Parthenons Down Under - Chapter 5 [Part B] of KEVIN CORK's Ph.D Thesis.

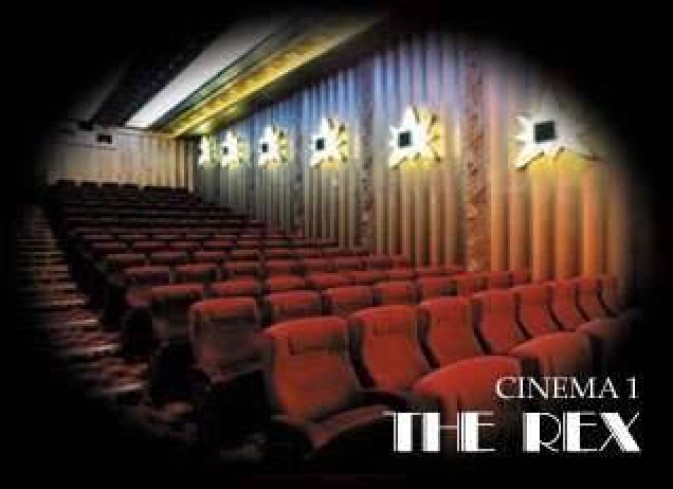

Rex Theatre, Corowa, NSW.

During the 1990's KEVIN CORK undertook extensive research into cinema's in Australia.

Tragically, he died before completing his work, but most of the chapters of his Ph.D Thesis, were completed.

His wife and children have kindly given permission for his work to be reproduced.

Most Australian's would be unaware of the degree to which Greeks, and particularly Kytherian Greeks dominated cinema ownership in Australia - especially in New South Wales.

Chapter 1 of Kevin's thesis makes the importance of the Hellenic and Kytherian contribution very clear.

It is difficult to know how to pass on to Kytherians the results of Kevin Cork's important research's.

In the end, I felt that the results should be passed on in the most extensive way - i.e. in full re-publication of Chapter's.

Eventually all Chapters will appear on the kythera-family web-site.

Other entries can be sourced by searching under "Cork" on the internal search engine.

See also, Kevin Cork, under People, subsection, High Achievers.

Continued from Part A, Chapter 5: Parthenons Down Under.

Plaza Theatre, Laurieton, (cont'd)

The theatre opened on Wednesday, 25 February 1959.

The theatre site is 110 feet to Laurie Street and 135 feet to Bold Street, with a small piece of the corner dedicated to a war memorial. Entry to the vestibule is at the corner, the vestibule running parallel to Laurie Street. The auditorium is built beside the vestibule but is longer. The facade and return wall are of brick; the remainder of the building is timber and asbestos cement sheeting. A two storey brick tower holding the vertical neon sign links the vestibule and auditorium.

The foyer-lounge is truly a delight in comfort. A ticket office is on the right whilst the massive windows and drapes, the somewhat artistic round pillar and recessed wall mirror are resplendent in the luxurious atmosphere.

Patrons enter from the right side of the foyer and the lounge-circle is right again, left of the stalls. Floors are stadious[sic] type, i.e. sloping from rear to stage, seating being erected in semi-circular fashion.

Internally, there is cement render to dado height and fibrous plaster above. The ceilings are of fibrous plaster and internal decoration is limited. Indirect wall lighting is used to soften the lines of the interior.

The interior colouring comprises two-tone grey ceiling...attractively latticed for air circulation, whilst top walls of frieze are lilac with a coral-rose dado. Lower half of walls are in silver grey and the wings are pale blue. The curtain is of red velvet and the seating is red and gold.

Seating is for 476. Facing Bold Street, and situated underneath the projection suite, is the confectionery shop.

'Whether Hatsatouris Bros. live or die, the Plaza will go on living - in Laurieton!' he [Peter Hatsatouris] declared. 'It will ever by YOURS - a monument to the confidence we have in your town, and will remain to be praised by succeeding generations for its boost to the entertainment of Laurieton.'

