audience". The mayor noted in his speech that the building "was a great asset as well as an ornament to the town, credible alike to the architect and the builder." The newspaper reporting the opening spoke positively about the new building, mentioning the "elaborate furnishings, the beautiful white fibrolite ceiling, the comfortable seats, the orchestra, the lighting, and the general up-to-dateness of the theatre", claiming that it was a "complete and pleasurable surprise to all who had not previously seen the interior." Kouvelis wanted the local people to look upon the building not being privately owned but "built for them to take their amusements therein...".

The open-air smoker's balcony in front of the building upstairs is another splendid example of the careful planning and thoughtfulness of the proprietor, which will be fully appreciated by patrons on summer nights.

Beneath the street awning, the facade is divided into four sections, with a decoratively tiled pilaster between each. The main entrance doors are set on either side of the middle pilaster. The end sections are used for display boards and have small, horizontal windows above. These provide natural lighting for the two sets of dress circle stairways. Above the street awning, and stretching the width of the main entrance doorways, is the smokers' balcony. Access to this is afforded by a set of doors at either end, direct from the dress circle. Between these are two small square windows that designate the projection box. At each end of the facade are two large windows that can be opened at night for ventilation purposes. The facade returns into Clarke Street. Each window and doorway is decorated with a border of decorative tiles. Just below the top of the facade is a cornice with dentils, in the middle of which is a section suggesting a false roof overhang to form eaves. The middle section at the top of the facade is stepped and a decorative tile pattern highlights this stepped effect. Except for the tiled sections, the facade has been cement rendered and painted white.

The new theatre, both outwardly and inwardly , is a magnificent example of modern architecture..., is most harmoniously designed, the beautiful plaster and cement mouldings, and the exquisitely decorated ceilings, instantly attract the eye of the visitor...The approach from the street to the theatre is through a beautifully designed and decorated vestibule with approaches to the dress circle on either side.

The vestibule floor is patterned with small tiles, using two colours. A pentagonal-shaped ticket box, with tiled dado, is fixed to the wall between two double sets of doors with panelled skylights leading into the auditorium. The vestibule walls are texture-finished and the ceiling contains three shallow domes from which hanging pendant light fittings are suspended.

The auditorium is 50 feet wide by 100 feet deep, seated with chairs of the most comfortable and latest design...Off the gallery is a balcony, which will be a great convenience on hot nights...The tableau curtain, window and curtain decoration was specially designed and executed by Farmer and Co. Ltd. The fibro plaster proscenium and ceiling decoration were specially designed and modelled by Messrs. Weine and Co., Ltd., of Sydney. The electric lighting of the theatre has received special care, and the latest electrical appliances have been installed, the lighting generally throughout being indirect, with specially selected fittings. A special feature of the lighting is the dimming arrangement fitted to the house lighting...

The proscenium features a highly-decorated Ionic pilaster on either side surmounted by a decorated pediment, in the centre of which is a feature. The walls, while plain, have six large windows spaced along them on either side, each covered with pelmet and curtains. Colouring of the walls is in three sections, becoming lighter towards the top: the dado, from dado to above the windows, then to the ceiling. The hanging pendant light fittings are centrally located along the length of the ceiling.

The ceiling follows the form of a modified truss which has no bottom cord with two side panels following the pitch of the roof and a centre panel being horizontal beneath an intermediate tie-cord - the absence of a bottom rod being supplanted by tie-rods that are exposed below the ceiling connecting the centre of the truss to the springing-point at the walls. The sloping and central sections are of fibrous plaster panels fixed with battens. Across the width of each of the central sections is a ventilation grille, the centre of which features a diamond-shaped ceiling rose from which hangs a light fitting...

The theatre is equipped with a large stage, although this section has been constructed of corrugated iron, unlike the bulk of the building which is constructed of brick.

Special provision has been made for the orchestra, also dressing rooms for the stage for the convenience of artists. The picture screen has been specially constructed so that it can be moved back when the stage is used for concerts. The scenery, drop scene, and stage setting has been specially designed and painted by Messrs Clint Bros., of Sydney...The stage is specially illuminated with spot lights.

Designed by Soden and Glancy of Sydney, the theatre is "a monument to the artistic taste of the designers". For a municipality the size of Young (3,283 in 1921), the 1,000-seat Strand is an impressive investment. As the newspaper reporter covering the opening states,

Mr. Kouvelis could have pocketed these profits [ie from the open air and old Lyceum Hall] and gave[sic] the public less for their money...The proprietor has chosen however, to build a better theatre than exists in any country town or suburb in New South Wales, and whilst congratulating him upon his enterprise, we hope...that he will receive a good return for his outlay.

