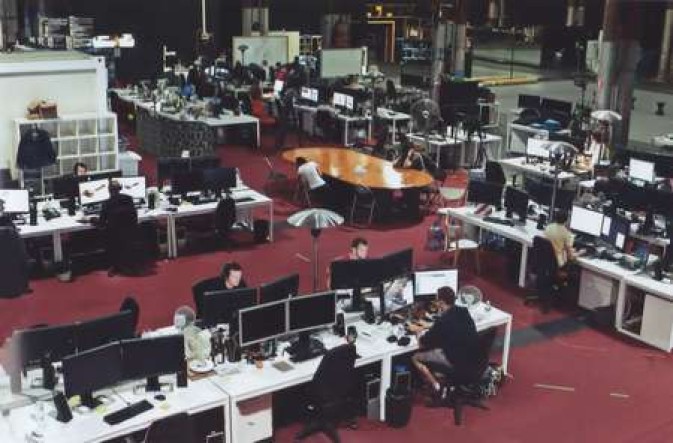

Massive production studio at CarriageWorks, Redfern Sydney

where George Miller's Happy Feet 2 was produced.

You see the animation team that numbered 670 at its peak, working on production and sound editing.

Australian Financial Review.

December EDITION, 2011

pp. 1, & 28-34

Brook Turner

Photograph: Dr D studios at Sydney’s CarriageWorks, Redfern, Sydney. Photo by Nic Walker

Millers Crossing

Four years after reaching the pinnacle of his pfofession, George Miller has embarked on a whole new game.

As Brook Turner writes, it's one that has profound implications for the future of filmaking, not least in Australia

Sydney, Mid-October and summer has arrived in a day. By 10am, the skies have stormed and cleared, the bitumen steaming, the air drinkable. Not that you’d know to look at George Miller, a woollen scarf around his neck, tucked into a huge leather bomber jacket as he slumps in a chair at his Dr D Studios in Sydney’s CarriageWorks.

Gone is the trademark chilli shirt, adopted years back because it meant one thing less to decide each day. It’s four years since his last major roll of the dice, the penguin musical Happy Feet, which took out the Oscar and confirmed him at the pinnacle of his profession; six weeks before its sequel Happy Feet Two, opens in the US as Warner Bros tent-pole hope for the Thanksgiving weekend.

Miller has been the prototype of all his blue-eyed heroes, from Mad Max to the penguin Mumble, his landscapes always interior. “It’s almost embarrassing,” he says. “I live way too much in my head.”

Right now he is dressed for Antarctica. Or one last aerial raid. “At this point you’re always on a war footing,” he says. “When I made my first film, Mad Max, I was constantly bewildered, it felt so chaotic. I remember Peter Weir telling me a film was like a battle zone, and it’s true: you have to be alert, resilient, prepared for anything. There are lots of stumbling blocks along the way, but you have to prevail.”

Around him, out in the cavernous halls of what he calls ‘Penguin Prison’ (“but I’ll be on parole soon” ), geeks sit in the gloom adding feathers to bird carcases onscreen. They are the survivors of a workforce that peaked mid-August at 670. Pretty soon, however, even the stragglers will be gone. Some will be picked off by the the talent scouts who have already flown in from the northern hemisphere, while their handiwork flies north to lift (or not) the Warner Bros big top on a crucial US weekend.

The rest, the 50 or 60 on the longer-term contracts, will be made redundant within weeks. It’s the latest setback in a story that dates back to when George Miller last spoke to The Australian Financial Review Magazine in 2007. Back then, Miller deplored the creative brain drain under way, not least the computer-generated-imagery (CGI) talent he helped develop on Happy Feet, then watched disappear offshore to work on other international projects.

In the intervening years a director who has always kept Hollywood at arm’s length has done something about it, opening Dr D three years ago with his partner, Doug Mitchell, and Omnilab Media Group, to handle Happy Feet Two, their next project, Mad Max 4: Fury Road, and other animated-feature projects down the line. Even with most of the staff gone in mid-October, it’s a true Tardis of an operation. Outside the punters stream past from the Saturday growers market, eyes down as they navigate the puddles, oblivious to the dream factory lurking behind Dr D’s heritage facade.