Mr. Hatsatouris said the theatre was a true local effort . . . built by local craftsmen . . . made mostly of local materials . . . and operated by local staff...'It is yours to enjoy...'

Preserving Our Ethnic Past - Fulfilling the Guidelines

In the Introduction to the Movie Theatre Heritage Register for New South Wales 1896 - 1996, the writers state that

Almost no purpose-built cinemas have been recognised in New South Wales (or indeed the whole of Australia) as items of environmental heritage by their having Permanent Conservation Orders (PCO) placed upon them. In fact there are almost none. Compared to the building genre of domestic architecture, their representation is less than minuscule.

Compared to other types of buildings (for example churches and houses), cinemas and theatres have not been acknowledged as important pieces of our state's heritage. The Introduction discusses why some types of buildings are considered environmental heritage items more than others by reviewing the Reports of Commissions of Inquiry into four cinemas upon which PCOs were sought. One of the difficulties with the inquiries was that there are many who perceive heritage to be "associated with age or antiquity and/or items associated with high culture." At the time of the Wintergarden Theatre, Rose Bay Inquiry in 1985, there was only one cinema (ie the State Theatre, Sydney) on the register of the National Estate, but it was also noted that on it were 40 Gothic Revival churches in the Sydney Region. Sadly, the Wintergarden was not considered to be of equal heritage worth and subsequently demolished. The Commissioner of Inquiry stated,

For these arguments to be valid the phenomena of public entertainment would need to be of the same cultural significance as religion. Though both phenomena have deep roots in our past, I doubt if they could be held to be comparable in any way.

He went on to say,

Anyone who experienced the phenomenon of going to the movies before the advent of television would now be in their early 40s at least. In 50 years time there will be practically no-one alive who will have experienced it. Of what interest to that generation will be the movie experience of the 1920s-1950s' generation.

In the light of this statement, one might ask similar questions about the heritage value of former royal palaces, ancient Greek temples, old steam ferries, cemeteries, Aboriginal sacred places, and Christian churches (especially if one is of a non-Christian faith). As Thorne's Introduction points out, the tradition of mass entertainment has its roots in ancient Greece and, whereas pagan temples and Christian churches "represent segments in the history of the social and psychological need for many or most human beings", cinemas are also a representative segment of mass entertainment. This has long been ignored and should be redressed.

In 1979 the Australian ICOMOS Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Significance (aka Burra Charter) was adopted as the standard for heritage conservation practice in Australia. The charter set down guidelines that "apply to any place likely to be of cultural significance regardless of its type or size." Not the word "type". Cultural significance "means 'aesthetic, historic, scientific or social value for past, present or future generations'." The cinemas listed above do have considerable cultural significance (aesthetic, historic, scientific and social value) not only in terms of their local area but in relation to this state. In addition to this, they have national significance since they are part of our Greek migrant heritage. Briefly, their architectural and decorative schemes reflect the periods in which they were constructed. Being the type of building that they are, architects and exhibitors utilised the latest ideas in their design and construction. Aesthetically they were pleasing to the people of those times and give future generations first hand knowledge of period design and decoration of a particular genre of building. Although the buildings listed are not known to have been the scenes of momentous, historic events, they are part of the history of mass entertainment. The invention and development of moving pictures and their exhibition is a specific event in the history of popular entertainment (which started in ancient Greece). As well, the films exhibited at the cinemas starred many notable exponents of the acting profession (including people such as Laurence Olivier, Judith Anderson) and many were directed by foremost cinematic directors (for example Alfred Hitchcock and Cecil B DeMille). If it were not for the medium of film, most Australians would never have been able to experience the work of these people. When the cinemas listed above were built, they utilised the latest in scientific technology for film projection, electric lighting (including neon) as part of the decor, and other mechanical devices (such as automatic ticket machines, electric fans and motors). The social aspect of going to the pictures has already been discussed in a previous chapter and does not need to be reiterated. The cinemas listed had relevance for past generations, and have relevance for present and future generations.