2. Saraton Theatre, Grafton.

Notaras Bros (John and Anthony) of Grafton entered the picture show business when they built the Saraton Theatre in Prince Street in 1926. According to the Government Architect's Report of 24 September 1925, the interior was to be 106 feet long by 53 feet wide, brick and concrete walls, steel and iron roof, wooden floor, with no stage or dressing rooms. Seating was for 1,100 downstairs and 494 in a gallery. The theatre was officially opened on 17 July 1926 by the Mayor of Grafton, Ald W T Robinson.

The Saraton, with its three shops in front...[has] a spacious vestibule, at the far end of which are two wide doors giving access to the stalls. Downstairs, the floor space is 106ft. by 53ft. and seating accommodation has been provided for 720 persons. The main auditorium, however, is capable of seating 1100 people, but the management have left vacant a space, which could be utilised for dancing, and in which it is possible to place an additional 300 seats.

The cinema is an important part of the streetscape, with the cinema entrance and shops (one on one side, two on the other of the cinema entry) presenting a unified whole.

Above the awning there are two twelve pane multipane windows to each shop. They are set in an orange-red brick wall with flat arches above each containing a stepped Art Deco keystone design. The auditorium, set back about ten metres from the street rises above the entry roof to display a wall with central pediment, beneath which is a projecting hipped roofed bio box. At each side of the central section there is a horizontal entablature and cornice, below which are arches outlined in the wall surface.

The auditorium is unceiled and audience members are able to see the underside of the galvanised iron roof. Walls are rough-rendered, with piers spaced along them, each decorated with an applied plaster capital. A window (for ventilation) is situated between each set of piers. Light pendants hang in two rows from the steel roof girders while, at stalls level, small spherical wall lights provide illumination. (By 1928 a stage and two dressing rooms had been built.)

From the centre of the entrance vestibule, access is provided to wide reinforced concrete stairs, leading to an intermediate floor or foyer, 53ft. by 12ft., thence to the large gallery, in which are 429 comfortable seats. The building is in every sense up to date, and is an acquisition to the town. Electric light, together with the latest fittings, has been installed throughout, and the work generally is a great credit to Mr. F.J. Board, the architect, and to Mr. Walters, the contractor, and all who have co-operated in its construction.

While Notaras Bros owned the building, they ran it for only a short time before leasing it to T J Dorgan who was developing a large circuit of cinemas in the far North Coast. It was not until the 1930s that the Saraton acquired its Art Deco interior which is currently intact.

3. Roxy Theatre, Leeton.

The 1,091-seat Roxy Theatre at 114 Pine Avenue, Leeton was built for George Conson to the designs of architects Kaberry and Chard. Supervising architect was G W A Welch of Leeton and W H Jones was the contractor (also of Leeton). Its opening night on Monday, 7 April 1930 was a huge success. The Roxy is a brick building, 120 feet long by 70 feet wide, and is situated on the corner of Pine Avenue and Chelmsford Place, thus affording it a prominent position in the town. When erected, the theatre was incomplete, and the Chief Secretary gave permission for a temporary stage (18 feet deep by 45 feet wide) to be installed until such time as Conson could finish the building.

Leeton may well be proud of its Roxy Theatre, which will stand out as a monument to the enterprise of Mr. George Conson, whose faith in the area and the future of the picture industry is expressed in a building which altogether will cost in the vicinity of £15,000..

Externally, the theatre is in a modified Spanish style with Art Deco elements, although neither style has been continued into the auditorium. The rendered facade is divided into three sections, with a slightly overhanging projection box jutting out from the top of the middle section. This has been made a feature of the building. Situated in a decorative frame below is the name of the theatre in cement letters. The side sections of the facade are decorated with pilasters, cornices, and other embellishments. It is the latter and the cornices that show a Spanish influence, while the remainder of the decoration suggests angular Art Deco. Below the street awning, the cinema entrance is centrally placed, with a shop on either side. Adorning the roof line are three neon signs, each spelling out 'ROXY'. One faces Chelmsford Place while the other two are fixed to the facade return walls and face Pine and Kurrajong Avenues respectively.

A feature of the Roxy is the vestibule, with its maple panels, and marble light standards on each side of the staircase. In the centre of the vestibule is a magnificent glass chandelier, while around the edge of the ceiling are concealed colored[sic] flood lights.

The architects used the Classical style on the proscenium, splays and balcony front, and appropriate decorative pieces were fixed to the rendered walls. The ceiling is a mixture of panels with strip covers and lattice squares for ventilation. No attempt has been made to cover or disguise the tie rods. Two rows of hanging pendant lights are fixed along the sides of the ceiling.

The ceiling of the main theatre is painted to tone with the general scheme...The stage drop curtain is blue and gold and is automatically controlled...The window curtains are of blue and cream and gold. The main interior of the theatre is lit up with thirteen 150 candle power lights, while there is also an auxiliary lighting service...