Inside it’s day for night. Old rail carriages have been repurposed as offices. A single frame of a dancing penguin is frozen onscreen in the empty in-house cinema. The place is so big it requires its own generator, the sheer number of departments you pass through – art, animation, surfacing, stereo (3D), digital-crowd – an indication of the complexity of a project in the final fortnight of an extraordinary two-year production. In the middle of the main warehouse, the now deserted motion-capture stage faces what is effectively the bridge of this ship: a suite of demountables that serve as HQ for Miller and Mitchell, though they prefer to be interviewed in the ‘Fury Road meeting room’, a roofless cubby at one end of the hall, lidded in blackout fabric so it cannot be seen – worse, photographed – from the walkways above.

That is because their next Warner Bros-funded adventure, the most anticipated film of Miller’s career and the one he has fought longest and hardest to make – the one, too, on which this particular dream palace is about to founder, it transpires – is storyboarded around the walls in hand-drawn cells.

The Fury Road room is actually more a cubby within a cubby, given Dr D itself is just the largest and latest of the playhouses Miller has been building all his life, from Mad Max 2’s desert outpost to Beyond Thunderdome’s Bartertown, or the forts and tree houses that he and his brothers built as part of what he calls “an invisible apprenticeship in play” in Chinchilla on the edge of Queensland’s Darling Downs.

Problem is, this particular version was conceived in the good old days – pre-GFC, before a levitating Australian dollar and unseasonal rains in the NSW outback – as Miller’s answer to the mini-Hollywood Peter Jackson had conjured across the ditch in New Zealand, which has pumped out everything from James Cameron’s Avatar to his Hobbit films and Steven Spielberg and Jackson’s new blockbuster Tintin.

Dr D’s original ambitious scale was premised on handling at least a couple of major projects simultaneously. And, as anyone who’s cast an eye in the direction of the Australian film industry lately knows, that premise no longer pertains. The dollar’s impact on big-budget foreign-film production in Australia was confirmed by the annual production report Screen Australia issued in October, with no major foreign films shooting here for the first time in decades and even local features down almost 70 per cent in the last financial year to $88 million, from $400 million two years ago.

But even that isn’t Dr D’s essential problem. The studio was established to handle Miller’s creative projects. The workflow issue it faces is his rather than the broader industry’s. Fury Road was to shoot in Broken Hill in September last year, then April 2011, but heavy rain had turned the desert into a flower garden and the water table stubbornly refused to drop. The film will now shoot in Namibia from April (see box, p.32) with additional filming and post-production back in Australia. With Happy Feet Two poised to finish production when we speak, Dr D faces a reckoning familiar to boa constrictors: without decent-sized prey in view, it is about to shrink much as it grew, on the films it swallowed.

Not only is Max not ready, those headaches have “diluted” Miller and Mitchell’s “creative overview of other animated projects”, Doug Mitchell says, including what Miller refers to as “the most ambitious thing we’ve done”, a new animated bear film, Fur Brigade. That has meant a rethink of the Omnilab joint venture. Not that Miller’s latest and greatest cubby will necessarily cease to exist. At the time of writing, Miller and Mitchell were keen to continue on their own account with some restructured version – possibly renamed ‘Dr G’. And they could see a critical mass of work going begging that would sustain it between major films.

Mitchell is the latest in Miller’s long line of fraternal collaborators, from his actual twin John and brother Bill – his co-producer on everything from the Babe films to Happy Feet – to the late Byron Kennedy, with whom he founded Kennedy Miller in 1973. An accountant by training, Mitchell joined Kennedy Miller nearly three decades ago, becoming so central to its fortunes that it was renamed Kennedy Miller Mitchell four years ago. “It’s definitely part of the twin thing,” Miller says. “We’re brothers in arms.”

Six months prior the pair embarked on a concerted, behind-the-scenes campaign to persuade the federal government to extend the 40 per cent Australian producer tax rebate introduced in 2007, which has significantly mitigated the impact of the foreign production downturn by allowing star Australian directors such as Miller, Baz Luhrmann (The Great Gatsby) and Alex Proyas (Paradise Lost) to bring big-budget, foreign-studio-funded projects to Australia. So much so that Screen Australia estimates production will almost return to 2009’s $350 million, when the likes of Gatsby and Paradise Lost are counted.

Miller and Mitchell want that offset extended to cover what are still quaintly referred to as video games. But if that sounds minor, it’s not. Because by video games they mean the whole interactive entertainment industry, which they suspect may yet prove the salvation of not only Dr D, but Australia in the fast-converging game of 21st century storytelling.