Heritage Studies is a guideline for ascertaining the significance of a place using a three-step management system described in the NSW Heritage Manual, viz investigate significance, assess significance and manage significance. To determine the importance of a site, a list of 35 historical themes relevant to this state is provided in the Manual itself. Added to this are 9 "Draft National Historical Themes" compiled by the Australian Heritage Commission. Even a cursory glance at both lists reveals that the 6 cinemas listed above fit into a number of themes. In the national ones, they relate to: No 2 Peopling the continent; No 3 Developing local, regional and national economies; No 4 Building settlements, towns and cities; No 5 Working; No 6 Educating; No 8 Developing cultural institutions and ways of life; No 9 Marking the phases of life. From the state list, the cinemas fit the following themes: No 1 Aboriginal contact; No 10 Townships; No 11 Migration; No 12 Ethnic influences; No 14 Communication; No 18 Commerce; No 19 Technology; No 25 Social institutions; No 26 Cultural sites ("from low to high culture"); No 27 Leisure; No 32 Education; No 35 Persons.

Taking the national themes, the 6 cinemas are directly linked to the 10 Greek men who were responsible for them and they represent the much larger group of immigrants (theme No 2) who came to this country from Greece. Because of their lack of English and other skills, they were forced to seek employment wherever they could obtain it. This meant that, often, they had to move to country towns. In these places, their work as food providers and cinema exhibitors should not be under-estimated. Through their hard work and perseverance, they helped the economies of the towns in which they lived (theme No 3). The building and operation of their cinemas created employment for local people (theme No 4), thereby adding to the local economy and helping to foster further growth within the towns (refer to comments by Mayors at beginning of this chapter). The exhibitors all started in the food trade and moved into cinema exhibition, thereby showing that this country was not inflexible in its acceptance of one endeavouring to better oneself. Their working lives (theme No 5) deserve to be acknowledged. The cinemas themselves provided education for the masses who attended, offering them glimpses of faraway places, famous actors, stories both incredible and mundane, news, travelogues, etc. The influence of the cinema affected our cultural outlook in numerous aspects of daily life - in fashion, architecture, decoration, music, literature, to name a few (theme No 8). With the rise of cinema and its subsequent decline in favour of television - from being part of a large group and experiencing social interaction to the predominantly anti-social television viewing of the post 1960s - the six cinemas represent the passing of a phase of life. The Strand at Young (1923) represents an early example, while the Plaza at Laurieton (1959) shows the end of an era in its design, construction and decoration.

At a state level, the 6 cinemas fit into 12 of the historical themes listed. The overall treatment of Aborigines (theme No 1) in the first half of this century is reflected in the way they were treated at country cinemas - a separate seating section and often having to use a separate doorway. While this was not "interaction", as stated in the list of themes, it was discrimination expected at the time and the cinema exhibitors were forced to follow community expectations. One might refer to it as reverse interaction.

Theme No 10 "Townships" includes the growth and development of towns. The Greek refreshment rooms and the Greek-owned cinemas added to each town's growth and development. While Greek food might not have been served in their refreshment rooms, "Aussie-fare" was fed to countless thousands. The cinemas were social gathering places that provided entertainment for many years and were important edifices in their streetscapes. "...a credit to the town and district" said the Leeton Mayor in 1930." "...a monument to the town and one of the finest buildings of its kind outside the city..." said the Mayor of Bingara in 1936. (In the case of Bingara, the adjoining shops and residence must be considered along with the theatre.) If these buildings were acknowledged worthy of such comments when they were built, are they not worthy today?