It was not until 1933 that the orchestra pit, proscenium and stage were installed. The proscenium has decorative moulding around it, painted in a mixture of red, yellow, blue and green. The main curtains and fringed valance are of dark blue, with gold appliqued swags near the bottom of the main tabs. 'RT' is appliqued to both curtains. Typical of the 1920s' Kaberry and Chard cinemas, the Roxy has two loges on either side which lead to exits from the dress circle. The curved splay walls do not reach the ceiling: they end about a metre or so from the top of the proscenium which is, itself, at least a metre from the ceiling line. They are decorated with pairs of pilasters on either end and three decorative frames spaced between. The ones on either side of the central, short one reach from dado to pediment and are in-filled with plaster decoration. The central frames are situated above exit doorways and have urn-shaped light fittings placed in the centre of each frame. The basic wall colour is light cream with old gold highlighting on the decorative plasterwork.

Change is inevitable and

The old Globe Theatre has outgrown its usefulness as a picture theatre. The Roxy, with its up-to-date magnificence and its spaciousness, will cater for a new era.

4. Roxy Theatre, Bingara,

In Maitland Street, Bingara, near the corner of Cunningham Street, stands the 480-seat Art Deco -style Roxy. It was not built without difficulties and it was never the success its originators hoped. George Psaltis, Emanuel Aroney and Peter Feros

...purchased a block of buildings in Maitland Street, Bingara, consisting of premises occupied by them as Refreshment rooms, and three other shops adjoining.

It is the firms[sic] intention of demolishing the existing buildings, and to replace them by modern and up to date premises. The work of demolishing that part of the buildings occupied by them as refreshment rooms is now in hand, and the building of modern premises will be proceeded with, the rebuilding of the shops will follow later.

Mr Psaltis informed me that he intends to erect a modern and up to date Picture Theatre...

The development was announced in June 1934 in the local Bingara newspaper. Plans for the shops and theatre received favourable comment. "When completed it will have an equal frontage to both streets, a symmetrical and well-balanced building, a splendid addition to the town's business houses." The architect for the cinema was W V E Woodforde of Sydney and construction of the cinema commenced in early 1935. It was subject to a number of alterations (believed to have been instigated by Psaltis) that resulted in extra time and expense. One of the alterations was to heighten the auditorium walls by 4 feet 6 inches to allow for the possible later inclusion of a dress circle. This brought about changes in decorative treatments of the main ceiling and proscenium.

It was not until the following year that the theatre opened.

Probably no event in the history of Bingara has caused more interest and excitement than the opening of the new Roxy Theatre, which took place on Saturday night last. The crowds which stormed the streets in the vicinity of the theatre...and long before the opening time, it was impossible to wend one's way through the crowd in front of the main entrance.

While its exterior is a basic rectangular interpretation of the Art Deco style, with pilasters and entablature and simple panelling to break up its cement-rendered wall surface, the interior is something different. Entry to the auditorium is through a long, narrow vestibule, the ticket box being situated in the middle at street entry (typical of USA cinemas). A short flight of steps leads up to the auditorium entry doors. The rear section of the auditorium is stepped and seating is fixed, whereas the front section is flat (for dances) and seating is moveable.

The auditorium decoration repeats the stepped motif of the facade, the ceiling stepping down to meet the walls at an entablature seemingly supported by pilasters. A wavy Art Deco frieze on the entablature and the perforated panels between the pilasters contrast with the angular theme. The wall panels comprise two elements, a central vertical row of five perforated, fan-like elements on each side of which are a vertical row of six rectangles containing diagonal strapping. The light fittings on the pilasters and proscenium splays are designed as angular vase elements. For Bingara, the Roxy is truly the "Theatre Moderne" (its advertised sub-title).

Reporting the opening performance on Saturday, 28 March 1936, the local newspaper said,

Great admiration was expressed at the beauty of the interior features of the theatre, and the wonderful coloured atmospheric lighting is certainly an innovation to Bingara. Changing from a soft white light to the effect of a rosy sunrise, the theatre gradually faded into soft blue lighting and the show was on.

And, the local mayor

...congratulated the management on their enterprise, saying that the theatre was a monument to the town and one of the finest buildings of its kind outside the city...Mr George Psaltis...received a flattering reception. He said it was the proudest moment of his life...He expressed...his appreciation of the support of the people of Bingara and district, whose friendship and encouragement had given them the inspiration to carry on in the face of all the obstacles that had beset them. They were but the servants of the people and they were out to give them the utmost value for their money, both in entertainment and service.

5. Rex Theatre, Corowa.

In 1935, when Nicholas Laurantus decided to erect a theatre at 190 Sangar Street, Corowa, he turned again to the architectural firm of Allan and Rowlands, Narrandera. They designed for him a 776-seat venue, with stepped gallery at the rear of the flat-floored stalls. The Rex, as it was called, opened on Saturday, 5 September 1936.

"The new picture hall in Corowa, called The Rex, was opened Saturday night last. There was a fairly representative attendance."

The Rex is slightly different to previous Laurantus theatres in that the vestibule is situated on the left of the theatre building in a semi-detached, single sto