It’s a punchline Miller has been working towards for years. When he spoke to the Financial Review Magazine four years ago, he had just joined Hollywood's biggest agency, Creative Artists, for some heavy Hollywood help in understanding the way “the storytelling of games and the storytelling of cinema [were] converging”. Since then, “what everyone predicted would happen has happened,” he says. “This fantastic convergence, but to an astonishing degree, and much more rapidly than people had imagined.”

Which is why immediate action is required. Filmmaking has reached a tipping point, he says. Distinctions between platforms or genres no longer make sense, with a film’s release windows – cinema, DVD, download, even game – ever shorter stops on a single trajectory. “Multi-platform, that’s the thing,” says Miller. “Create once; publish many times, on multiple platforms. You create a world and then you go in to all the different platforms – your iPhone, your iPad, on the net . . .

“At the same time, animators are moving to live action and vice versa. I tend to conflate digital animation with the game world, but Pixar’s Brad Bird – who did [acclaimed animated features] The Incredibles, Ratatouille – just made [the Tom Cruise live-action film] Mission: Impossible IV, and Andrew Stanton, who did Finding Nemo and WALL-E, has just done his first live-action film, while Spielberg and Jackson have just moved into animation with Tintin. The result is that there are more roads leading in to the intersection, and they’re cross-fertilising much more rapidly than one might have predicted.” (The moment is commemorated within a fortnight of our interview in a Time cover devoted to Spielberg’s 30-year wait for the motion-capture technology to finally allow him to film Hergé’s classic comic strip).

The problem is that, unlike Jackson, Miller and Mitchell don’t have a compliant government to rush through emergency legislation, as the NZ Parliament did last October, amending employment laws to ensure the Hobbit films were made there. Not that federal arts minister Simon Crean, at work on his big, new cultural policy, hasn’t taken them seriously. “Simon’s popped in several times over the last six months,” Mitchell says, including a day spent watching Dr D at work. “And we’ve also had Kevin Tsujihara [president, Warner Bros Home Entertainment] visit Australia and meet Screen Australia. Simon has definitely understood it, and he’s discussing it with the treasury. And they get the point, but given the budget situation, it’s difficult to persuade treasury.”

Film-production incentives need to keep pace to capitalise on what Miller calls “an enormous opportunity for Australia”. As he sees it, potentially exponential shifts lurk in the cross-fertilisation of those previously distinct genres, platforms and formats. TV has long been hailed as the new film, the medium of choice for high-concept, long-form storytelling from The Sopranos to Mad Men. Now games, too, have turned filmic (and vice versa if you look at films like 300).

The examplar is LA Noire, the game developed by Australia’s Team Bondi using MotionScan to capture actors' performances, including hyper-real facial expressions, for New York-based Rockstar Games, home of Grand Theft Auto. Set in the 1940s Los Angeles of LA Confidential, but with multiple digressive story lines, LA Noire became the first video game to premiere at a film festival – Robert De Niro’s Tribeca Film Festival, no less – in April.

The Guardian’s perfect-score review is symptomatic of the fairly stunned reaction: “Ever since it first worked out how to assemble pixels so that they resembled something more recognisable than aliens, the game industry has dreamed of creating one thing above all else – a game that is indisting-uishable from a film, except that you can control the lead character. With LA Noire, it just might, finally, have found the embodiment of that particular holy grail.”

Not that that helped Team Bondi. Like filmmakers, local video-game makers had thrived for a decade while the dollar was low, and were decimated as it rose, Mitchell says, unable to compete with Canada, which offers a 40 per cent rebate for games, and Ireland, which recently introduced similar measures. Team Bondi got into difficulties as LA Noire emerged, as did Brisbane-based Krome, which Mitchell says had offices in Melbourne and Adelaide and employed 400 people at its peak, and was several million dollars into working on the game of Happy Feet Two at the time.

It was Krome’s travails that initially led to the formation of Kennedy Miller Mitchell Interactive, with Krome maintaining its Brisbane office. Since then they’ve “taken the risk and absorbed not only the Krome team but Team Bondi’s last standing warriors,” says Mitchell. “There’s never enough critical mass in this country to keep going,” adds Miller. “What’s fascinating, though, is that Team Bondi immediately went to work on Happy Feet Two. People can move from a game to a movie and be completely at home, because it’s the same skills, process – the same game.”