Theme No 11 is "Migration" and the 6 cinemas may be taken as the culmination of the lives of the men who came from Greece so long ago. Having worked as shop assistants, taught themselves English, operated refreshment rooms, they moved slowly up the ladder of success to become theatre managers, prominent men in their towns. The cinemas buildings represent that ascent: the seeking and achievement of success. The next theme (No 12 "Ethnic influences") is tied to the earlier one. These same men (those who married and had families), were determined that their own children should not have to go through the hardships that they had experienced. They worked hard, became financially successful, saw to it that their children were well educated at secondary and, quite often, tertiary levels, with many entering the legal, medical and accounting professions. This work ethic, engendered into the young men who arrived from Greece so long ago, has influenced others who have seen them become successful. While this may not always have been free from envy and racist taunts, it has proved that Australia is a land of opportunity and people can rise to "comfortable" heights.

"Communication" (theme No 14) is synonymous with mass media, and the cinema, in its heyday from c1910 to the early 1960s (in country NSW), was THE mass medium. Theme 32 "Education" is linked to this theme. People learnt about the world from the films that they saw. Places where they could only hope to travel, people and cultures about which they might only have read. Great actors of the English-speaking stage brought Shakespeare to country towns through the films in which they starred. Musicals with both popular music and the classics filled the ears of those present in the auditoria. People could hear Mario Lanza in "The Student Prince" (released 1954), see Leopold Stokowski conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra in "Fantasia" (released 1940), or watch big names from the swing bands in any number of films made in the 1930s and 1940s. People watched to see the latest fashions, furnishings, types of cars, architecture, accessories, etc. It was not unusual for newspapers (especially in the 1930s) to have sections for ladies on where film starlets lived, or what they were wearing or using on their faces.

Cinemas contributed to the retail establishments of the towns, whether through food purchases or purchases associated with what people had seen on the screens. They provided jobs for people (ushers, projectionists, cleaners, lolly boys, cashiers, odd-jobbers) which, in turn, assisted the commercial life of a town. (Theme No 18 "Commerce") A number of the exhibitors did not only operate cinemas. As shown in Chapter 8, there were quite a few who became involved with other commercial enterprises which helped the towns to grow (eg electricity supply, ice works).

For the cinemas to work correctly, they needed to have the appropriate "Technology" (Theme No 19). Building construction techniques improved as the years past. From the early days, cinemas had to be equipped with the latest in projection equipment and, with the coming of sound, had to be updated or replaced. Better interior and exterior lighting was employed by exhibitors as they sought to improve their buildings, thereby adding value to their properties and prestige to the towns themselves. Even adding an electric motor to a stage curtain or installing "deaf aids" were technological advances. As wide screen formats arrived in the early 1950s, new technology was used to offer patrons CinemaScope films and better sound systems. In order to maintain film supply and patronage, exhibitors were forced to keep abreast of the latest technology.

Theme No 25 "Social institutions" offers examples where people might come together to experience social interaction (eg CWA, Masonic lodges). In its day, the cinema was probably more of a place for social interaction than any other institution, including churches. As well, it was egalitarian (except for Aborigines as mentioned above). The following table shows the popularity of cinemas over other forms of social interaction in 1921. While church attendance and social clubs were not subject to any entertainment tax, it is probable that they did not have anywhere near the level of attendance of those entertainments listed below.

Entertainment

City (Sydney)

Suburbs (Sydney)

Country NSW

Racing

---

2,455,720

820,092

Theatricals

2,714,962

1,031,729

799,111

Picture Shows

7,822,110

11,571,082

8,785,739

Dancing & Skating

253,446

703,664

537,980

Concerts

146,485

54,486

151,227

Miscellaneous

768,209

1,338,422

1,506,699

Taxable admissions totalled 28,178,931 and the population of NSW according to the 1921 Census was 2,099,763. A simple calculation reveals that everyone in the state attended the pictures 13.4 times during 1921. The figure would be higher if one were to include non-taxable admissions and eliminate the very young, the old and infirm and those not interested in attending.

