The big outdoors

BY: CATHERINE MARSHALL

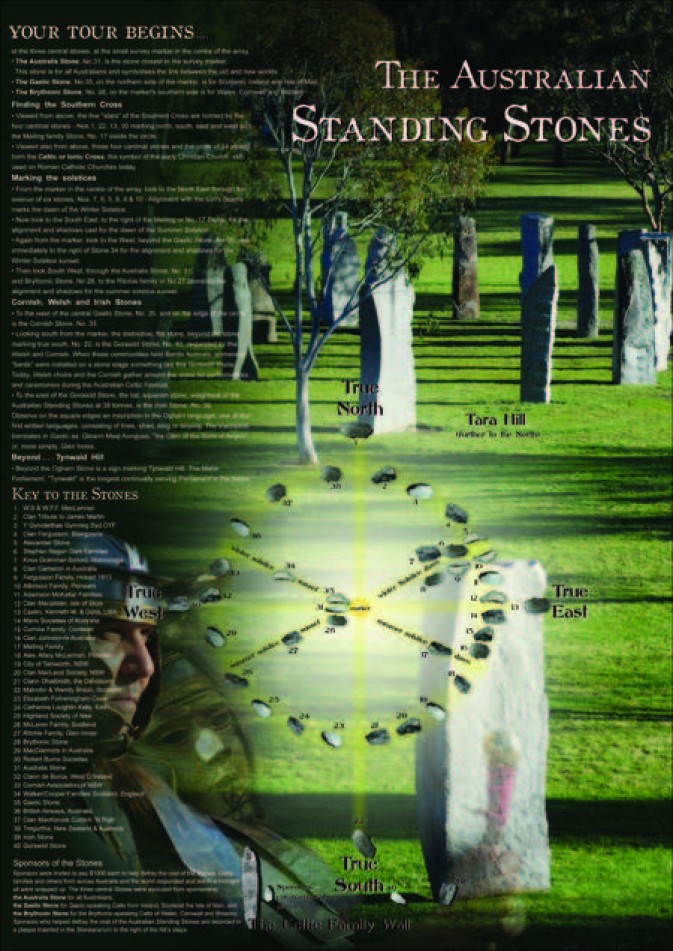

Photograph: The Australian Standing Stones at Glenn Innes.

Picture: http://www.gleninnestourism.com/pages/australian-standing-stones

This article is included as as good general overview for travelling around the North Western part of NSW by road. When Kytherians go to visit the Kytherian iconic and sacred site of the Roxy complex in Bingara, they will know that there are many more interesting sites to visit in the immediate area.

The rains are coming to Moree in the northwest New England region of NSW, driven westwards from the drowned plains of the NSW central west, and southwards from Queensland, where floods will soon swallow the land whole.

My visit is in mid-December and already the crops have been ruined. Stuart Boydell plucks a head of wheat and releases the grain with his thumb.

"Too much rain during the growing season," he laments. "It's almost halved the price." And there is more to come.

"They say if you see a carpet snake the rains are coming," says his daughter, Dimity. But there's nothing to fear tonight, for the warmth hangs cloak-like over the family's homestead, Cooma, and stars pierce the black sky. There is a pool in the garden but beyond it, past the gravel tennis court and the gazebo where guests sip champagne through candy-striped straws, is something far more enticing: a picture-book yabby pond from which our entree has just been scooped.

The deluge hasn't troubled these crustaceans, nor the pecans in the dessert. "When they were babies the trees had opera played to them," says Stuart of the nearby pecan farm, the largest in the southern hemisphere. "No one complained, because it worked."

Such quirky farming techniques and unpredictable weather patterns don't deter the tourists: they pour into Moree to avail themselves of expansive landscapes, fresh produce and hot artesian baths, said to ease ailments and deliver an analgesic stupor.

The drive south to Narrabri is pleasantly soporific, too, with one vast cotton field indistinguishable from the next until we reach Bellata, a village dwarfed by the biggest grain silo in this region. At Narrabri, the Namoi River has burst its banks so that it resembles a squat brown snake.