Which is why, after resisting the impulse for years, and watching imitators clean up, Miller is now finally going to make Mad Max, the game. Backed by Warner Bros, the game version of Fury Road was to be made in Sweden, until Miller saw what Team Bondi could do. He has also acquired the rights to Team Bondi founder Brendan McNamara’s next game, Whore Of The Orient.

“With the government’s support we can immediately go forward with two games,” says Mitchell. “Warner Bros is standing by, willing to do Fury Road; the incentive would bring it back here in a New York minute. It’s not immediately obvious but the potential in the video games sector is massive. Just from the statistics people are showing me, it’s a $60 billion industry fast-tracking towards $90 billion. And it’s not dominated by any particular country. Films are very expensive, so studios . . . are making drastically fewer of them, but much higher quality, and they invest in sequels, because they know that they’ve got an opening which they don’t have to buy with their marketing dollars as aggressively.

“They’ll make 10 films where they used to make 20. So, instead, people are drifting to game acquisition because of the budgets. The cost of a film may be $170 million – twice that to market it – whereas the basic cost of making a game might be 10 per cent of that. Look at LA Noire, they sold about 3 million units in a week, about $US135 million ($130 million) net revenue, off a cost base which was infinitely lower than even your average low-budget film.”

That will inevitably change how films are made. “There are technologies they have to develop in games because things need to happen more quickly in a game,” Miller says. “Those are going to speed up digital filmmaking and television way more, because they’re obliged to do it if they want things to look as real as possible and happen in real time. And that’s really pushing things – so that instead of years to make an animation film, that time could collapse.” Adds Mitchell: “Video games will end up the engines to distil TV episodes, movies, and generally move stuff very quickly in a much more cost-effective way, back out and deliver almost instantly to situations where you’re buying it online.”

But that’s just the business case. Characteristically it is the storytelling possibilities that have really seized Miller’s imagination. His apparently disparate oeuvre, with no film resembling its predecessor, has always been about finding fresh, compelling ways to entice punters into cinemas to watch essentially archetypal heroes’ journeys, from Mad Max and Lorenzo’s Oil to the cutting-edge animatronics that allowed him to film Babe a decade after he read the book; CGI with Happy Feet and now 3D with Happy Feet Two.

Each time, a technological breakthrough enabled a story to be told in a new way, providing a point of difference, a selling point. Games potentially represent the next quantum leap, he says. “It’s four-dimensional storytelling. A game can literally become the equivalent of a novel. That is the thing that people like me who write screenplays envy about novelists: that you can actually stop time and explore little cul de sacs. Whereas in a movie, you’d love to stop and examine that character, but you can’t. You’re on a rail . . . and if you talk to Brendan [McNamara], who is the brilliant mind behind this, it’s all the same issues as film. Instead of writing a 100-page screenplay, he wrote a 2800-page screenplay. But it’s the same dialogue, acting, blocking, wardrobe, costume, lighting, vehicle simulations. It’s a movie that’s played interactively at home.”

Which leaves Miller at yet another interesting juncture. Happy Feet Two won’t materially affect his future: Warner Bros long ago gave Fury Road the green light; indeed the studio has supported its darling through hell and high water – literally. Nor does the old saying that “you’re only as good as your last work” apply as much in the film world. “If you have one success, one conspicuous success, it allows you about three failures before people start to question your efficacy,” Miller says. “I don’t know how Happy Feet Two is going to perform; no one does,” he says.

“But the great attraction of sequels is it gives you a chance to do it better. What makes me quite relaxed at the moment is I know we’ve made a better film than the first one. There’s no question this film is significantly better in virtually every dimension. And that makes me feel, well, at least I’m progressing. It’s incredibly tempting to just phone it in, to say, well, let’s just cash in. That’s absolutely not what drives me.”

So what, at 66, is it that makes him trade Penguin Prison for the Namibian desert and whatever work camp comes next. “Curiosity,” he says. “To work with this new media, it’s like Br’er Rabbit in the briar patch. It’s just so exciting.

“At my age, the saddest thing to me is that I’ve got way more stories than I’ll ever have time to tell. I somehow thought my imagination would plateau. It might mean that I’m in early dementia, but my imagination is way more fervent than it was, and it stands to reason. I’ve been doing this since I was a little kid. My imaginative powers are probably the most muscular part of myself.”