The cinema venues were important "Cultural sites" (Theme No 26). They may be taken by some to represent "low" culture, but the figures above and those offered in the Appendices indicate that the cinema was an important part of our cultural life as we watched Australian-made films, or stayed in touch with our roots via English films or learnt new ways from American films. The next theme (No 27 "Leisure") is closely linked to No 26. The taxable admissions speak for themselves. Australians have enjoyed leisurely pursuits and our working standards in the first half of the twentieth century guaranteed leisure times and the cinema was a major activity geared to meeting this. For example, Saturday afternoon at "the flicks" was an institution for millions of children.

Australians have been educated (some may argue for worse rather than better) by the films that we have seen. When one considers the number of cinema admissions per year from c1920 to the early 1950s (as listed in the appendices), there is every reason to believe that the number attending churches was a lot less. If some people learnt their moral values from churches, there is the strong probability that many more learnt them from secular and cultural education which included visiting the cinema, hence the importance placed on the Chief Censor. It was not until the second half of this century that cinema "baddies" started to win (often with an overuse of violence) and, as a result, our social values have been challenged. In "'the old days", morals were upheld, good was promoted and virtue rewarded in the films that we saw. Besides the many and varied feature films, patrons saw newsreels, travelogues, educational featurettes, musical interludes, cartoons. All of these provided (Theme No 32) "Education". In the mid-1920s, for example, patrons in some places had demonstration films on how to do the latest dances, while at Bogan Gate it was recorded that the Sunshine Harvester Company screened special films for farmers in 1929.

The final theme (No 35 "Persons") encompasses each and everyone of the Greek-Australian exhibitors and their life-stories. Theirs were not easy lives, but they showed that it was possible to triumph over adversities (whether lack of English and work skills, fires, economic hardships, discrimination, etc). The story of these Greek men, and the wives who helped them, is part of our nation's migration history and deserves recognition. These men went beyond the refreshment room stage - they became cinema exhibitors and entertained the masses.

From 1915 to the early 1960s, the Greek-Australian exhibitors provided a service for millions who passed through the doors of their cinemas. If one were to take, for example the Luxury Theatre at Walgett and attempt to approximate the number of people it served from the time of its opening in 1937 to 1962, the figures would show that over 950,000 patrons passed through its doors. This figure is a conservative estimate. This is based on two-thirds of the theatre's seating capacity and the number of screenings over 25 years. From 1937 to 1940, it screened three times each week, giving an estimated attendance of 155,844. For the next 22 years, it screened twice weekly, with a small number, say 5, extra public holiday or special function screenings. This would give a patronage of approximately 798,534. It is most probable that Saturday nights were full houses and the numbers given here are on the low-side. The figures do not include numbers who attended balls, dances and other functions on non-picture nights. If similar calculations were applied to the six cinemas listed above that are being suggested for heritage listing, then it could be shown that they have served millions of people during their cinematic lives.

Is It Too Late?

Besides the social, cultural and education functions of these buildings, one should not forget their architectural merits, each representing different aspects of cinema building development. While having been converted into a hardware store, the Strand at Young retains much of its original decoration. The stage has been sealed-off, but the proscenium remains. The original ceiling is extant, although modern florescent light fittings hang from it. At the rear of the dress circle, the projection box has had its portholes covered. The decorative dress circle balustrade survives. Along the side walls, the ventilation windows have been opened up and plain glass installed, to provide natural light. The facade has been painted an unbecoming dark brown, the effect of which is to lessen the height of the building and make the decorative features less discernible. However, the conversion has been sympathetic and, although it may not be economically practical to convert the building into a cinema or community centre (there is a large Town Hall in Young), the Strand should be protected from further alterations or demolition as it is a good example of a 1920s picture theatre and was the first major building project undertaken by Jack Kouvelis.