We sit on the steps of The Crossing Theatre and workshop with artist Nancy Hunt, one of six generations who've lived off this mercurial land. My watercolours can't replicate the jersey-print trunks of the river gums, so I lay down my brush and listen instead to Max Pringle, who recites bush poetry nearby. Then at lunch, yabbies make another appearance, alongside sweet, locally reared Inglegreen pork. Our tipple has been brought in from Wee Waa in the flooded Namoi Valley, where Lindy Widauer runs Seplin Estate Wines. "We came in on an aqua rider with two people, two dogs and all these bottles of wine," she says.

No obstacle is too great for the people who live in Big Sky Country, where a little rain goes a long way and too much won't dampen the spirit. Narrabri's museum reflects such resilience, and the quirks and oddities of this town.

"Electricity was meant to come here in 1911 but someone [started] a rumour that it interfered with women's metabolisms and made them funny," says Pringle the bush poet. "So they held a referendum and voted it down, and Narrabri only got electricity in the 1920s."

Northwest from here, we detour into Mount Kaputar National Park, swatting persistent mosquitoes as we go.

Our reward is an exhilarating view of Sawn Rocks, pentagonal basalt pipes that spring up from Bobbiwaa Creek. It's a startling formation, secreted away in the Nandewar Range.

Up the road is another revelation, the town of Bingara, where Greek immigrants opened a milk bar named The Roxy in the 30s.

The Gwydir Shire Council is restoring this art deco building with its melamine counters and flashy neon signs. "It epitomises the story of Greek immigration to northern NSW," says Sandy McNaughton, a Melburnian who fell for a local farmer and now manages The Roxy.

We have moved on from the flat western plains to the green curves of New England. At Olives of Beaulieu, 15 varieties of the fruit thrive alongside cherry, pear and walnut trees, an earthy and sophisticated bounty of robust fruit, infused oils and spice blends inspired by North Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

Just outside Inverell, Blair

Athol Estate, a seven-guestroom historic manor house, sits surrounded by English and kauri pines, Moreton Bay figs and rotund bottle trees. The original owners are buried in the garden, but ghost sightings aren't mentioned when we gather around the breakfast table.

Also buried in these hills are curiosities of another kind: sapphires so plentiful as to earn Inverell the dazzling moniker of Sapphire City. Bill Dawson has mined the gems for 40 years, and still works his claim seven days a week. "It's heaven," he says, holding a sapphire to the sun, turning it until the light flares within, illuminating each feather and veil. "Every day is a surprise; you don't know what you're going to find."

Dark clouds follow us eastwards to Glen Innes where they encircle the Australian Standing Stones. A healer walks her dog here; she says she moved to Glen Innes for the stones. "They have an energy about them. At certain times of the year the dowsing rods show us where that energy is."

But rain threatens to wash away the positive vibes, for the ground is sodden and the farmers are suffering. Farmers can't get stock to the market because it's too wet, says butcher Bluey Campbell.

Steak remains a popular choice nonetheless on the menus around town: at Restaurant Ninety8, in the historic New England Club and at Hereford Steakhouse, where guests who conquer The Beast, a 1kg cut, are commemorated on a roll of honour. I receive a mention for consuming two decadent chocolate pithiviers.

The steak and chocolate and local pinot gris are easily slept off at the stately Tudor House B & B, where the beds are cavernous and the linen crisp and soothing. We are headed next morning for Armidale, with its cathedral-spiked skyline.

The New England Regional Art Museum is unusually accessible, with its treasure-filled vault from which locals were allowed to curate their own exhibition, and its wide corridor where someone casually paints a self-portrait.

Next door, at the Aboriginal Cultural Centre and Keeping Place, bush tucker has been set out for morning tea: dollops of lilli pilli and rosella jam sliding off hot scones, wild lime muffins and garlic damper set out on palm leaves, fragrant mugs of lemon myrtle tea. I pour a cup for Steve Widders, a blind Aboriginal painter who is exhibiting for the first time.

"I can't read and I can't do photography, but I can use my hands," Widders says. "I have someone with me when I paint. I say I want an orange-pink or a dark blood-red. It's all about my perception of colour, even though I'm blind."

Perception, yes: an essential ingredient for anyone who lives out here in the bush, where nature wields such unfathomable power. By the time we reach Peterson's Winery and Guesthouse, the rain has fled, leaving behind emerald fields and sun-spangled air. Peterson's manager, Sandy Harris, gazes out contentedly.

"On a day like today, you could practically watch the vines grow," he says.

Catherine Marshall was a guest of New England North West Tourism.