Although still a single screen cinema, the Saraton at Grafton (1926) leads a precarious life. Should a multiplex centre be built in the town, the days of the Saraton would surely be numbered. Seating over 1000 on two levels, the theatre is capable of being converted into a community centre, with the income from the shops in front helping to off-set its running costs. Internally, the building was modernised in the 1930s, turning it into a modest Art Deco cinema. Its wide stage, replete with orchestra pit in front, is suitable for small, live productions. The building is in good condition throughout, according to the owner when telephoned in 1996. While it is in constant use for films, it has no preservation order on it and could be lost in the event already stated of a multiplex being built. Similarly, it would be a great loss to the state's cinema heritage if it were to be twinned, tripled, or so forth, as the Saraton is a delightful representative of a 1920s facade and 1930s Moderne interior. "The theatre is one of the most decorative and architecturally handsome in NSW." While the Notaras brothers who built it, only operated it for a few years before leasing it to a northern rivers' circuit of cinemas until the late 1960s. Since its re-opening in 1982, the family has retained exhibitorship.

In Leeton, when the Roxy was threatened with redevelopment in 1977, the local community fund-raised approximately one-third of the purchase price and the local council contributed the rest. Ownership is vested in the local council and the theatre has been progressively upgraded to provide a larger stage area, new dressing rooms, and better live theatre facilities. It is used for live presentations and films. Fortunately, the National Trust has classified the theatre. Installed in the theatre in 1987 was a WurliTzer theatre organ, purchased by the Leeton and District Community Advancement Fund. "The interior of the theatre is also virtually intact from its date of construction, and offers a rare experience to view a country picture theatre...still serving its community some 65 years after opening." Its facade is memorable, but the quality of interior decoration, when compared with the Saraton at Grafton, the Roxy at Bingara and the Rex at Corowa, is of a lesser degree. Yet, if the Leeton theatre has been classified, then the other three should also be, because of their better architectural and decorative merits, and for their Greek connections.

At Bingara, the corner two storey block, with adjoining cinema and shop must be seen as one unit. The Roxy has been used primarily for storage purposes since its closure in 1959. The vestibule with its street-facing ticket box is extant, and a cafe operates in the vestibule. A small kitchen has been built into part of this area but, according to a local resident, the public can still enter the auditorium through the original doors "to have a look". The raked rear section is intact, complete with original seats. The flat stalls area is used for storage. Most of the auditorium decoration is intact, as is the original paintwork, although it has been neglected for many years. The theatre's proscenium was never altered to show CinemaScope. Hence, its original appearance has been preserved. The adjacent shops still function and, above the corner one, the residence is still in use. The town itself is without a community centre with theatrical capabilities and the Roxy could be utilised as such. If necessary, the adjacent two-storey shop and residence could provide extra foyer, administrative, dressing room and storage space. "As an almost-untouched Art Deco country cinema of the middle 1930s, it is a rare surviving example of its type and era." The corner block as a whole is worthy of acknowledgment for its Greek connection, while the cinema in particular is a sole survivor of a particular architectural genre.

Corowa's Rex theatre is in use as a retail store and retains most of its cinematic elements. Even the main stage curtains (installed in front of the proscenium in the 1950s for CinemaScope) remain, albeit swept upwards to keep them out of the way of customers. Behind these curtains, the original proscenium is intact. All of the vivid yellow and red Art Deco stencilled motifs remain on the walls, proscenium and ceiling. There is little possibility that it will ever be returned to its original use. However, provision should be made to ensure that its architecture and decoration are retained in the event of its present use being changed. It is an excellent example of decorating using stencils rather than plaster (as at Bingara) and its vibrancy is as alive today as it was when Nicholas Laurantus opened it in 1936. "Unlike the more subdued decoration of other Art Deco cinemas, the Rex's decor provides a touch of sparkle to what otherwise is a typical county town."

The final cinema is the Plaza at Laurieton (1959). Built in the post-war architectural doldrums, it nevertheless is representative of that style. Its connection with the Hatsatouris brothers who had a number of cinemas in the area, stretching back to the late 1920s, gives it an historical connection. The Plaza operates today (as a single screen). "While the Plaza could be described as typical of the cinema buildings once found in coastal holiday areas to trade off tourism, particularly in Queensland, according to G Hatsatouris, it was better than most." It is a good example of late 1950s architecture of which there are, unfortunately, very few surviving cinemas left with which to compare it.

We cannot always judge what should be preserved by simply demanding that only the prime examples be kept. If this were the case with church buildings, then only major cathedrals in capital cities would be retained. This idea is refuted by the fact that the National Trust list contains many churches. In the case of cinema buildings, much of what might have been considered to have been "the best" has already disappeared because, when they closed in the 1960s and 1970s, too few people were concerned about this "low" cultural form. The same arguments can be put forward regarding preservation of former Greek refreshment rooms. It is important that these not be judged solely against the Paragon at Katoomba.

Apathy or Ignorance?

A survey of the local councils in whose areas the six cinemas above are located has revealed the following. In Young, there is no listing of the former Strand. It is not even in the Council's Local Environment Plan (LEP). At Grafton, the Saraton is merely a part of the Grafton Urban Conservation Area plan. It is not listed separately in Council's LEP, although a council representative stated that any proposed development of the building would mean close scrutiny to ensure that what was planned fitted aesthetically into the general area. Nothing was said about the heritage value of the existing building. The Bingara Roxy (and shops) has no listing on it at all. In Corowa, the Rex is listed in the LEP. Hastings Shire Council has not listed the Plaza at Laurieton on its LEP. In Leeton, the Roxy is listed in the LEP and, as already stated, has a National Trust classification. Not one of the buildings has any permanent conservation order on it. It was suggested to the writer that such an order on the Leeton theatre would be unnecessary since it is council-owned. Even a "safe" situation as this could be endangered should the right set of circumstances arise. While this writer commends local councils who have placed theatre buildings (both current and former) on Local Environment Plans, it is not sufficient to ensure their preservation. Because they are such prominent buildings in their communities, full and proper heritage studies should be undertaken, especially if there is any hint of a proposed re-development. These buildings are important on, at least, a state-wide basis and they need to be noted on something more than a local council list.

Figures available from the 1991 Census (the latest available at the time of writing) show that in Australia 136,028 people claimed to have been born in Greece. A further 151,082 indicated that they were second generation Greek, of who 49,706 resided in New South Wales. The Census found that, in New South Wales, 44,330 people claimed to be of Greek origin. Those who indicated that Greek was spoken in their homes numbered 94,814. It would be reasonable to assume that there are many Australians living in this state who do not speak Greek in their homes although their forebears were Greek. Their number will continue to increase as time passes, but it will not necessarily mean any lessening of their Greek or Greek-Australian heritages. It should be that each state of the Commonwealth ensures that all nationalities represented in our population should have specifically designated landmarks relative to them. These should be preserved for posterity, seen not as divisive elements, but as agents for the promulgation of the diversity and rich cultural mix of our nation's population. There was a time when Chinese immigrants and their establishments were considered by many to be unfavourable and disreputable. One only has to visit the specific migrant-related landmark called Chinatown in Sydney to realise that it has developed a sense of place in the minds of, not only Australians with Chinese backgrounds, but Australians generally and overseas tourists. A similar situation occurs at Cabramatta with its strong Vietnamese influence. Unfortunately, the pre-World War II Greek migrants did not "congregate" within a specific area nor have "tribal lands" such as the Aborigines. They were forced, as has already been noted, to move to many different places throughout the state in order to seek work. It is not as simple as declaring a small area as a landmark to them. Their contribution, by necessity, must be landmarks (buildings and sites) scattered across the state to show future generations what these people achieved.

In early 1997, a small, one-question survey was undertaken by the writer to identify Greek landmarks in New South Wales. Its findings show ground for concern. Three groups of people were selected: children of Greek-born, former exhibitors (Group 1); grandchildren of Greek-born, former exhibitors (Group 2); young people whose families were not associated with cinema exhibition but who have either Greek-born parents or grandparents (Group 3). The question asked was "What do you consider to be Greek landmarks (ie artefact, building or site) in this state?" A total of ten people were surveyed. Although it was planned to survey twice that number, it was felt that, because each person experienced difficulties in answering the question, it would serve little purpose to pursue the matter any further. The results are as follows. Three people (one from Group 2 and two from Group 3) could not name any Greek landmarks. The other seven suggested several Greek Orthodox churches (Holy Trinity at Surry Hills received 7 responses), three people from Group 1 suggested the Paragon Cafe at Katoomba, one (from Group 2) thought that the Greek section at Botany Cemetery was noteworthy. Because the Kytheran Brotherhood was formed in 1922 at the former Marathon Cafe in Oxford Street, this building was thought by a Group 2 person to be of importance. Another suggested the suburb of Marrickville (but this area's Greek links are not as strong as they were two or three decades ago). One person (from Group 1) suggested the Kastellorizian Club in Kingsford. It should be kept in mind that churches and clubs are usually community-based ventures of particular, often ethnic, groups rather than the work of a particular person or family. Thus, the survey has shown that there is a noteworthy lack of Greek landmarks in this state to acknowledge the role of individuals or families.

Australian society abounds in Anglo-Saxon landmarks (secular and religious) and, in the past decade or so, has come to be more receptive towards Aboriginal landmarks. It is usual for landmarks to be protected by government legislation. What, then, of the minorities who have helped to populate this country? It is nearly 160 years since the first free Greek came to New South Wales, thereafter, and possibly unintentionally, setting up a chain of migration that became much more than a trickle after World War II. Yet, there are no recognisable landmarks for these people. The same claim can be made on behalf of most minority groups (eg Italians, Indians). If multiculturalism, whether we wish it or not, is to be embodied in our psyche, then landmarks for each nationality who migrated to these shores must be identified, acknowledged, protected and preserved so that future generations of Australians are given opportunities to appreciate the sacrifices made by earlier settlers and respect their achievements.

Our interest in heritage and history has become more finely honed since the Bi-centennial in 1988. For many, this milestone sent people seeking information about their forebears. If we are to acknowledge the part played by all migrants in the development of this state, then we need representative landmarks, ones that attempt to cover many facets of their lives rather than solely spiritual. For the Greeks, what better than the six sites suggested in this chapter. The cinemas were built for the towns in which they were situated and this required faith in those towns by their builders. The men from whose minds the germ of the idea for these buildings first sprang had arrived in this country at a young age, with no English, few skills, very little money, and often alone. In order to succeed they had to "go bush" in their younger years. Once there, they grasped the opportunities offered by their adopted nation and, through integration and hard work, proved that it was possible to succeed. Practical considerations, such as prevailing economic conditions and population potential, had to be taken into account when deciding upon designs for their cinemas, but each town where Greeks built and exhibited had its very own "Parthenon".

Writing about the Acropolis in Athens, R J Hopper stated that "The Parthenon...was the great monument of Athenian glory" and represented the pinnacle of Athenian architectural and artistic endeavours. The six cinemas above are the tangible embodiments of the dreams of the Greek-Australian exhibitors. They are monuments to their glory, regardless of the construction style in which they were built. The buildings were meeting places for innumerable people of various races and creeds, places of entertainment, aesthetically pleasing, technologically and architecturally advanced for their times, and were built for the betterment of their towns. It could be argued that finer examples have already, to use film jargon, "bitten the dust" and that these six are less than fine. Since there is only a limited number from which to choose for preservation purposes, it is necessary to seek from among those extant and these six are representative of their architectural and decorative styles and are linked to our state's Greek migrants. If they are permitted to follow the same path as the 16 already demolished (out of the 34 built for Greeks), or be further altered, then future generations will have nothing of worth with which to acknowledge the physical embodiment of the achievement of the 66 Greek men who provided cinematic and other entertainment in this state from 1915 to at least the early 1960s. The six theatres deserve proper protection so that future generations (of whatever descent) can appreciate them for what they are - landmarks of Greek-Australians, viz "Parthenons Down Under".